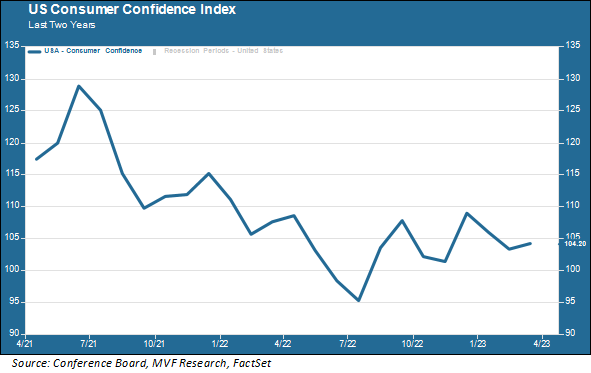

Consumer spending drives the US economy, as the single largest factor influencing gross domestic product. The resilience of the consumer has been the story of the past twelve months, with a demonstrated willingness to accept the higher prices consumer-facing companies have been passing on to offset their own higher input costs for labor and materials. In earnings management calls over the last year, company after company has offered up some version of the following formula: average ticket higher, average transaction count lower. That meant, in essence, that even if demand was weakening, the decline in footfall was compensated by higher prices. Sales continued to grow, and profit margins remained healthy, thanks to consumers’ willingness to put up with the price increases. The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index, a measure of household sentiment about their current and forward-looking financial situation, has held up reasonably well although understandably lower than the stimulus-aided optimism evident in early 2021.

As the Ticket Turns

That consumer confidence readout of 104.2 in March was actually a bit higher than analysts had expected. A reading above 100 tends to be seen as expansionary, so that would seem to be good news. But we are starting to get data coming in from other sources suggesting that actual retail activity is reflecting a change in consumer behavior; in particular, a slowdown in discretionary spending with less willingness to passively accept monthly price increases. In a report that came out yesterday on March sales activity Costco, a bellwether for middle class consumer spending trends, average ticket was down by about 2.7 percent from the previous month – a reversal of recent trends and below expectations. The company also noted a distinct move away from big-ticket discretionary items to lower-margin consumer staples. That fits with a trend we have been seeing elsewhere, and we expect see more of it as the Q2 earnings season gets underway in full starting next week.

JOLTS to the market

A key element of consumer confidence, of course, is the strength of the jobs market. Simply put, the more confident you are about your current job and take-home pay, the more sanguine you are likely to be about your monthly spending plans. As we have noted repeatedly over many months, the US labor market has been strong to a degree that has puzzled many economists, including those at the Fed. Even while noting the many upside surprises, like the blowout 504,000 nonfarm payroll gains in the January report this year, we have also reminded our readers that jobs numbers tend to be a lagging indicator, following rather than leading directional changes in the economy.

This week the market seemed to get caught flat-footed by a data point showing about 500,000 fewer job vacancies in February than economists had been predicting. The JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics seemed to suggest that the labor market’s ability to defy gravity after a year of Fed rate hikes might be coming to an end. Or not, one could argue, because it’s just one number. But the next day another labor market report – the ADP Employment Survey – also came in well below expectations. And today we saw a higher than expected number of initial claims for unemployment insurance. So now it’s not just one number but three, in the space of three days.

Bonds Bet on Burns

What does all this mean for the market? The short term, as we always say, is unknowable. That said, we continue to shake our heads in wonder at the bond market’s seemingly unshakeable conviction that Fed rate cuts are just around the corner. Yields on 10-year Treasuries are now below 3.3 percent, and the entire yield curve remains below the upper boundary of the Fed funds target rate – with at least one more Fed funds rate increase likely when the Fed next meets in early May. The bond market seems to be betting on Jay Powell channeling his inner Arthur Burns – the Fed chair during the tumultuous middle years of the 1970s whose constant zigging and zagging back and forth between fighting inflation and staving off recession accomplished neither and cost the Fed dearly in credibility. But Powell is not Arthur Burns and we continue to believe that the market’s pricing in of rate cuts in the second half of this year is a fool’s errand. We may be wrong. And it will be increasingly hard for the Fed to navigate its monetary policy if the signs of a consumer-led downturn continue to build up – particularly now with the attendant concerns about a credit crunch in the banking sector. But we don’t think those rate cuts are coming until inflation is on a clear and directionally robust path downward. That, as we see it, is yet to happen.