One year ago – April 23, 2020 – the world was coming to terms in fits and starts with the reality that the pandemic wrought by the Sars2-Cov19 virus was going to be more than a couple weeks of absence from the office and social distancing from friends and family. But while medical experts and laypeople alike struggled to comprehend what this virus was all about, as they studied genetic sequences and hoarded sanitizer and paper products, the stock market had already figured it all out. On April 23, 2020 the S&P 500 closed at 2794, up about 25 percent from the low point of exactly one month earlier on March 23.

Fully Baked Good News

The market’s carefree optimism was out of step with the general mood of the rest of the world, but there was at least a coherent argument for the bulls to make. Even at that early stage of the pandemic there was already evidence that a vaccine might be closer at hand than had been the case in earlier pandemics. The bull market case in its essence was that of all the possible outcomes that could emerge from this health crisis, the best possible one would prevail. The key to that best possible case was the vaccine. Get the masses of the world inoculated against the disease and the world goes back to normal.

In the immediate days following the US presidential election in November, first Pfizer and then Moderna announced the successful Phase 3 trials of their respective Covid-19 vaccines. The bulls had been justified. The S&P 500, which had stalled out through most of the fall to date, resumed its upward ways. The period from November 2, 2020 to April 22, 2021 saw another 25 percent gain.

Not So Fast

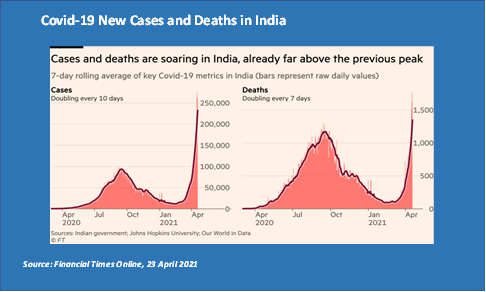

In a sense, though, the market has been trading on forward assumptions for the entire duration of the pandemic up to and including the present day. With that in mind we introduce some sobering data from India, where the pandemic is in the early stages of a new and very dangerous wave.

The above chart shows the seven-day rolling average of new cases and deaths. In just the last two days, Thursday and Friday of this week, the number of new cases was 315,000 and 330,000 respectively – the highest number of single-day new cases registered anywhere in the world up to now (the previous record was set here in the US back in January, at around 310,000 cases).

What is happening in India is playing out elsewhere in the developing world, including Latin America, Asia-Pacific and Eastern Europe. The health care systems in these countries are at risk of being completely overwhelmed. In India, supplies of oxygen are running out at hospitals across the country, with caregivers worried that this will lead to an even greater spike in deaths. Vaccine distribution in many of these countries is haphazard and often not available at all. Most alarmingly for the rest of the world, the rapid transmission is leading to a proliferation of variants, including the B.1.617 variant that is central to India’s recent surge and which health experts are studying closely to understand its transmission and possible vaccine evasion properties.

Simple Model, Complex World

The current setbacks to pandemic progress in India and elsewhere underscore the limits and risks in simple stock market narratives. The best-case narrative factoring into today’s price levels makes some simple assumptions; namely, that a vaccine will beat back the pandemic, consumer demand will quickly return (and indeed will outpace historical growth trends for at least awhile) and the entire unfortunate experience of 2020 and early 2021 will be a distant memory in short order. S&P 500 corporate earnings are expected to grow by 30 percent this year, largely premised on a near-seamless return of demand and no major hiccups in the production and distribution chains supplying goods and services.

But the real world is more complex than any model can accommodate. We don’t know all the potential risks that may emerge from the prolongation of the pandemic in emerging markets. We do know that there is quite a bit of investor capital in these markets. In the first quarter of this year investors purchased $191 billion worth of emerging market debt, much of which is denominated in developed-market currencies like the dollar, the euro and the yen. A prolonged period of economic difficulty for these markets could spell big trouble for fixed income investors. The Indian rupee, for example, has fallen about four percent since this recent pandemic wave began.

It’s fair to say that, on balance, progress towards ending the pandemic is positive. But there are caveats to the positive assessment, and emergent risks to any of the assumptions in the bullish narrative. With all the good news that is already baked into the equation, it would not surprise us to see a bit of a pause in growth. Not a major reversal (although that can never be ruled out). But a pause of sorts would not be an unreasonable scenario in the coming weeks.