The Consumer Price Index (CPI) report that came out on Wednesday this week was a doozy. Headline inflation by the CPI measure was 6.2 percent, the highest level since October 1990. Core inflation, which excludes the volatile categories of food and energy, was 4.6 percent, higher than at any time since 1991. The CPI report came on the heels of a producer prices report from China showing that price increases at the wholesale level – often called the “factory gate” inflation measure, was also at the decades-high level of 13.5 percent. The China number suggests that pressure on downstream businesses – distributors and retails – to pass on price increases will continue at least for a few more months.

Purchasing Power Paradox

The normal effect of inflation on bond yields is to send them higher. People traditionally have bought bonds for the stability of a reliable stream of income. Embedded into the expectations of nominal bond yields is that they will protect purchasing power against inflation – so when inflation rises, bond yields will also rise as investors demand more compensation for holding the securities. Think of it this way: if you think the income from your bond investment is going to be worth less a year from now than it is today, then rationally you would prefer to spend the money today rather than defer it to the future. Collective decisions along these lines will then naturally send bond prices lower, and thus yields higher.

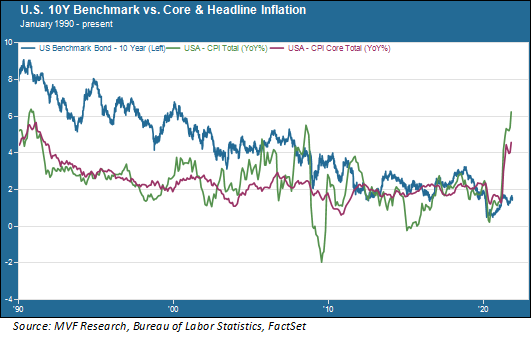

But that is not what is happening today. Consider the chart below, which shows the nominal 10-year Treasury bond yield compared to headline and core inflation since the beginning of 1990.

As you can see, for most of this period the 10-year yield traded well above inflation, narrowing in recent years but still mostly positive. For much of the past decade core inflation (the less volatile measure) hovered around the Fed’s target of two percent while the 10-year Treasury yield stayed just above that.

Keep Calm and Carry On…

When inflation started to rise earlier this year bond yields initially followed suit. But the Treasury market stabilized after reaching highs just shy of 1.8 percent back in March, and currently trades in a range between around 1.6 percent and 1.4 percent. This has puzzled fixed income traders, many of whom had placed significant bets on rates rising. Is it because the bond market believes the Fed? For the entirety of this year Fed chair Jay Powell has taken every opportunity at his disposal to wave away threats of inflation sticking around for more than a transitory period. This too, will pass, says Powell in his best imitation of a doting grandmother offering comfort drawn from her extensive life lessons.

There is still a cogent argument to be made in favor of transitory-ness. There have been two major inflationary periods in postwar US economic history: the period immediately after the war (mid-late 1940s) and the long stagflation era of the 1970s. Many economists argue that the current environment looks more like that of the late ‘40s. Back then, consumer demand shot up as households went out to buy all the things they had sacrificed during the war years, while at the same time the companies supplying goods had to retool their operations from military to civilian purposes. This inflation was brief; indeed, after topping out in early 1948 prices fell sharply and even experienced a brief period of deflation.

That may well be a more accurate model for today’s environment. The supply chain problems may also be exacerbated by the fact that consumers are buying more goods than services today, as compared to the prevailing trends of recent history (hence, more pressure on the transportation of goods from point of origin to point of sale). Services such as restaurants, personal care & beauty and retail, while certainly up from their peak-pandemic lows, are still struggling with the persistence of Covid and related social distancing restrictions. The attendant widely reported labor shortage may also have a sell-by date if people in their 20s and 30s come to the conclusion that they will still have to earn a paycheck for a while longer before they are able to retire.

…Or Don’t

Fed chair Powell may be right in the end about inflation – but he could just as easily be wrong. If the key trends driving inflation today – the supply chain issues along with shortages in both the labor market and in key energy sources like oil and natural gas – persist well beyond the 3-6 month time horizon the optimists say is the outer limit, then even subsiding levels of demand may not bring us back to the kind of 1.5 – 2 percent inflation world that would make current intermediate-long term bond prices look rational. In fact, if consumer spending subsides then we could well be looking at a world closer to the 1970s than the late 1940s – high structural inflation with attendant low growth – in other words, stagflation. This is a world where no amount of prestidigitation by the central bank in flooding asset markets with newly-printed money will do any good. Bond yields would most likely adjust accordingly and all the sybaritic pleasures of today’s stock market – the memes, the pockets of absurd valuations, the “this time it’s different” pronouncements – lose their luster. 1999 didn’t last forever, either.

Inflation is arguably (by which we mean “in our opinion”) the most important of all the issues out there in the daily conversation. As it goes thus, sooner or later, goes the bond market and thence the stock market. We are fond of saying that if you want to know what’s going on in your stock portfolio, watch what’s going on in bonds – never more so than in a world of six percent inflation and 1.5 percent nominal bond yields.