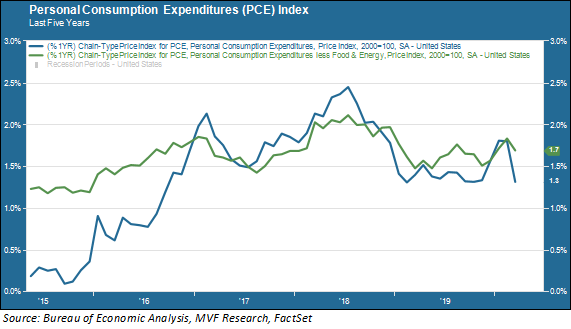

We have become accustomed in the past few weeks to festooning these weekly commentaries with “never before in history” charts: the latest employment numbers, or investment grade bond prices or some other eye-popping deviation from long-term norms. We could do the same this week – headline retail sales plummeted by more than 16 percent in April, for example. Instead, we’re going to spend some time talking about the one major macro number that hasn’t changed much in the time of the coronavirus pandemic. Inflation, for the moment, continues doing what it has been doing for much of the past decade – in other words, not much at all. Below is the Personal Consumption Expenditures index for the past five years. The PCE is the Fed’s go-to inflation number; the one it targets for a sustained rate of two percent.

The Two Percent World

The Fed, along with most followers of inflationary trends, focuses on the core PCE number (shown in green on the above chart) because it excludes the more volatile categories of food and energy products. You can see in the chart that the so-called headline number (in blue) bounces around a lot more than the core figure, much of which has to do with the volatility in commodity prices ranging from crude oil to natural gas, from soybeans to wheat.

In any case, core PCE has been fairly docile in recent years, only rarely even attaining that two percent Fed target. It certainly bears no resemblance to the wild inflation spikes of the 1970s, nor to the deflation that was an unpleasant feature of the Great Depression in the early 1930s. Call it “no-flation” perhaps. Until the pandemic hit, many economists argued that “no-flation,” with the PCE ambling along a bit shy of its two percent target, may be the natural state of things in a globalized, technology-advanced world. That assumption is now in question. What experts can’t seem to agree on, though, is whether we go from no-flation to lots of inflation – or the scarier scenario of deflation. Or neither.

Money, Money Everywhere

A quick look at the numbers suggests that not many people see the looming specter of inflation any time in the near future. Five year US inflation swap rates, which provide a window into what traders think inflation will be five years into the future, are currently around 1.7 percent, and they haven’t been above 2.5 percent any time in the past couple years. TIPS – Treasury Inflation Protected Securities – are not trading notably better or worse than their nominal Treasury peers.

But a plausible inflationary scenario does exist. Inflation happens when more money chases fewer goods. And if there is one thing the global economy has a ton of today – thanks to the energetic efforts of central banks around the world – it’s money. The Fed has spent more money on bond purchases since the start of the crisis than it did throughout the duration of its second and third quantitative easing programs in the last decade.

Now, the idea is that all this emergency money is supposed to go away once the pandemic is over. But the experience of the last crisis, in 2008, demonstrates how hard that is to achieve in real life. Asset markets get jittery every time they think the Fed is going to take the punch bowl away. Investors who are confident that the punch bowl will always come back full have a pretty solid batting average to date.

An inflationary spike could happen if, while the Fed is still creating money, demand for goods and services outpaces supply. The seamless continuation of existing global supply chains is by no means a given. Moreover, if those optimized supply chains migrate to higher-wage environments (e.g. with more links leaving emerging economies for the US and Europe) then factor costs will likely trend up as well. Normally, such a scenario would lead the Fed to raise interest rates to keep prices under control. But the Fed would be reluctant to do that, not just for fear of another market tantrum like the last time they tried to raise rates in late 2018, but also because the cost of government debt would skyrocket, potentially while Treasury is still issuing lots of it for its relief programs. Boom – just like that it’s 1973 all over again.

Tired Old World

That inflationary scenario does sound unpleasant, but it would still be preferable to another potential outcome – deflation. Ask an economist what the difference is between a recession and a depression and she will tell you the 3-Ds: Depth, Duration and Deflation. We know the current downturn is going to have depth, given where employment numbers are now and where Q2 GDP is very likely to be when we get that reading in July. Hopefully we will avoid the years-long duration of the misery that followed the stock market crash in 1929.

We also would not want to see the crash in consumer prices and wages that was characteristic of the Great Depression. Deflation is a by-product of low consumer demand – potentially following a downward spiral in wages caused by widespread unemployment. It is terrible for those in debt – households, businesses and public institutions alike – that have to pay fixed obligations with money that is worth less. These outcomes have the effect of dampening new business investment, which in turn facilitates a self-fulfilling negative cycle.

The closest we have come to a deflationary scenario in modern times is Japan, which has been fighting punishingly hard demographic trends for more than 30 years. The Bank of Japan has engaged in massive amounts of monetary stimulus over this period, yet nominal prices have never gotten onto a normal trend. The BoJ even purchases Japanese common stock outright – yet the Nikkei 225 stock index has never recovered more than 63 percent of its previous record high in 1989. Yes, 1989.

Deflation could happen if that second of the 3-Ds – duration – turns out to be much longer than expected; for example, if estimates of a vaccine in 12-18 months prove unrealistic and more businesses are allowed to go out of businesses with no additional relief from the public sector. Fed chair Powell hinted at this threat in remarks made this week about temporary features of the current downturn becoming more permanent if more is not provided in the way of support. Additionally, some economists see Japan’s demographic challenges of an aging and increasingly unproductive society as a model for what lies down the line for Europe and eventually the US.

We do not share that rather bleak outlook and do not believe that chronic deflation is a high-probability outcome from this crisis. While there are still many uncertain variables at play, given what we know today plus some best-guess assumptions about vaccine development and other critical factors, we would see a return to the “no-flation” of the recent past as likelier than either a 1970s-style inflationary environment or a deflation-produced depression. But we need to be alert to any warning signs that would suggest otherwise.