Jackson Hole, Wyoming is by all accounts a lovely place to be in late August, with crisp late-summer skies of azure framing the inspiring cathedral spires of the Grand Tetons. Central bankers from around the world gather in this idyllic venue every year around this time for their annual confab on monetary policy. More than a few recent out-of-the box inspirations for fixing the world economy have proceeded from the clarity of mind a vigorous hike in the hills affords.

Zooming In On Inflation

Sadly for the monetary denizens of Washington DC, Frankfurt, Beijing, London, Tokyo and elsewhere, their 2020 get-together wound up suffering the same fate most of us have put up with since March, with the pleasures of tactile in-person experiences replaced by the ubiquitous rectangular screens and intermittent audio-visual freeze-outs of teleconferencing. Despite this, at least one proposed policy change came through the Zoom box that may have a meaningful impact on the economy and in particular your fixed income portfolio in the months to come. Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced that, going forward, the Fed will be using their long-standing two percent inflation benchmark as an average target. This means that inflation would be permitted to trend above two percent for a sustained period – a sort of “make-up” for all the months it has trailed the benchmark. While that may not sound like much it has profound implications, some of which have been quietly bubbling up in recent weeks in bond and currency markets as traders started placing bets on the likelihood of the Fed’s altering course.

Rising Spreads and Weak Dollar

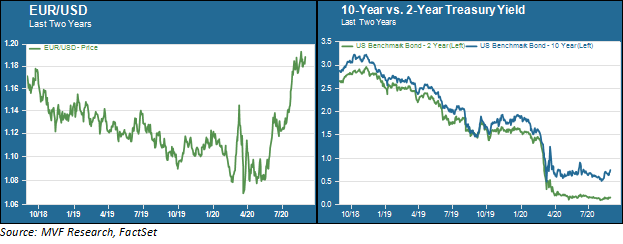

The chart below shows two of these recent market moves. The dollar has been trending weaker against other currencies (shown here versus the euro, where an upward trend represents a stronger euro), and intermediate Treasury spreads are widening.

Now, there are a variety of factors at play here, not all of which can be attributed to anticipation of the Fed’s move. But the strength of foreign currencies versus the dollar and the widening of longer-term interest rates versus shorter-term ones both speak to the anticipated effects of inflation. All else being equal, a higher rate of inflation makes assets denominated in the inflated currency less attractive to hold. And yields on securities bearing fixed coupon payments will tend to rise as investors demand compensation for the expected loss of purchasing power they will experience as inflation eats into their nominal coupons. That will have a more pronounced effect on bonds with longer maturities. As long as the Fed keeps the Fed funds rate effectively at zero, yields on short-term bonds — which are effectively anchored to monetary policy — will stay low. Longer-dated yields, though, will rise.

If you believe the Fed can achieve what it is setting out to do – and those recent trends in the dollar and yield spreads suggest that many in those asset markets buy into the likelihood of it coming to pass – then a logical portfolio move would be to reduce exposures in intermediate and long-term Treasuries and to take on some exposure to non-dollar denominated assets like developed or emerging market equities. But there is no guarantee that this will happen. In fact we see three potential alternative outcomes, which we will set out below.

Goldilocks, Too Cold or Too Hot?

Let’s call the Fed’s target outcome the Goldilocks scenario, because economists and market pundits love that metaphor to death. This is where the Fed sets inflationary expectations a little higher than two percent – say somewhere around 2.25 – 2.5 percent, and consumer prices adjust accordingly. In this scenario the Fed can keep short-term interest rates down at their near-zero levels (maybe even putting explicit target caps on maturities out to 2 years) while letting spreads widen on longer-dated bonds. As you can see from the chart above, yields on the 10-year remain not far off their 2 year lows even after advancing in the last couple weeks. In fact those lows are historic lows, as in “entire history of 10-year bonds” low. Say the 10-year yield drifted back up to the mid-twos or even three percent? That by itself would not present much of a problem for an economy chugging along at a nice post-pandemic growth rate (which is precisely what that somewhat higher rate of inflation would imply).

What could stand in the way of that Goldilocks scenario? Well, for one thing, all the monetary stimulus the Fed poured into the economy after the last crisis, in 2008, failed to move the inflation needle even to two percent, let alone beyond that level. During this period the S&P 500 grew by leaps and bounds, but the economy itself limped along at a rate of growth well below the trend levels of previous cycles. Household earnings likewise stagnated for most income levels apart from the very highest ones. It may well be the case that, in the absence of any kind of meaningful economic realignment that encompasses a wider swath of households, things just keep on limping along as before, with GDP growth near or below two percent and an absence of the kind of pressure that would result in higher consumer prices. Interest rates across the board would stay at near-zero levels or even fall into negative territory, risk assets like stocks would mostly keep growing and the dollar would rise or fall based on how other parts of the world were dealing with things. It would be like 2017 all the time. That’s the “too cold” scenario.

Where things would really start to go off the rails, though, would be in the “too hot” case seeing the light of day. This is where all those trillions of dollars Congress and the Fed unleashed into the economy back in March (taking the US national debt level to more than 100 percent of GDP), together with still-disrupted business supply chains (possibly more expensive supply chains in an environment of de-globalization) combine to create that textbook definition of inflation – more dollars chasing fewer goods with higher input costs. Inflation doesn’t just settle benignly into a 2.25 – 2.5 percent range but maybe jumps into mid-single digit territory.

In this scenario the Fed’s easy money policy goes out the window and the whole house of cards propping up global asset markets comes tumbling down. The 40-year bull market in bonds goes into sharp reversal and equity markets experience something like the 1970s – punctuated by periodic bear markets but mostly just stagnating and producing little for investors outside of dividend payments. This scenario, in our opinion, is the one that poses the biggest risk for portfolio strategies premised on the belief that what has worked for the last decade (low domestic growth, mostly healthy corporate earnings and a permanent Fed tailwind) will work forever.

We do not think the “too hot” scenario is the most likely outcome; in fact, we think either the Goldilocks or the “too cold” alternatives both make a more compelling case in light of where the world is today. But we cannot simply wave it away, either – to do so would not be faithful to our commitment to protect the downside while seeking growth opportunities. We will continue to closely observe the market’s reaction to the Fed’s new policy and the economic developments that will give us more clues in the coming weeks and months about how it might play out.