We wrap up our mid-year review of recent asset price trends with a look at non-US equities. This is a topic on which we periodically get some pushback, notably for the fact that we have been very underweight these asset classes (international developed and emerging markets equities) for quite some time now. After all, the foundational rule of modern portfolio theory as originally put forth by Harry Markowitz back in his 1952 paper on portfolio selection is diversification – distinct asset classes that do different things at different times (i.e., low correlation with other assets in the portfolio) so as to optimize risk-adjusted return over time.

A Long Way from 1952

All of that makes sense, and for that reason we did not simply waltz out of larger weights in international equities on a whim. We conducted a lot of analysis, asked ourselves the same questions over and over, and concluded that, at least for the time being, we do not see an overriding strategic benefit to these asset classes as a substantial portion of our portfolios. The world has changed since 1952 in many ways, not least of all in the closer interrelationships between the countries that make up the global economy. Markowitz’s core insights have yet to be challenged seriously by a competing theory of long-term portfolio management – but there is a case to make that the diversification benefits of non-US equities are quite a bit weaker today than they were in decades past.

The Problem With Tactics

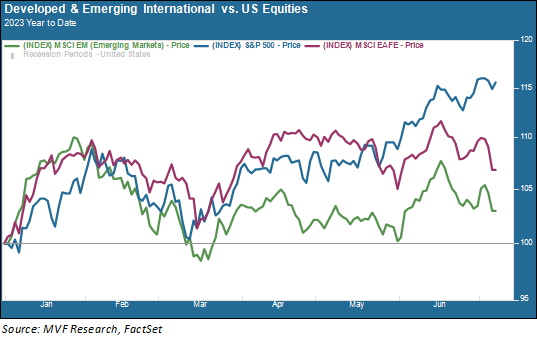

Non-US equities have certainly had periods of outperformance, including – for a very brief while – earlier this year. The chart below shows the relative performance of the S&P 500, the MSCI EAFE index of developed international equities, and the MSCI Emerging Markets index since the beginning of 2023.

For most of January, in fact, both emerging and developed international equities (the green and crimson trendlines, respectively) outperformed the S&P 500 (blue trendline). As the second quarter wound on, though, the familiar pattern of US outperformance returned. Note that in this chart we are showing returns in terms of US dollars, because what matters for a US-based client is not only how any foreign asset performs on its own terms, but how that translates back to US dollars. Much of the excitement at the beginning of the year, indeed, had to do with the US dollar losing some of its recent strength against the euro and a few key emerging markets currencies.

This highlights one of the pitfalls of making tactical (as opposed to strategic) positioning moves for non-US assets. Short-term currency movements are notoriously fickle. Even if you get it right going in, it’s next to impossible to figure out when the favorable currency position reverses is going to reverse. Currently, for example, the euro is still holding its own with a slight gain against the dollar for the year to date, but both the Japanese yen and the Chinese renminbi have fallen by high single digits against the dollar.

No Long-Term Advantage

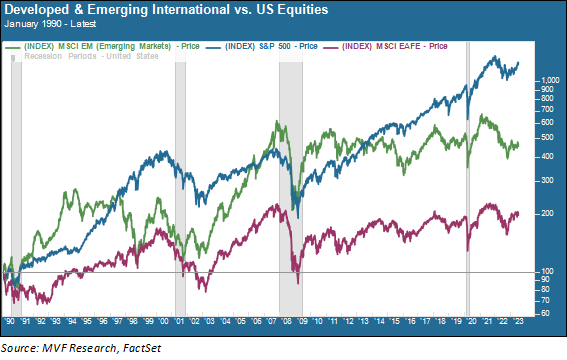

To go back to our earlier discussion about long-term portfolio construction, the strategic case for non-US equities comes up short here as well. Here below is the same chart as the one we just showed you, except that now the time period is not just a brief half-year, but a multi-cycle run of more than thirty years.

Different time period, same outcome. Since the beginning of 1990 (the start date for this chart) the S&P 500 has outperformed the MSCI Emerging Markets index by a magnitude of more than double, while that magnitude is more than five times for developed international equities as represented by EAFE.

And this doesn’t even tell the whole story. That 1952 paper on portfolio selection by Harry Markowitz that launched modern portfolio theory looks at risk-adjusted return; in other words, taking into account not just the return itself but how much volatility is associated with the return. Here things work even more against non-US equities. The average standard deviation, a basic measure of asset volatility, for the S&P 500 over the period shown about was around 14.5 percent, while for developed international it was more than 16 percent and for emerging markets around 23 percent. Less return for more risk is the opposite of what a Markowitz-efficient portfolio is supposed to achieve.

We will have more to say about this subject in a forthcoming research paper that will go into the strategic elements at a more in-depth level than here. For now, though, we will simply note that we are satisfied to have not bought into the effusive chatter at the beginning of this year about it being “the right time” to get back into international. There may be a time when it does make sense (more about that in our forthcoming research paper) – but that time, in our opinion, is not today.