Every year, for one week in August, our eyes turn to the great state of Wyoming and the delightful resort of Jackson Hole. There, the great and the good from the world’s major central banks gather to hash out the issues of the day and chart a course for monetary policy in the years ahead. The Jackson Hole meetings come at a particularly poignant time this year, because there is a great deal going on in securities markets and the economy at large. We don’t expect there will be much time for the bankers to enjoy the recreational offerings on hand, but at least they will have the spectacular views of the Grand Tetons for inspiration while they try and figure out how to stick the landing on beating back inflation while avoiding a protracted global recession.

Growth and the Great Repricing

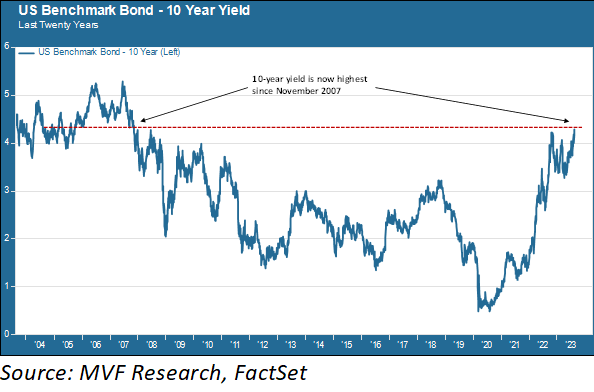

It took more than a year, but it finally seems to have sunk into the collective brain of the investor class that “higher for longer” – the mantra the Fed has been repeating all this time – is actual policy. Fed chair Powell, whose keynote address next week will be the main draw for Jackson Hole proceedings, is unlikely to spell out what the FOMC is likely to do when it meets next in September. But he may give some hints as to how the Fed is digesting a string of economic reports suggesting that the economy is doing better than just about anyone had expected earlier this year. The rosier outlook is making itself felt in the bond market, where the nominal 10-year Treasury yield is now at levels last seen in 2007.

Here’s where this gets complicated. For more than a year now, the Treasury yield curve has been inverted, with short-term rates well above intermediate- and long-term rates. An inverted yield curve is normally a reflection of an expected recession – a theme we have discussed on many occasions this year. Now, however, it appears much less likely that a recession is in the cards for 2023, or possibly at all. That, of course, would be good news for American households and businesses. For the bond market though – not to mention the stock market, which is also directly impacted by interest rates – the news is a bit more mixed. A stronger economy implies fewer job losses, which gives the Fed more room to contemplate its interest rate moves without worrying about the potential effects on the labor market (remember that the Fed has a dual mandate to maintain stable prices and promote maximal employment). That lends more weight to the “higher for longer” policy, which is probably why the expectation of short-term rates not coming down below five percent any time soon seems to finally be conventional bond market wisdom.

But what does that imply for the near-term direction of intermediate and long-term rates? If (a) there is a low likelihood of recession and (b) short-term rates are going to stay anchored in the low-mid five percent range, are we potentially looking at the 10-year creeping back up over five percent or even higher? It’s not an impossible scenario. In the second half of the 1990s, a period of strong real GDP growth and low inflation, 10-year nominal yields fluctuated between six and seven percent for much of the time. The past fifteen years of abnormally low rates notwithstanding, there’s nothing to say it couldn’t happen again.

Curb Your Enthusiasm

That being said, we do not think a return to 1990s-era intermediate rates is a likely near-term scenario, nor do we think that the absence of a recession, if we are lucky enough to avoid one, means a return to ‘90s-era strong growth. In a report published this week, the San Francisco Fed projected that the excess household savings accumulated during the pandemic is likely to be fully played out by the end of the third quarter (which is just a month and a half away). This dynamic is something we focused on in our annual outlook way back in January as a key data point suggesting a slowdown. While we have been pleasantly surprised by the better-than-expected trends in consumer spending and business investment since then, we still expect that the drawdown in savings, along with persistently high levels of consumer debt, will act as constraints on growth levels.

The much-hoped for “soft landing” at the end of the Fed’s monetary tightening, as we interpret it, means sub-two percent real GDP growth, a modest level of payroll gains and a likewise-modest level of wage growth (it also should mean that inflation continues its slow retreat back towards pre-2021 levels). In the very near term we could see intermediate rates rising a bit further, particularly if we get a strong Q3 GDP report as some economists are now forecasting, along with a couple more months of strong jobs reports. But we also expect conditions to settle into the slower-growth phase as the end of the year approaches, which should take some pressure off rates. That’s our view, anyway – we’ll see what Jay Powell and his fellow central bankers have to say about it next week in Wyoming.