The heady cocktail of animal spirits and hope that is the so-called reflation-infrastructure trade has many fans, but perhaps none more so than the monetary policymaking committee of the Bank of Japan. One of the first casualties of last year’s big November rally was the yen, which plummeted in value against the US dollar. That plunge was just fine, thank you very much, in the mindset of Marunouchi mandarins. A weak yen would make Japanese exports more competitive, while the continuation of easy money and asset purchases at home would finally create the conditions necessary for reaching that long-elusive 2 percent inflation target.

Lo and behold, the latest price data show that Japan’s core inflation rate rose 0.1 percent year-on-year in January, the first positive reading in two years. Only 1.9 percent more to go! Expectations of stimulus-led growth, continued weakness in the yen and a return to brisker demand both at home and in key export markets have led Morgan Stanley’s global research team to name Japan as the stock market with the most attractive prospects for 2017.

Patience Has Its Limits

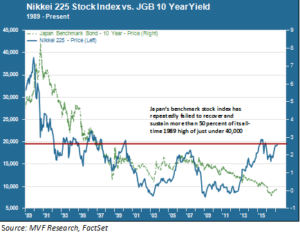

Beleaguered long-term investors in Japan’s stock market would be more than happy to see Morgan Stanley’s prognostications come true – but they have heard this siren song before. The Nikkei 225 stock index reached a record high of just under 40,000 on the last trading day of 1989. As the chart below shows, things have been pretty bleak since those halcyon bubble days when the three square miles of Tokyo’s Imperial Palace were valued by some measures as more expensive than the entire state of California.

If the Morgan spivs are right about Japanese shares, and keep being right, it will represent a decisive break from a struggle of more than two decades for the Nikkei to sustain a level greater than 50 percent of that all-time high value. Prior to 2015, the Nikkei had failed to even touch that 20,000 halfway point at any time since March 2000 (which, as you will recall, was when the US NASDAQ breached 5,000 just before the bursting of the tech bubble). 2015 represented the high water mark of investor expectations for “Abenomics” – the three-pronged economic recovery program of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – to deliver on its promises of sustained growth. Those expectations stalled out as the macro data releases kept pointing to more of the same – tepid or negative growth and the failure of needed structural reforms to take root. Japan’s problems, as anyone who has studied the long-term performance of the one-time Wunderkind of the world economy will tell you, are deep and very hard to dislodge.

No Really, It’s Different This Time

Abe is not the first prime minister to apply stimulus in an effort to shake the economy out of its lethargy. Massive public works programs have been a hallmark of the past quarter century. Over this time, yields on the 10-year benchmark Japanese Government Bond (JGB) have never risen above 2 percent (including during periods when yields on US and European sovereigns were at 6 percent or higher). The 10-year yield’s trajectory is shown (green trend line) on the chart above. No amount of stimulus, it would seem, was enough to convince Japanese households to go out and spend more in anticipation of rising prices and wages.

So what is it about the current environment that could induce Japanese share prices to break the 50 percent curse for once and all? We would imagine the answer to be: not much. While it is true that both the US and Europe look set to continue a modest uptrend in growth and demand (with or without the reflation jolt catalyzing all those animal spirits), Japanese companies are not necessarily positioned to benefit – certainly not in the way they did in the very different economy of the 1970s-80s when “Japan as Number One” was required reading for MBAs and corporate executive suites. While they have arguably become more shareholder-friendly in recent years, as evidenced by higher levels of share buybacks and the like, corporate business practices remain largely traditional and hidebound. Just a decade ago, these companies blew a once-in-a-lifetime chance to ride the wave of the great growth opportunity that was China – in their own back yard.

There is no magic formula for growth. In a country with an old and declining population (and extremely strict limits on immigration), a supernova-like burst of productivity is the only plausible route to real, organic improvement. Until then, that barrier of 20,000 in the Nikkei may continue to be a tough nut to crack.