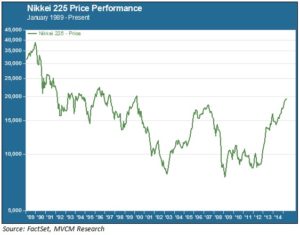

“Stocks always go up in the long run, except when they don’t” may be how Yogi Berra would have described the performance of Japan’s asset markets for the past quarter century. In the depths of the global financial crisis in early 2009, the Nikkei 225 stock index was worth less than 20 percent of the value it held (in nominal terms) at the giddy heights of the late-1980s shares and real estate bubble. The chart below tracks the pain long term Japanese investors have endured in their 25 year journey through the capital marketplace’s deep north.

Those long-suffering investors have been having a better time of it as of late, though. Since the election of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in late 2012, the Nikkei has jumped a cumulative 119 percent and has recovered fully half of the ground lost from its peak at the end of 1989. Shares are up more than 12 percent in local currency terms so far this year. Will the road to recovery continue? Or is halfway to breakeven as good as it’s going to get before winter comes again?

Honest Abe

Prime Minister Abe’s program for reinvigorating Japan’s moribund economy has three components, or “arrows”: monetary stimulus, fiscal expansion and structural reform. The Bank of Japan has certainly delivered on the first component. Japan’s quantitative easing program is larger in magnitude, relative to the country’s GDP, than either the Fed’s trio of QE sprees or the ECB’s more recent bond-buying bonanza. But the stimulus has thus far failed to deliver on the promise of igniting prices. Year-on-year core inflation as of March remained stuck at zero percent. And that is due at least in significant part to the chilling impact on domestic demand released by the second arrow. Consumer spending plunged in the wake of last year’s hike in the consumption tax, resulting in a negative GDP for the year. Consequently, Abe had to put the second arrow back in its sheaf, postponing the next hike in the consumption tax rate until 2017.

Arrows for Dinosaurs

That leaves the third arrow, by far the trickiest of all. Structural reform is never easy, least of all in the plodding, hidebound bureaucratic and corporate culture of Japan. The most notable single feat Japan’s collective business powers have accomplished in the last twenty years is conspicuously failing to take advantage of the growth opportunity presented by China Rising. In sharp contrast to the way they successfully penetrated the US market a half century ago, almost none of the leading Japanese companies managed to get in early and capture meaningful market share in China’s blossoming industry sectors. In contrast to the luster of, say, China’s Alibaba or South Korea’s Samsung, Japan Inc.’s once awe-inspiring brands are largely tired and shopworn.

With that said, though, Prime Minister Abe has taken aim at the famously thick red tape that has long made doing business in Japan a uniquely difficult challenge. He has pledged to submit at least twenty bills to the Diet (Japan’s parliament) this session to tackle key areas such as high corporate taxes, uncompetitive utilities, healthcare costs and pointless regulations. He needs to. Having failed to achieve the 2 percent inflation target by its original deadline, Abenomics needs a strong tailwind of economic growth to have any hope at all of having something to show for itself by 2018. A weak yen, low energy prices and low interest rates could still help here, but none of those variables can be relied on to continue for the foreseeable future and may conceivably reverse course.

Buybacks and Wages and Capex, Oh My!

What Abe would really like to see that third arrow do would be to tap into the deep well of cash businesses have been piling up for most of these lost decades. There are some signs that businesses are getting the message, announcing sizeable shareholder buyback programs and repatriating earnings from abroad to invest in domestic expansion programs. And with unemployment at a tight 3.6 percent, Japanese workers can expect to see a bump in their paychecks, which in turn could help boost consumer spending. The outcome of this year’s shunto – the annual negotiations between businesses and labor unions – was a 2.43 percent increase in wages. That’s real purchasing power at current inflation rates, and perhaps a sign of brisker times ahead.

Japan’s recent economic history makes it challenging to put too much faith in its ability to deliver the goods. If Prime Minster Abe is not able to produce at least one or two meaningful measures of success in structural reform by this summer, there may not be much additional upside in Japanese shares from their present levels. And the fiscal problems will have to be dealt with sooner or later – Japan’s budget deficit currently stands at 6.2% of GDP. But it would be advisable not to write final epitaphs for Abenomics just yet. The country has snapped back from daunting odds before. It may yet do so again.