As we write this commentary on Friday morning, Fed chair Jay Powell is still about 30 minutes away from giving his much-anticipated speech at the Jackson Hole, Wyoming meeting of central bankers that will wrap up today. So we don’t know exactly what Powell will say, but we imagine the following supposition won’t be far off from the truth: Powell will say that fighting inflation is the Fed’s top priority, that monetary policy will stay tight for as long as it takes to bring inflation back down to the central bank’s two percent target level, and that he and his fellow policymakers will take a strict data-driven approach to determining what specific actions make sense at each Open Market Committee meeting in the coming months.

We also know that the market will be looking closely for any comments that could support the “peak Fed” narrative supplying much of the fuel for the recent rally in equities: signs that inflation is at least starting to level off (today’s Personal Consumption Expenditures index is the latest sign that such leveling off may actually be taking place), and a prudential approach to not getting any more restrictive with rates than is necessary to get the job done.

What the market won’t be doing (because Mr. Market has an attention span roughly commensurate with that of a fruit fly) is dwelling too deeply on the lessons of monetary policy from the 1970s. But Powell, who is steeped in the history of his institution, will be very much guided by the lessons of the past: in particular, the stories of three Fed chairs from that era and their battles with inflation.

Arthur Burns and the Perils of Stop-Go

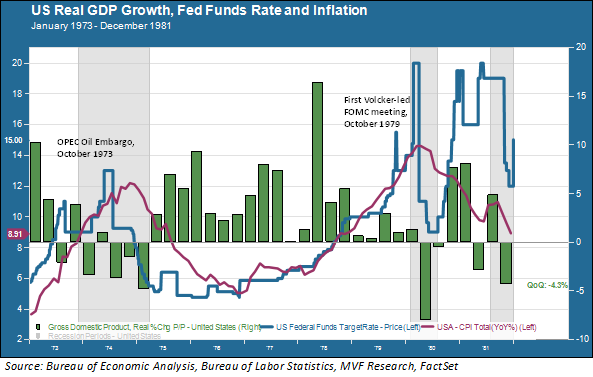

Arthur Burns was chairman of the Fed in October 1973, when US support for Israel in the Arab-Israeli War resulted in the OPEC cartel’s decision, led by Saudi Arabia, to place an embargo on oil exports to the US and other Israel-allied countries. As the above chart shows, the consequences of this action were dramatic. Oil prices, which had already been rising, quadrupled. Inflation (the crimson line in the above chart) shot up and the US fell into a protracted recession (the green columns in the chart represent quarter-to-quarter GDP growth).

The Burns Fed raised the Fed funds rate to 13 percent (blue line in the chart), but then dramatically cut the rate all the way back down to 5.1 percent to try and ease the harsh effects of the recession. The Fed, remember, has a dual mandate of prices stability and maximum employment, making decisions tortuously difficult when both inflation and unemployment are running high. Inflation eventually came down from over 12 percent to under six percent thanks to the recession.

But six percent does not qualify as low inflation. As the above chart shows, a series of stop-go rate decisions characterized the middle years of the decade, as the Burns Fed alternated between rate hikes to bring down inflation and rate cuts to spur employment and boost GDP growth. Inflation kept rising, however, and was back over seven percent by 1977.

Bill Miller’s Failed Incrementalism

In early 1978 the reins of Fed chair passed to G. William Miller, who began a series of very measured, incremental rate hikes. As you can see in the above chart, though, consumer prices kept going up right along with the rate hikes throughout the year. Meanwhile the overall economy, which grew at a relatively brisk clip during 1978, ran out of steam. Real GDP growth grew at an anemic pace in early 1979, while inflation surged back into double-digits. This was the real beginning of “stagflation,” the unsavory combination of low growth and high inflation. The Miller Fed’s continuation of tepid, incremental rate hikes did nothing to restrain soaring consumer prices.

Paul Volcker Starves the Beast

In mid-1979 President Carter appointed Miller as Treasury Secretary, and Paul Volcker took over the chairmanship of the Fed. Volcker understood that something different was required to break the cycle of high inflation. He believed that one of the key drivers behind the endemic inflation of the previous years was growth in the money supply, which needed to be restrained. The practical effects of this view soon became known, as the Volcker Fed in one fell swoop raised the Fed funds rate in October 1979 from 13 to 15.5 percent.

That was just the beginning: the Fed funds rate would go as high as 20 percent on two separate occasions before the central bank was finally satisfied that its work was done. The collateral damage was clear: the US economy suffered two deep recessions during 1980 and 1981, with high unemployment and sky-high interest rates choking off consumer activity across the economy. But inflation came down, and a new era of prolonged economic growth got under way.

More Now, Less Later

Jay Powell is an ardent admirer of the Volcker Fed, but he also does not want to be the central banker who has to choke off an economy in order to tame inflation. So while the current Fed chair gives his speech this morning, somewhere in the back of his mind are the lessons learned from the Burns Fed and the Miller Fed. A stop-go approach – which the stock market seems to be hoping for every time the word “pivot” comes up – where policy toggles between inflation and unemployment/recession, will diminish the bank’s credibility and ultimately fail to bring down inflation. An overly cautious incremental approach like the Miller Fed will not work if inflationary expectations are already baked into business and household spending decisions. Investors may not want to hear that a bit more toughness today is necessary so that things don’t have to be at Paul Volcker levels of toughness tomorrow. But that is the message we believe has been driving the Fed’s very consistent message on this topic over the past few weeks, and what we imagine will be the ongoing intention as Powell comes back from Wyoming and gets down to the business of preparing for the next policy meeting in September.