Shock and awe? That would be the right term to apply to the Swiss National Bank when it lifted the floor off the Swiss franc’s conversion rate against the euro last week. Any time currencies trade up or down in high double digits in the course of a single day should qualify in the annals of capital markets S&A.

Mario Draghi and the European Central Bank? Not so much. The announcement of the €60 billion quantitative easing program, to last at least through September 2016, was impressive to be sure, but it was also widely expected. European equities rallied, yields compressed and the euro continued its descent against the dollar, but all in modest single digits. What remains to be seen is whether Helicopter Mario’s efforts will bear fruit in bringing about a meaningful change in direction to the Euro area’s beleaguered economies. What seems likely, in the near to intermediate term, is a continuation of the Dire Straits Economy on both sides of the Atlantic. Money for nothing and your bonds for free.

Incredible Shrinking Yields

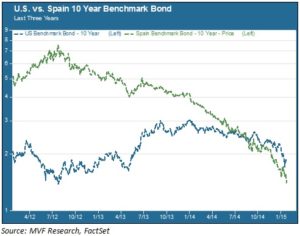

Your value equation as a fixed income investor is pretty simple. You want to preserve purchasing power. You want to be compensated for deferring until tomorrow the consumption opportunities of today. And you want an additional something in exchange for whatever risks come with the investment. That’s basically it. Now, consider the sovereign yield trends over the last three years in two countries – the U.S. and Spain – in the chart below.

How times have changed. Three years ago the spread between the 10 year Treasury and the 10 year Spanish sovereign was more than 5% – reasonable, it would seem, given the considerable risk prevailing at the time that the Eurozone would break up and Spain, as one of the troubled peripheral economies, would be adrift in a storm of Biblical proportions. Today the spread is negative – Spain’s benchmark debt yields less than the U.S. The same is true for almost every other Eurozone country. Yields are low and continue to shrink. What does this tell us about that fixed income value equation – purchasing power protection, the time value of money and risk spreads?

Deflation Trumps All

Mostly, it seems to tell us that bond investors have a very dim view of the prospects for growth, anywhere in the world. The negative spreads between Treasuries and Euro area debt have very little to do with relative risk factors and almost everything to do with the distorting effects of deflationary expectations on traditional valuation models. Deflation turns the first two components of the value equation – purchasing power and time value – on their heads. If inflation is zero or lower you don’t lose purchasing power. If prices are actually going to be cheaper tomorrow than they are today then you don’t need any extra inducement to defer consumption. If today’s yields reflect a rational consensus about future economic prospects, that consensus apparently is that there’s not going to be much growth, anywhere, anytime soon.

What About the Growth Narrative?

But isn’t that consensus out of line with the growth story, at least in the U.S.? We had real GDP growth of 5% in the 3rd quarter last year and 4.6% in the quarter before that. The last time we had real growth at that level was in 2003 – when the 10 year Treasury was yielding around 4% and inflation was 2%. Unemployment is lower today than it was in 2003. All chatter about a “new normal” notwithstanding, is 3%-plus real GDP growth truly compatible with sub-2% intermediate term interest rates?

There is no certain answer to that question, but as long as inflation remains all but invisible it would probably be a good idea to let the bond market lead this dance. Rates in Europe may not be far from their lower bounds, but there is still room on the downside. After all, even at a 1.4% nominal yield, real rates are still higher in Spain, where inflation is negative, than they are in the U.S. And if recent history serves as any guide, we can expect quite a bit of that QE money tossed out of the ECB’s fleet of helicopters to land in asset markets in the U.S., including Treasuries.

“Rates will Rise” was the mantra at the beginning of 2014. “Lower for Longer” seems an appropriate corollary for the current times.