Like many of our peers in the industry, we have spent much of the past few months looking at the bond market from every angle, shaking it, turning it upside down and trying to figure out what message it is sending. At face value there doesn’t seem to be a single, consistent message here. Credit risk spreads – i.e. the additional compensation investors are supposed to demand for holding riskier assets than super-safe government bonds – remain tight. The current spread between Baa investment grade corporates and the 10-year Treasury yield is 1.8 percent, as compared to the three-year average of around 2.2 percent. Over in high yield land the ICE BofA High Yield Bond index currently yields 7.9 percent, compared to a high of 9.5 percent last fall and well below the yields normally seen during economic slowdowns.

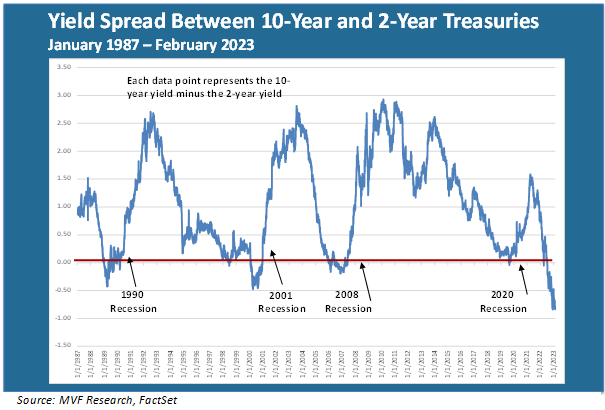

But while credit risk spreads seem to be telling us that everything is fine and dandy, the Treasury yield curve is more deeply inverted than it was at any time during the four previous recessionary periods.

Nobody knows for certain, of course, what the economy is going to look like later this year, but the consensus among economists is that we will have a slowdown with a decent likelihood of a shallow recession (the shallow recession is our base case view, as we have communicated in previous commentaries). So when we consider the depth of the current inversion, what comes to mind is that perhaps the shape of the curve is not as much about signaling a recession as it is about other things. But what other things?

Yesterday On Their Minds

The vast literature of behavioral finance may offer some clues about what is going on with the bond market’s seemingly split message that may in fact be not so split at all. One facet of human predilections flagged by behavioral economists is a recency bias. That’s when your expectations about future outcomes are rooted in your experience from the recent past. For bond investors, the single most salient element of recent history was ZIRP – the zero interest rate policy that dominated the post-2008 financial crisis environment and influenced fixed income instruments of all types and maturities. The average 10-year Treasury yield from the beginning of 2010 to the end of 2021 was 2.19 percent. Short-term rates, of course, were closer to the zero lower bound of the Fed funds rate.

If you assume that the 2010 – 2021 cycle represents some kind of natural norm for any future growth cycle, then it’s easy to see why you might be bidding up 10-year Treasuries today (i.e. putting upward pressure on prices and downward pressure on yields). The 10-year today is at 3.7 percent, the Fed is closer to the end than the beginning of its tightening cycle, the recession (if it happens) will be brief and then things go back to where they were. If 10-year paper is back around two percent twelve months from now, then holding bonds with a 3.7 percent yield looks pretty smart.

Thinking About Tomorrow

The problem with recency bias, of course, is that the immediate past is not likely to be an accurate guide for the characteristics of the next cycle. We already have a pretty good sense that one major component of the economy – the jobs market – is not going to look much like the experience of recent decades. Structural demographic trends are starting to come into play, and these trends have the potential to keep some degree of upward pressure on inflation. That, in turn, may have an impact on where the Fed decides interest rates have to be as the current tightening cycle transitions to something else. We do not expect that the Fed will start cutting rates any time soon; even when it does, nothing we see today suggests that we are headed back for a reprise of the ultra-easy money conditions of the 2010s.

To sum it all up: we think the face-value split message between tight credit spreads and the inverted yield curve is not really a split message, in that the reason for the inversion has less to do with fears of a looming recession than it does with general views about interest rates anchored in the experience of 2010 to 2021. That’s where we see potential mispricing, because if the Fed is not going to cut rates dramatically (because this next economic cycle is not going to look like the last economic cycle) then we should not assume that a 10-year yield of two percent is where we wind up in another year or two. We’ll know more as we see data about growth, prices and jobs come in over the next few months. But we think this might be a good time to resist that behavioral trap of recency bias.