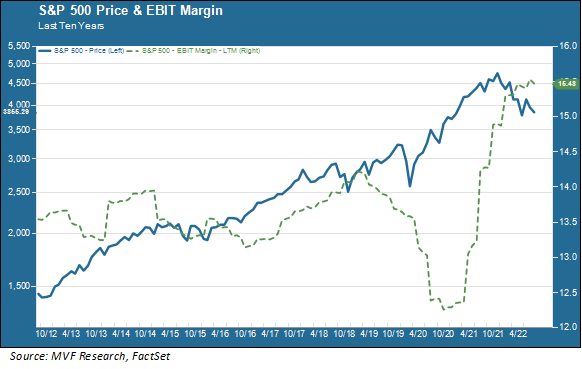

Two earnings seasons have come and gone this year, and in both instances the takeaway was something along the lines of “could have been worse.” Concerns that rising inflation would have a negative impact on sales growth and profitability margins have not turned out to be as dire as some were expecting. In fact by one very important measure – operating profitability – S&P 500 companies on the whole are doing better than ever. The chart below shows earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) as a percentage of sales over the past ten years (the green dotted line). As you can see, the current EBIT margin of 15.5 percent is close to its highest level of the past decade.

Income, Jobs and Prices

Much of the recent strength in profit margins has been driven by price realizations. Companies facing higher input costs – raw materials, logistics & transportation, labor – have been able to offset those increased expenses by raising the price of the goods they sell to their own customers. The main reason for this is that consumer demand has remained resilient. Some of that has to do with the lingering effects of pent-up spending urges following the pandemic, and some of it has to do with the lower availability of many types of goods still impacted by dysfunctional supply chains. If more people want to buy, say, a bicycle and there aren’t as many bikes in the store as there were in years past, then your local bike shop will have no problem raising the price by a hefty amount (and if you have been out bike shopping any time in the past twelve months you know that this indeed is what has happened).

All that works fine…until it doesn’t. Resilient consumer demand has benefitted from a labor market that continues to run hot, and sufficient levels of personal income. The unemployment rate has remained at or close to 50-year lows throughout this year, with unusually high levels of job vacancies being a much bigger story than layoffs or salary cuts. But that appears to be changing. Although the evidence has been largely anecdotal up to this point, we expect that the upcoming earnings season will feature more reports from management teams about downsizing plans as the macroeconomic outlook turns down. When that happens, spending patterns will change as well. Those easy price increases will be a thing of the past, which suggests that we are probably at the point of peak margins.

Ship, Deliver, Warn

FedEx is one of the companies analysts use as a bellwether for global economic conditions. The shipping and packaging giant has its pulse on the highways and byways of global commerce, so when it comes out and says that things are looking pretty bad, Wall Street pays attention. The company came out after the closing bell on Thursday afternoon with a preliminary report on the three months ended August 31, which threw a wet blanket on investor sentiment in a week when sentiment really did not need yet another downer. The company missed analyst earnings expectations, withdrew forward guidance for the rest of the year and noted in particular that the rate at which conditions are worsening picked up considerably in the last few weeks of its fiscal quarter. Store closures, parked airplanes and a general hiring freeze will go into effect immediately; layoffs are probably not far behind.

This is what Fed chair Jay Powell meant a few weeks ago in his Jackson Hole speech when he warned that the Fed’s efforts to tame inflation will likely create economic pain. Pain will come in the form of higher unemployment, weaker consumer demand and – yes – lower profit margins. For investors, is this a sign that it’s time to run for the hills and build up the cash defenses? For portfolios with time horizons beyond the next couple years, we believe the answer is no.

What is happening now is actually closer, in our opinion, to a textbook economic cycle than anything we have seen in the last couple of market convulsions (i.e., it is not a meltdown of the financial system circa 2008, nor is it an acute global health crisis a la 2020). The thing about economic cycles is this: they pass, and the downturn reverts back to growth. What the economy will actually look like on the other side of this cycle is still unclear – but that is a discussion for another day.