Do politics matter for markets? We generally have a standard and perhaps somewhat annoying answer to that question, which is “typically no, but sometimes yes.” Short-term market movements normally react to political developments only when those developments pertain directly to changes in interest rate policy or tax policy, since those are two variables that, when changed, have an immediate effect on cash flow valuation models. For the most part, our experience is that political events which may seem huge in Washington or Brussels or London resonate weakly, if at all, in financial markets. But “for the most part” is not the same thing as “always,” which brings us to the events of this week.

From Walpole to Truss

Great Britain has had prime ministers for more than 300 years, starting with the eminent Sir Robert Walpole in 1721. So it was pretty impressive, and not in a good way, when Liz Truss this week became the shortest-lived PM in that entire span of three centuries, spending just 44 days in residence at 10 Downing Street before being shown the door this past Wednesday. Those were not a good 44 days for our friends across the pond. Let’s look at it from a market perspective.

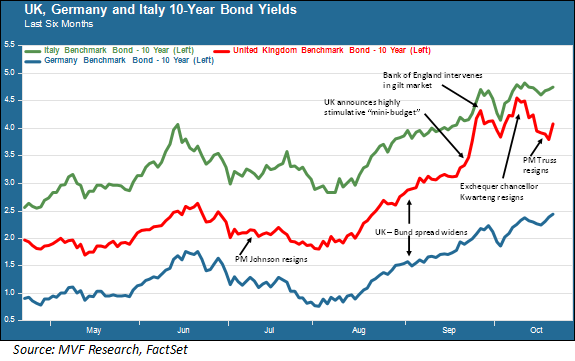

Here in this chart we show the past six months’ trend in the bond market, looking at one normally stable benchmark issue (German Bunds), one typically volatile security (Italian sovereigns), and a sovereign issue which appears to be reclassifying itself from “stable” to “not as stable,” namely UK gilts. If we go back to the period between April and July we see a fairly stable relationship between the yield trends of the UK and German bonds (the blue and red lines respectively). Italy (the green line), true to form is more volatile.

In early July former UK prime minister Boris Johnson resigned, setting off a contest within the ruling Conservative Party to select the next prime minister. We’ll come back to the question of this selection process later, because it is germane to our theme of politics and markets, and because it is happening again with the Truss resignation. For now, we can see that the immediate aftermath of the Johnson resignation itself did not do much to change the basic spread relationship between gilts and Bunds.

Starting around mid-August, though, the pattern started to change. Gilt spreads started to widen versus the Bund and in fact started to look more like Italian bonds. Interest rates were rising across the board in this period, but the rate of change (which is what matters when we’re talking about spreads) was more pronounced for UK and Italian bonds than for the German benchmark. From a political standpoint, this was the period when the likelihood of Liz Truss becoming the next prime minister came into focus. She was campaigning on a platform of “growth at all costs” which raised the specter of the policies, like massive unfunded tax cuts, that her government would indeed wind up trying to implement when they came into power in early September – at the same time that the Bank of England was trying to fight what by then had become double-digit inflation.

Not Cool, Britannia

The chart then highlights the key events that roiled the gilt market following the announcement of this planned fiscal stimulus on September 23. Gilt yields soared, then fell back when the Bank of England intervened, then rose again when the BoE put a firm exit date on its intervention, then fell again when the controversial exchequer chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng resigned, followed of course by the resignation of Truss herself this week. In early trading today they have jumped again sharply – not a good sign.

The sharp fall in gilt yields since Kwarteng resigned (which effectively took all those ill-conceived tax cuts off the table) might raise hopes that UK sovereigns will return to their conventional ways and trade with more predictability against other stable benchmarks. We do not think that is likely, and not just because of this morning’s sharp reversal. Here we get to the essence of when politics can have a more long-lasting effect on markets. Recall that Truss’s selection as prime minister was not the result of a general election in which all the voting public participated. It was a party-only contest, first decided by Conservative Members of Parliament and then by citizens who were current dues-paying Tory party members. It was estimated that less than one percent of the country actually cast a vote in the process that eventually brought Liz Truss to power.

Now that same highly selective, undemocratic process will play out again (with the added possible spectacle of former PM Johnson throwing his hat back into the ring). The leader of the opposition Labour Party, Keir Starmer, has called for a general election to decide the next government. This won’t happen, though, because the Conservative Party knows it would lose a general election were one held today. The Tories (Conservatives) are currently polling around 14 percent approval versus 53 percent for Labour.

The result of this is that come November, the UK will have had three prime ministers in the space of four months, two of whom were not the winners of any kind of a general election. That, to put it mildly, is not what is expected of an economy (or society, for that matter) as developed as the UK’s. Even Italy, which also cycles through governments at a fairly brisk pace, looks better in comparison. Britain’s next scheduled general election could be as far away as January 2025. That’s a lot of time for more chaos, and for the credibility of the country’s troubled institutions to fall further still. It’s a lesson that other developed countries with their own political problems should heed: it may not always seem like chaotic politics matter for markets, but there can be a price to pay, and in the bond market that price can be very real.