We learned many things about the world on Thursday. As usual, some were edifying and others were beyond cringeworthy. One the one hand, we found out that the total output of the US economy, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), fell by an annualized rate of 32.9 percent from the previous quarter, by far the largest quarterly drop since recordkeeping began in 1947. On the other hand, the collective quarterly sales of four prominent enterprises – Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook – rose by $32.6 billion from their levels one year ago a double-digit increase. Take that, coronavirus!

The GDP numbers came out at 8:30 am, before the markets opened. The companies reported their earnings after the 4:00 pm market close. In between those bookends the S&P 500 dithered along in negative but not too negative territory, as if to say “sure, the economy’s in a pretty crummy place, but technology, amirite?” Indeed, the stellar performance of technology stocks throughout the pandemic has helped make the relationship between the market and the economy different, entirely different, from that of the other two recessionary periods of this century.

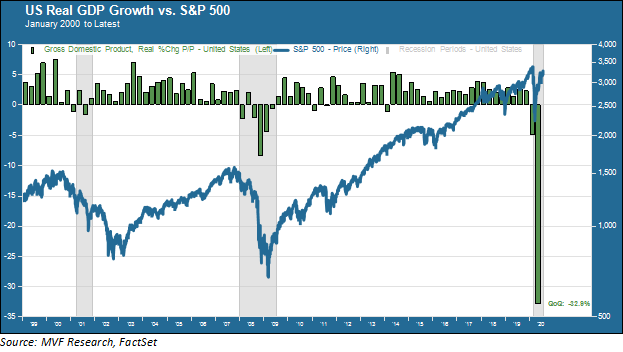

The chart below shows the stock price performance of the S&P 500 against real GDP growth since 2000. Contrary to the 2001 recession and the more painful one of 2008, this time there has been no sustained drawdown in stock prices. Things went from fear to FOMO in no time at all.

The Tech-onomy

Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook are expected to produce about $900 billion in total revenue for calendar year 2020 (based on already-reported results and analysts’ forecasts for the remaining two quarters. Adding Microsoft – the other member of the Big Five that had already reported before yesterday – puts that total well over $1 trillion. That’s no small amount of money. But neither the revenue contribution of these firms, nor their profitability, nor other operational metrics like employee headcount or productivity make them notably different from market leaders of earlier eras – think General Motors in the 1950s, or ExxonMobil (then just Exxon) in the 1970s or IBM in the early 1980s – in the context of their size and contribution to the overall economy.

Where today’s Big Five stand out is their stock market capitalization, defined as the stock price per share multiplied by the number of shares outstanding. Their total market cap runs to $6.3 trillion (based on 7/30 closing prices). That’s just under 23 percent of the market cap of the entire S&P 500. It’s also 32 percent of the total US GDP of $19.4 trillion following that sharp second quarter collapse.

What all of this means is that while today’s technology leaders are not demonstrably more important to the overall economy than the leaders of bygone dominant industries were in their day, they are valued much more highly by the stock market. When you hear someone say “the stock market and the economy are not the same thing,” here is Exhibit A. Now, this clearly is not the only reason why the current stock price performance in that above chart looks so different from that of previous recessions – and tech outperformance was a pre-existing condition before Covid-19. But it is a meaningful contributing factor.

A Bridge to Nowhere?

There was another bit of news yesterday that was overshadowed by the combination of economic releases and clownish performative politics intended to distract (we will just leave that one there). Or, rather, non-news, since it would have been news if legislators on Capitol Hill had managed to reach some form of agreement on a new relief package before the expiration of benefits from March’s CARES Act, which expiration happens today. But there is no agreement in sight, with the White House and Senate Republicans talking past each other, let alone engaging constructively with Democrats.

One f the basic go-to explanations for optimistic sentiment in the stock market has been the imagery of a bridge. Congress and the Fed set the foundations back in March – with the CARES Act and the Fed’s multifaceted liquidity facilities – with enough raw materials (money and other benefits) to extend through the middle of the summer. By then we should either have arrested the spread of the pandemic or, if necessary, had enough time to come up with a way to extend the bridge further out. Neither of those things happened. Today we are standing at the edge of that unfinished bridge and the other side is still a very long way away.

Perhaps nobody has been more articulate, more emphatic, and indeed more empathetic about the importance of extending household and business relief than Fed Chair Jerome Powell. In his press conference after this Wednesday’s FOMC meeting Powell once again spelled out the plain facts: this is a health crisis the time line of which is driven entirely by the virus, not by economic wishful thinking. To avoid having temporary economic reversals become more permanent, fiscal policymakers need to do their part. If that doesn’t happen then the “fiscal bridge” erected in March becomes a bridge to nowhere. That has dark implications for the resilience of this market rally, with potential consequences neither supercharged tech stocks nor the Fed itself may be able to blithely swat away. It wouldn’t take much for FOMO to revert to fear.