Financial theory teaches us that market prices are driven by the outcomes of perfectly rational creatures making split-second decisions fine-tuned to the optimal net present value alternative. Those of us who live in the practical world of investment management know that this particular slice of financial theory is, not to mince words, bunk. Markets are many things, but perfectly rational they are not. Still, we are sometimes surprised by how willfully irrational markets can be. Perhaps none more so, in recent times, than the bond market.

Memo To: Market, From: FOMC, Re: Rates

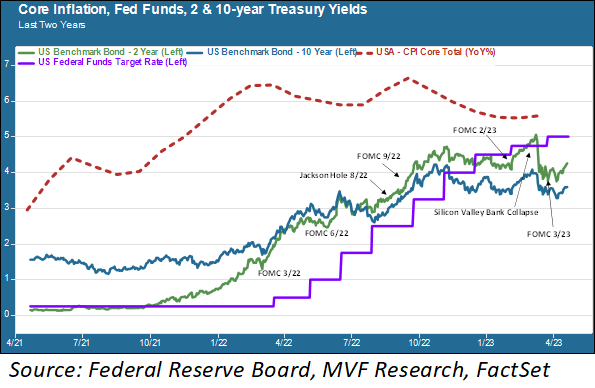

There has been a distinct pattern in the bond market ever since the Fed first began to raise rates in March last year. We think of this pattern in the imagery of a memo from the Fed to the market: hey, we are doing this, please pay attention. And pay attention the market does…sometimes for a few days, sometimes longer, but sooner or later one of two things happens. Either some shiny new thing comes along to distract attention away from the Fed’s stated intention, or investors fall into the behavioral trap of recency bias, assuming that the immediate future is going to look a whole lot like the decade from 2010 to 2020 when the Fed reliably brought rates down every time things started to look a little dicey. We have helpfully charted this dynamic on the chart below.

Here’s what this chart tells us. After the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced its first rate hike in March 2022 rates predictably went up (we show both the 2-year and the 10-year Treasuries here for illustrative purposes, with more focus on the 2-year because it is typically more sensitive to Fed decisions). Rates actually eased a bit at the 2022 May meeting because investors perceived a “dovish” underlying message from the FOMC. They heard wrong, because in early June the FOMC went ahead with a 0.75 percent rate hike and an accompanying message that bringing down inflation was job numbers one, two and three at the Fed. You can see from the above chart where core inflation (the crimson dotted line) was relative to interest rates at the time of the June ’22 meeting and indeed where it remains today.

Peaks Versus Mesas

But even the 0.75 percent June Fed funds hike was not enough to convince the bond market that rates were going to stay higher for longer (a phrase the Fed has used almost continually throughout this period). Inflation seemed to be levelling off as the summer proceeded. As you can see from the chart, “levelling off” is not the same thing as “peaking and then falling sharply,” which was what seemed to drive market sentiment. The inflation trend looked more like a mesa – roughly flat at an elevated level – and less like the Matterhorn.

But rates trended down until a series of sharply-worded memos seemed to get through to the market in the space of about eight weeks from late July to mid-September. First, another 0.75 percent rate hike at the July meeting. Then, a very hawkish speech by Fed chair Powell at the annual gathering of central bankers in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in April. Finally, a third hawkish 0.75 percent Fed funds hike at the September FOMC meeting.

Bond FOMO

Now we are in fall 2022 and a new dynamic is making itself felt. We all know about FOMO (fear of missing out) in the wackier parts of the market like meme stocks and crypto. But in the staid, buttoned-up bond market? Yep. Investors looked at nominal yields they hadn’t seen for a generation (let’s not talk about real yields, since those were obviously still terrible from a purchasing power point of view) and wanted in. More demand for those yields meant that those yields started going the other way, even though (a) inflation was still high and (b) the Fed kept saying it was going to keep rates – all together now – higher for longer. But self-styled bond gurus showed up on CNBC with their versions of “chance of a lifetime” and the mania was on.

SVB and the Pivot Play

The FOMC meeting at the beginning of February this year was another sternly-worded memo from the Fed to the bond market, and as you can see from the above chart it had the near-immediate effect of cooling off the bullish bond sentiment. Rates on the 2-year Treasury jumped above five percent for the first time since 2007. It looked like the memo might finally have gotten through for once and for all. Then came Silicon Valley Bank.

The biggest US bank failure since 2008 caused an immediate repricing of just about everything related to interest rates and monetary policy. The Fed joined other regulators in the liquidity-providing measures put together in the weekend after the bank’s failure, which led to a new narrative that the Fed was in fact going to start cutting rates. Once again, the narrative had no basis in anything the Fed was actually saying. The FOMC’s March meeting came just 13 days after the SVB collapse. Rates went up by another 0.25 percent. Both Powell’s comments at the post-meeting press conference and the Summary Economic Projections supplied by the Committee members transmitted the message that rate cuts were not in the FOMC’s base case planning scenarios for 2023.

And yet, a Fed “pivot” to cutting rates, to the tune of about 0.6 percent remains priced into where bonds are trading today. We do see in the chart above that rates have crept up a little bit in the past few days. And we regularly hear from a number of prominent figures in the market – today it was Jonathan Gray, president of private equity giant Blackstone – warning that the market is to a great extent ignoring reality in its fixation on the illusory Fed pivot.

We do understand the charms of higher yields that have generated higher demand for high-quality fixed income securities. If you think inflation is going to be back below, say, three percent by sometime in 2024 and you can lock in a five-year nominal yield of four or five percent then there is a logic to that trade. It’s a judgment call (and, frankly, a bet on outcomes that we simply don’t know and can’t know at present). But if you are chasing total return on your bond portfolio because you think rates are going back down to their levels of the 2010s – well, that smacks of recency bias and in our opinion is not a rational course of action given where things stand as of the present. The bond market today is – to use a word that is coming up more and more among participants in it – wacky. It requires care, caution and discipline.