The news this week has been mostly on the positive side when it comes to the virus. New cases in the US are down from the lofty 300,000+ levels of last month to the low 100,000s (though in a broader context that is still on par with the levels seen during the mid-late summer surge last year). The fatality rate is still much too high for anybody’s liking, but that should start to trend down in the wake of lower daily cases.

On the vaccine front, Johnson & Johnson has applied for FDA approval for its jab – although the efficacy appears lower than that of the other two US-approved vaccines it still comfortably clears the FDA’s standard minimum efficacy threshold of 50 percent. And the AstraZeneca vaccine (approved for use in the UK and parts of the EU, though not yet in the US) appears to have additional capabilities in helping to reduce incidence of transmission. Even Sputnik-V, the much-derided Russian vaccine, is getting a second look from EU regulators. Hey, if it works it works, regardless of origin, right?

Fiscal Relief Odds Increase; So Do Interest Rates

The bond market has been putting its chips on the likelihood of the Biden administration getting its relief bill through Congress. That bet got a boost last night when the Senate worked its way through a tedious list of more than 800 proposed amendments to agree (by simple majority) on the $1.9 trillion package, setting up the somewhat arcane budget reconciliation process through which a bill can pass through Congress without triggering the Senate filibuster (which would require 60 votes and thus Republican support that appears not to be forthcoming). The already steep yield curve could add some further degrees of difficulty to that slope.

Follow That Dotted Line

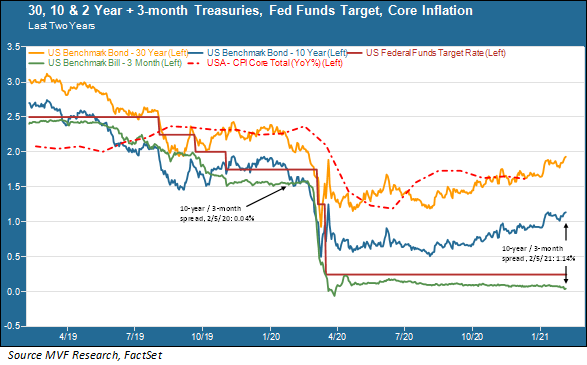

Why is the bond market so confident that rates have further to rise? After all, the Fed has no intention of raising short-term rates any time ahead as far as the eye can see. The Fed funds rates and short-term Treasuries, respectively the solid crimson and green lines in the above chart, are likely to stay tethered to zero for many months, if not years, to come. Core inflation (the dotted red line) has been well below the Fed’s two percent target rate since the pandemic began. As we have mentioned several times in recent commentaries, inflation has not been a significant economic factor for many decades.

But that $1.9 trillion relief package is going to bring a lot of new money into the economy at a time when the economic news is neither uniformly bad nor demonstrably getting worse. Three different jobs reports this week – the ADP survey midweek, the weekly initial claims number yesterday, and the monthly BLS employment report today – all point to conditions that are at least stabilizing in the labor market if not yet turning into growth. By the time the money from the relief package actually gets put to work on behalf of households and small businesses, millions more Americans will have received a vaccine, increasing the likelihood that we will not see another surge in new cases similar to what happened last fall.

Demand Hot, Supply Not

The most likely outcome of this convergence of improving health and improving finances is a temporary – this is the key word and we will come back to it – imbalance between the demand for goods and services and the supply of the same. Global supply chains are still working out the disruptions experienced last year. Many small and mid-sized businesses, particularly service providers like restaurants, beauty salons and mom & pop retailers, have gone out of business (and there will be a lag before new enterprises come along to replace this lost supply). More money will be chasing fewer goods – and that is the textbook definition of inflation. Higher inflation in turn will continue to put upward pressure on interest rates in maturities beyond the direct reach of the Fed’s short-term zero lower bound target.

Back to that key word – temporary. If this supply-demand imbalance is a one-off phenomenon that flashes like a supernova between, say, April and December of this year then it should not be a longer-term concern. That is the scenario Fed chair Jay Powell articulated in the post-FOMC press conference a couple weeks ago. Inflation may jump up well above the two percent threshold for that time – and longer-term nominal Treasury yields would probably follow suit – but then subside back closer to recent historic trends hovering below or at that threshold, with a resumption of slow growth and restored equilibrium between supply and demand. No harm done.

Still, that $1.9 trillion of new money coming into the economy is hardly chump change. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the largest relief package in US fiscal history was the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Obama administration’s program to stimulate the economy after the financial crash and recession of 2008. By comparison the smallest – smallest! – of the pandemic relief packages – the one signed into law last December – ran to $900 billion.

Unquestionably this tsunami of relief has helped us get through this terrible period much better than we would have otherwise. But we still do not know how much of an impact all this new money will have on an ongoing basis, once the virus and the economy it created have disappeared beyond the horizon of the rear-view mirror. We will have the answer in due course.