It was a giddy era, a time of seemingly endless possibilities. At the beginning of 2000, New Media upstart AOL announced a planned takeover of one of the storied blue-bloods of the print world, Time Warner. Silicon Valley was awash in engineers and secretaries alike cashing in their millions in stock options and buying vineyards in Napa Valley. Affixing a “dot.com” to the name could turn just about any run-of-the-mill business proposition into a high-flying multimillion dollar enterprise.

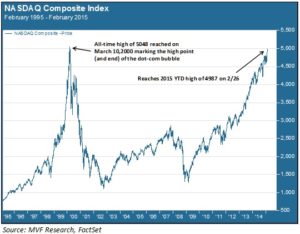

And then it all ended, horribly. The NASDAQ Composite index, home to virtually all the newly-minted Internet hotshots, crashed through record high after record high on its way to 5048, the March 10, 2000 close. And that was the last time NASDAQ ever saw daylight, to paraphrase the movie Titanic’s Rose Dawson. In fact the trajectory of NASDAQ’s rise and fall bears appropriate resemblance to an iceberg, as shown in the chart below.

The Long Road Back

Well, it may have taken 15 years to get here, but the NASDAQ Composite is now poised to put the final coda on the Great Macro Reversal of the 2000s. The S&P 500 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average both surpassed their previous records in 2013. NASDAQ is the third of the so-called headline U.S. stock indexes, the ones that news announcers unfailingly recite in their daily financial news segments. Of course, there is nothing intrinsically special about 5000 or 5048 – a price by any other name is still just a price. But perception often becomes reality, as long-term students of the ways of markets understand. Round numbers and prior highs matter because they are triggers embedded in the bowels of thousands of algorithms. When the trigger activates, the money flows. Momentum doesn’t last forever, but it can lend a tailwind to near-intermediate term price trends.

Not the NASDAQ of Yore

Beyond the “NASDAQ 5000” headlines there are fundamental differences between the index circa March 2000 and that of today. Nowhere is that more clear than in a valuation comparison. At its 2000 peak, NASDAQ sported an eye-popping LTM (last twelve months) P/E ratio of 100. Of course, many of the most popular trades of the day didn’t even have a meaningful “E” to put in the denominator of the equation – they had no earnings to speak of for as far ahead as the eye could see. Investors bought these first-gen Internet companies on a wing and a prayer.

Today’s NASDAQ includes a handful of survivors from the Fall, as well as others that have made an indelible mark on the world since. The top 15 companies by market cap on the index (which collectively account for just under 40% of the total market cap of all 2500+ companies listed on the Composite) are a veritable Who’s Who of the industry sectors at the forefront of U.S. economic growth. Leading the way is Apple, of course, with a $750 billion market cap and a stranglehold on the smartphone industry. Apple’s share of all global operating profits from smartphone sales was an astounding 89% in the 4th quarter of 2014.

The other names in NASDAQ’s elite bracket are likewise familiar, including Internet giants Google, Amazon and Facebook, biotech leaders Gilead and Amgen, mobile chip maker Qualcomm and still-feisty Microsoft. Now, it’s still not a particularly cheap proposition; the average LTM P/E for this top 15 is 29.1 versus 20.5 for the entire index (which in turn is about a 1.15x premium to the S&P 500’s LTM P/E of 17.8). At the same time, though, it is a very far cry from the silly nosebleed valuations prevailing at the turn of the century.

L’économie, c’est l’Internet

In 2000 the Internet still accounted for only a small sliver of real economic activity. Social media had yet to be born, online retailing was still embryonic, and few companies outside the tech sector had any real clue about how the New Economy affected them, beyond the basic effort of putting up a static corporate website. In the span of fifteen years, the Internet has come in from the periphery to envelop practically every conceivable sphere of economic activity. By all appearances, its influence will only grow more pervasive. Now, this of course does not mean that NASDAQ has nowhere to go but up. At some point a significant correction will likely be in the cards. But it seems hard to imagine how a properly diversified portfolio in the second decade of the 21st century could avoid meaningful strategic exposure to the NASDAQ Composite’s leading lights.