The financial world loves itself some acronyms to sprinkle into everyday conversations, often the more obscure the better. We generally take pains to avoid the word salads of capital markets gobbledygook, but every now and then we come across some constructs that really can help our clients understand what’s going on out there. Thus the central feature of today’s column: NIRP – Negative Interest Rate Policy – and TINA, which refers to the equity market and stands for There Is No Alternative (i.e. to common stocks and their ilk). NIRP and TINA are joined at the hip and explain much of how markets behave in the strange world we inhabit.

From Fanciful Theory to $16 Trillion Reality

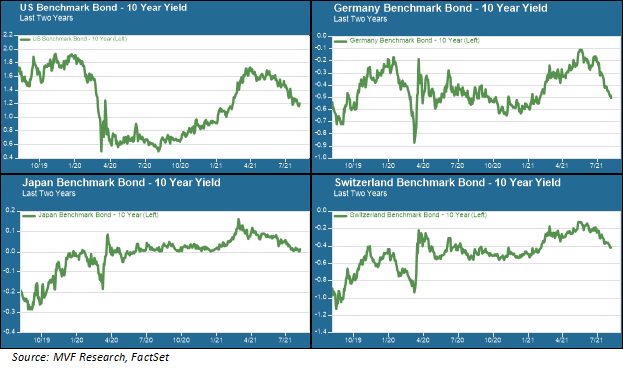

It’s worth remembering that up until the last decade, negative interest rates were the stuff of abstract theory, running contrary to the most fundamental assumptions about practical finance (e.g. the time value of money). But that was then. Today the volume of fixed income securities trading with yields below zero runs to $16.5 trillion, having grown steadily over the past two months with the renewed rally in global bond prices. As the chart below shows, yields have fallen steadily in all major bond markets over this time.

Why have yields fallen so much since late spring, and why on earth does anyone want to invest in something like a German or Swiss 10-year bond that, if held to maturity, explicitly guarantees a loss? Two fair questions. Generally speaking, high-quality government bond prices go up (i.e., yields go down) when sentiment about economic growth turns negative. That might seem odd, because for the most part major economies right now are growing at faster rates than they have for many years. Expectations of faster growth – and with it, faster inflation – drove a sharp rise in yields during the first three months of the year.

But in the second half of May that sentiment seemed to shift. Rather than focusing on the growth taking place in the present – which after all is coming directly on the heels of the sharp contraction last year – the narrative shifted to what was likely to come next. Peak growth (which we talked about in our commentary last week) replaced reflation as the catchphrase for market sentiment.

Not so fast, say some who are not entirely convinced by the peak growth narrative. The ultra-low yields we see today are less about economic fundamentals than about some technical factors, including some reversals of bearish bond bets by major institutional players and, not least, by the outsize influence of central banks and their continued bond-buying programs during the relatively quiet summer months.

Enter TINA

You can’t understand the answer to that second question we posed above – why would anyone buy a 10-year note with a negative coupon rate attached? – without understanding the pre-eminent role that central banks play in these credit markets. The European Central Bank currently buys €87 billion worth of debt securities every month as part of its current monetary policy. The Fed buys $120 billion worth of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities each month (as a reminder, the Fed does not support a negative interest rate policy at present, while the ECB does).

While the central banks have more direct control over short-term rates than they do at longer maturities, their actions nonetheless have an impact at all points along the yield curve. Including those baffling markets where rates are negative. Institutional investors like insurance companies and pension funds may hate negative rates with a passion, but their investment policy statements give them little choice but to hold at least some of them in the low-risk portions of their portfolios.

And that brings us to TINA. Low interest rates – whether barely above zero or firmly in NIRP-land – are fundamentally unappealing to investors. Even in the US, where nominal Treasury rates are not negative, real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) interest rates are decisively negative and at historically low levels. Where do you go if you want some preservation of purchasing power for your hard-earned capital? Equities, and other instruments with higher income streams from dividends and the potential for capital appreciation. Central banks have effectively pushed investors, institutional and individual alike, to allocate more of their portfolios to higher-risk assets in search of adequate rates of return.

All of which is fine, as long as the central banks are there to flood markets with liquidity whenever things turn south. The so-called “central bank put” has been institutionalized practically to the point of being set in stone. Bear in mind, though, that regular put options come with expiration dates. Should the central bank put ever reach an end date, TINA’s charms may seem considerably less so.