In last week’s market commentary we argued the case for why a near-term melt-up – a giddy rally in the stock market through the remaining months of 2019 – might be in the cards. One week later we see continued evidence that, if not exactly a go-go 1999-style event, conditions seem to be in place for at least consolidating the already sizable gains made in the market this year. The earliest batch of Q3 corporate earnings is out and, while not particularly stellar, the numbers seem to fall roughly within consensus expectations. The Fed meets next week and is likely to come through with another rate cut (at least according to the Fed funds futures market, where a 0.25 percent cut presently has an 82 percent probability of happening). Sentiment around the trade war seems contained now that a largely cosmetic “mini-deal” seems set to happen. Sure, the IMF came out with another downward revision to global growth this week, and yes, China’s Q3 GDP growth was, at six percent, its lowest in 30 years. But slowing growth is not new news, and it’s probably more a story for 2020 than for today. So what could go wrong?

Inversion Reversion

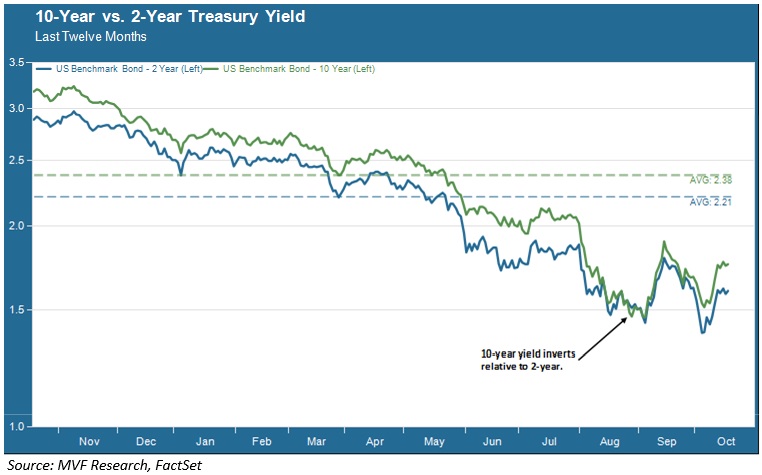

This week we look at the situation from another angle, that of the yield curve. Recall that back in August the inversion of the yield curve at the significant segment between 2-year and 10-year Treasuries was big news. A 2-10 inversion historically is a prescient harbinger of recession, and suddenly it seemed like we were barreling towards an imminent reversal of fortune in GDP growth. Or were we?

Look at that chart above, showing the trendline for the 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields over the past twelve months. Do you see the inversion? Can you make it out? Just follow the arrow…to that little dip at the end of August where, for a few days, the 10-year yield fell as low as 5 basis points (0.05 percent) below the 2-year yield. That was the dreaded inversion. And then it was no more. As of this week, some six weeks after the inversion began, the 10-year yields about 15 basis points more than the 2-year, which is also about where the average spread between the two maturities has been for the last twelve months.

Shades of 1998

So no inversion, no recession, right? Well, not for now. Just before the end of this month we will see how real US GDP growth fared in the third quarter. The consensus estimate is for a quarter-to-quarter gain of 2.2 percent – not fantastic, but not negative. If the consensus is more or less on target then – simply according to basic recession math – the earliest date on which the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research could call “recession” would be whatever day in April 2020 the Bureau of Economic Analysis releases its Q1 2020 GDP report. And for that to happen we would have to experience negative growth both in the fourth quarter of this year and the first quarter of next. Right now there is really nothing out there to suggest that today’s economy – for we are already in Q4 – is going to serve up negative growth.

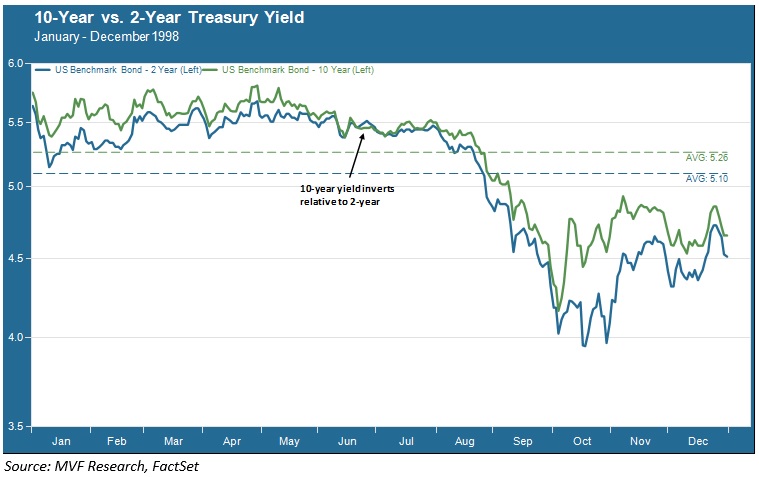

Here is another reference point. In the chart below we show the same graph as above – the 2-year and 10-year yield trends – for calendar year 1998. See if you can spot the similarity.

See that little inversion? In July 1998 the 10-year yield briefly fell below the 2-year. And throughout that year the spread between the two bonds was very tight – 16 basis points, very much like the 17 basis point spread we have seen in this calendar year 2019. As we now know, a recession didn’t happen in 1998, and one would not happen until 2001 (though the market started tanking a year before that).

Now, the economy of 2019 is not as strong as the economy of 1998 was (for proof, just look at the absolute value of the interest rates back then, ranging between four and six percent, compared to the sub-two percent trends of today). Global trade is under threat and businesses are investing less in their growth. But consumers are still spending, central banks are still printing money and ham-fisted political leaders are still groping for face-saving ways to get out of some of their more egregious missteps on the global stage (see: trade war, Brexit). The negatives will come back into sharper focus at some point. From where we sit, though, it seems less likely that the appointed hour will show up before this year winds down to a close.