There is a reason why we are constantly telling our clients that short-term movements in the market are unknowable. You know that some big piece of news is coming out in a couple days that could have major economic implications. You assume that prices of stocks, bonds and other assets will react accordingly, rationally, based on your assessment of whatever the news turns out to be. Then the news comes out, and the market reaction is completely different from those rational expectations you harbored. Welcome to the world of the short term, where everything is possible and all that is real melts into thin air.

Sell the Rumor, Buy the News

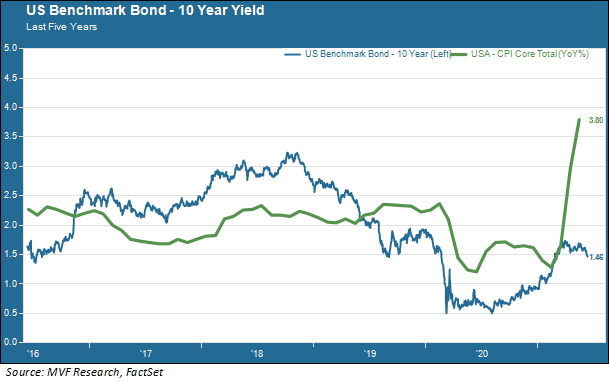

This week’s piece of news, of course, was the May report for the Consumer Price Index. The much-anticipated report, released Thursday morning, showed consumer prices rising five percent, year-on-year, with the core index excluding the more volatile categories of food and energy increasing 3.8 percent. The core CPI increase was the largest since June of 1992, twenty-nine years ago.

Now, one might think that the first casualty of an inflationary spike would be nominal bond yields, which would adjust upwards to compensate for the loss of purchasing power implied in higher consumer prices. What we got instead was the continuation of a rally in bond prices making this week the best performance for US Treasuries since the beginning of the year (remember that bond prices and yields move in inverse directions; i.e. an increase in prices means a decrease in yields.)

The chart below shows the five-year relationship between the core CPI and the 10-year Treasury yield.

Why don’t bond investors care more about this hotter-than-expected inflation report? Long-time observers of the market will turn to one of their favorite old saws: you sell the rumor and buy the news. If you look at the above chart, you will see that the 10-year yield (the blue line) started rising steadily in the second half of last year, and then really took off in the first couple months of this year. That was the “sell the rumor” stage. By the time the first really big jump in inflation happened, in April, the selling had largely played out. The big theme this week, even as the May number surpassed the April CPI, was that “inflationary expectations have peaked.” The news is confirmed, onto the next thing.

But For How Long?

Maybe the bond market is starting to actually believe what the Fed has been saying for months: that this bout of inflation is temporary and consumer prices are likely to peak sometime over the summer. There is some good evidence to support the Fed’s position. An unusually large component of this month’s price increase comes from sales of used cars. This reflects an unusual combination of factors: pent-up demand from consumers coming out of the pandemic with lots more household income to spend, and supply constraints from global supply chain disruptions and a worldwide shortage in semiconductor chips. The Fed’s reasoning is that these kinks will work themselves out without creating lasting structural problems.

They may be right. But their entire frame of reference is the economic growth cycle of the 2010s, characterized by modest increases in economic output, persistently low inflation and a continual need for easy monetary policy even years into what became the longest economic expansion on record. If we indeed are to go right back to that world then the Fed is doing all the right things now, buying $80 billion worth of bonds every month and keeping short-term interest rates at zero even while the economy runs at its hottest rate in several decades. The eye-popping inflation numbers we are seeing now will fade into oblivion and nobody will pay attention to the monthly CPI reports.

They may also be wrong. That chart above showing a 10-year yield of 1.46 percent and a core inflation rate of 3.8 percent doesn’t make any kind of sense in a world where that relationship becomes structural. Something would have to give – and that “something” would be the Fed’s easy money. With the end of easy money would come the end of the “Fed put” – the implied promise to bail out investors from sustained damage to asset prices. And that would be a very different world indeed.