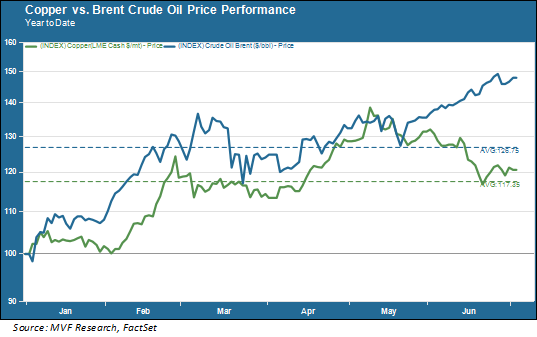

Commodities have been one of the big stories for the first half of this year. For much of this time so-called real assets from crude oil to copper to lumber rose together, benefitting from the tailwind of the reflation trade that also saw bond yields rise and stock market mojo switch from growth to value. Cracks in the reflation trade started to appear in May, as key industrial commodities including the aforementioned copper and lumber peaked. Oil, however, kept on keeping on. The chart below illustrates the diverging fortunes of crude and copper since mid-May.

A Really Weird Year (and Decade) for Crude

The persistence of oil’s strength has some traders betting that barrels of the viscous substance will hit $100 before the end of the year, a level not seen any time since before the great energy price plunge began in 2014. That would be one of the more remarkable comeback stories for any asset. Recall that as pandemic lockdowns got underway last year the price of crude oil plunged more dramatically than just about anything else. At one point near-term West Texas Intermediate crude futures actually traded below zero. “Take my crude…please!” went the refrain when a supply glut meant there was literally no place for a buyer to store the stuff.

At the peak of the pandemic one could have almost felt sorry for the oil producer nations that make up the so-called OPEC Plus group, which consists of the members of the old OPEC cartel, the scourge of the 1970s, along with Russia and other major producers. But the pandemic produced a couple developments that may make that elusive $100/bbl price more likely than not.

First, the group reached an agreement to cut production in April 2020, so that effectively it is sitting on about six million barrels per day of supply that remains in the ground rather than going to market. That agreement is currently up for discussion, which we’ll get to in a minute. The second development was a dramatic curtailing of investment in shale oil fields like the Permian Basin of west Texas. US-based unconventional production ramped up in the second half of the 2010s and was a major factor in keeping a lid on global prices. The pandemic hit these developers hard, and access to financing all but dried up. Even as the economic tea leaves pointed to a likely surge in demand on the other side of the pandemic, investors have been looking farther ahead to structural changes in the energy industry benefitting green technologies and discounting traditional fossil fuels. Permian’s loss is OPEC Plus’s gain, at least for now.

What Now?

Back to that 2020 production cut agreement. The OPEC Plus group was supposed to hammer out a deal yesterday that would, observers expected, see a gradual increase in daily production between now and the end of the year – perhaps in the area of 500,000 barrels per day (out of that total six million or so being held in the ground). The idea was to bring back enough production to help meet rising demand, but not so much as to significantly dampen prices.

The members failed to reach agreement yesterday, and are still at it as we write this today. Pushback from the United Arab Emirates and Russia, both of which would like to ramp up more production sooner, is holding back a final deal. At the same time other officials worry that if holding back production does succeed in getting to $100, that could change investor sentiment to finance and thus bring back more supply from the US shale fields, potentially eating into OPEC Plus market share and depressing prices. There is also the concern that the return of lockdowns around the world in response to the delta variant of the coronavirus could throw a wrench into near-term demand dynamics.

The Last Boom

However things play out in the short term, the longer-term outlook for fossil fuels is going to hinge mostly on the pace of transition from traditional energy sources to green technologies, a transition that is steadily gaining momentum. We wrote a few weeks ago about shareholder activism and regulatory directives affecting the exploration plans of major oil producer like Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell. The economics of technologies like solar and wind are improving and fast becoming cost-competitive alternative energy sources. While the dynamics of short-term supply and demand may be enough of a tailwind for crude prices to party like it’s 2014, the structural changes at play would suggest that there may not be too many booms left in the boom-and-bust cycle for this commodity.