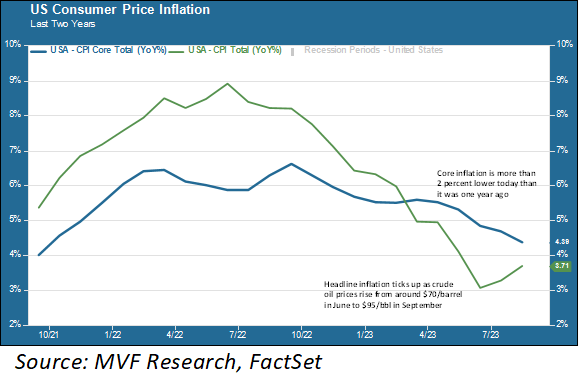

The Federal Open Market Committee will meet next week to determine whether to raise interest rates again. The broad consensus among those who pay attention to the FOMC’s doings is that they will not raise rates. The inflation measure the Fed pays attention to is more than two percent lower today than it was in September last year (4.39 percent compared to 6.64 percent, expressed on a year-on-year basis). That’s still more than two percent higher than where the Fed wants inflation to be, but it has been moving steadily in the right direction. Holding rates higher for longer will eventually get consumer prices back down to that two percent target level – that is what we expect to hear from Jay Powell next week.

Consumers Have Some Thoughts

So, about that inflation measure the Fed watches: it’s not the same one that we, the good American citizens and consumers that we are, have in mind as we go about our daily lives. It will likely come as no surprise to anyone reading this that gas prices are up, and up by a lot from where they were earlier this year. The price of gasoline is not included in so-called core inflation, which is what drives Fed deliberations on interest rates. Nor, for that matter, are food prices. So the two things that figure most directly into our weekly household spending are not part of the inflation equation that dominates the FOMC’s cogitating. And right now, these two different perceptions of inflation are moving in different directions.

Demand High, Supply Low

Typically, gas prices start to come down in late summer as vacationers return home and demand starts to fall. But prices at the pump started rising in a meaningful way in early July and have kept rising through and past the Labor Day weekend. While demand has remained somewhat higher than usual, the main reason for the spike in gas prices is that concerted supply cuts by Saudi Arabia and Russia have pushed crude oil prices to more than thirty percent higher today than they were in late June. The production cuts were initially announced to be a temporary measure, but this past week the Saudis and Russians confirmed that the production cuts would remain in place until at least the end of this year. That means about 1.3 million fewer barrels of oil per day than would be the case without the production cuts. This at a time when global demand for crude oil is set to reach a record 109 million bbl/day this year, thanks in large part to better economic growth than most economists expected at the beginning of the year.

The Expectations Game

Notwithstanding the Fed’s focus on core inflation, we expect there will be some discussion in the Eccles Building next week about gas prices – specifically, on the potential effect of continued higher prices on household inflation expectations. Inflation in large part is a game of expectations – households and businesses will shape their spending decisions around what they think prices will be next month and next year. This becomes a problem when expectations for higher inflation turn into a feedback loop. Businesses raise prices, workers demand higher wages and a wage-price spiral ensues.

So far this has not happened. According to this month’s University of Michigan Survey of Consumers, inflation expectations are in fact lower today than they were a month ago, with consumers expecting headline inflation (i.e., including those volatile food and energy categories) to be 3.1 percent a year from now. That’s down from the 3.5 percent one-year-forward expectation the consumers had in August.

Those expectations could change, though, if gas prices keep going up. If expectations for higher inflation become entrenched, it stops being a “headline inflation” problem and becomes a “core inflation” problem – and thus a problem for the FOMC and its interest rate decisions. For now, we are of the same mind as the broad consensus in expecting the Fed to wrap up on Wednesday without raising rates again. It wouldn’t hurt, though, to start seeing some lower numbers as we drive past those gas station signs on our way to and from work.