The Fed intends to keep interest rates at or close to zero for the indefinite future. The central bank has said as much in each of its last several meetings of the Open Market Committee that sets monetary policy. But it is important to remember that while the Fed has direct influence over short-term interest rates through its management of the overnight Fed Funds rate, it has less control over what happens further out on the yield curve. Once you get into the intermediate-maturity range beyond five years or so, interest rates are subject to a variety of supply and demand variables both domestic and global.

Infrastructure and Bonds

Last week we talked about the possible return of the so-called “infrastructure-reflation trade” and the role it could play as a catalyst for an equity market rotation out of the long-dominant, very expensive growth stocks and into some of the cyclical sectors that feature more prominently in value stock indexes. This week we will focus on what such a development could mean for the bond market. Remember that when the yield on a fixed income security goes up, the price of that security goes down. When we make decisions about the fixed income asset classes in the portfolios under our management, we have to take into account the likely effects of different scenarios on different maturities and bond types. Given that short-term yields are unlikely to change much under the Fed’s standing policy, one key focus for us this year will be on what could increase spreads between shorter-term and longer-term rates.

The Long and the Short of Things

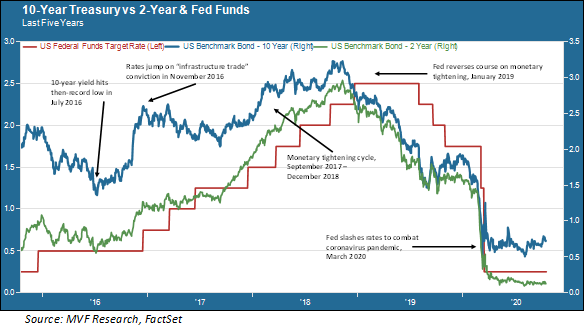

In the chart below you can see the relative movements of three key benchmarks: the 10-year Treasury yield, the 2-year Treasury yield and the Fed Funds rate, the rate at which banks lend to each other overnight and over which the Fed exerts direct influence through its monetary policy operations.

As you can see from the chart, quite a lot has happened in the bond market over the past five years. We show that in July 2016 the 10-year Treasury yield reached a then-record low of 1.36 percent. When we say “record low” we mean “never before in the history of global bond benchmarks.” The 10-year Treasury is essentially a worldwide reference point for the “risk-free asset” standard against which the risk properties of all other assets are evaluated. Never before since such things have been calculated had the global reference point been that low.

But just four months after reaching that low point, the 10-year yield shot up immediately after the 2016 election which, as you will recall from our commentary last week, was the catalyst for the infrastructure-reflation trade. The sharp rise in yields reflected the belief that a massive dose of public spending would require a large increase in Treasury bond issuance to fund the different programs. Investors would demand higher rates to compensate for the presumed risks inherent in the rise of the national debt.

You Take the High Road, I’ll Take the Low Road

As we all know, that major infrastructure program never happened. But in 2017 rates rose for a different reason: the Fed got serious about the tighter monetary policy that it had put on hold after the stock market pullback in early 2016. Short term rates rose in more or less linear fashion along with the Fed funds rate, while the 10-year rate also rose but in a manner less closely correlated to Fed policy moves.

All of which brings us to the very strange world of fixed income in 2020. The 10-year yield crashed through that earlier all-time low of July 2016, bottoming out around 0.5 percent in the immediate wake of the general market panic in March and rediscovering those lows in August. Overall, the bond market has been a relative sea of calm during this period after the Fed pledged a variety of liquidity measures to support bonds of all stripes from Treasuries to investment grade corporates and even junk bonds.

But the Fed has pointedly not done one thing: it has not endorsed a policy of direct intervention in maturities downstream from the Fed funds rate. “Yield curve management” is the term of art for this kind of direct intervention, and the central bank did use it once before, during the Second World War. Moreover, while the topic of yield curve management has been up for discussion at recent FOMC meetings, the maturity bands concerned would likely be limited to the 2-3 year range.

That leaves longer maturities subject to unpredictable market forces, including – again – the possibility of a real infrastructure spending program if the Democrats win big in November. Joe Biden elaborated on this topic in some detail during his town hall meeting last night. Looking at where the 10-year is today in the above chart, and looking at its trajectories over the past five years, it seems that there is plenty of room for upside movement in the months ahead. Specifically, it appears plausible that the spread between the 10-year and short-term rates could widen, and possibly widen considerably.

None of this is a given, of course. We can’t even be certain that the Fed would leave longer-term rates to the fates of the market without intervention if rates were to rise beyond a certain level. Nor is anything related to the election and its aftermath predictable in any statistically meaningful way. But we have to consider the potential scenarios arising from this sea of unknowns and make provisions accordingly. A widening of maturity spread is, if nothing else, an alternative with not-inconsequential probability.