We sometimes refer to productivity as “the most important macroeconomic data point that nobody pays attention to.” That’s in contrast to the holy trinity of jobs, inflation and GDP growth, the three reports that generate the most chatter among financial media types. The productivity report for the first quarter came out yesterday, but unless you were deep into the economics pages of the Financial Times or the Wall Street Journal, its coming and going would have passed you by. That’s a pity, because in the long run our economic prosperity depends on growth, and in our demographically challenged times, the only path to sustainable growth runs through productivity. The population growth rate is in decline, and with a growing ratio of deaths to births, the percentage of the population in peak working-age years is declining. Either we grow through increased productivity, or we don’t grow – it’s that simple.

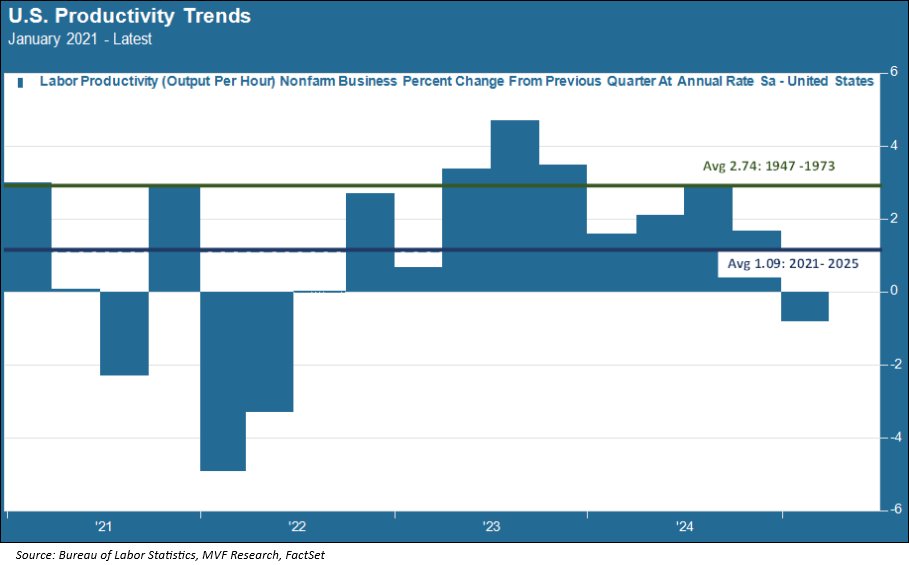

With that in mind, it wasn’t great to see productivity decline in the first quarter by a greater than expected minus 0.8 percent (annualized) from last year’s fourth quarter, marking the first quarter of negative growth since 2022. Let’s take a big picture look at how we got from earlier economic cycles to where we are today.

Making More with Less

There are several technical definitions for productivity, but the underlying concept is always the same: making more stuff with less expenditure of effort, time and money. The importance of this metric was one of the key insights Adam Smith described in his seminal 1776 tract “The Wealth of Nations,” explaining how a pin factory could massively increase its daily output through the implementation of specialized labor processes. That was in the earliest years of the Industrial Revolution; one hundred years later, the manufacturing enterprises of Great Britain and the United States were achieving productivity gains at a rate commensurate with Smith’s pin factory on steroids.

Productivity in the US continued to grow at a brisk clip through much of the twentieth century. After the Second World War the Bureau of Labor Statistics started measuring productivity gains, and through the first quarter century of so after the war, the average rate of productivity growth from quarter to quarter was around 2.7 percent (annualized). US manufacturing dominated the world, and organizations learned how to optimize their production processes at a scale that would have been previously unimaginable.

Productivity growth started to fall off sharply in the early 1970s, though, and apart from a brief resurgence in the early 2000s (largely seen as the impact of Information Age innovations), it has lagged ever since. The chart below shows that from 2021 to the present, the average growth rate was just 1.09 percent. That is more than two and a half times less than that 2.7 percent growth rate from 1947 to 1973.

Is AI the Answer?

What’s the recipe for improving productivity? Opinions vary among economists. There is one school, perhaps best represented by Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon, that deems it unlikely we will ever see the kind of productivity growth we enjoyed in the middle years of the last century. In his book “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” Gordon argues that the productive power we got from the critical inventions of electricity and the internal combustion engine are unlikely to ever be repeated, and we’ve already squeezed as much as we can out of those.

Others, however, point to the observed fact that there is usually a time lag between a new invention and that invention’s translation to commercial gain. Consider electricity; it was invented in 1879, but in 1919, forty years later, only half of American houses were connected to the grid. More recently, semiconductor chips had been around for more than forty years before we saw that brief Information Age productivity surge in the early-mid 2000s.

With this in mind, perhaps it is not surprising that many of the productivity optimists among us today point to artificial intelligence. After all, it has been a scant two years since ChatGPT burst onto the scene, launching a public fascination with AI and, of course, the stock market craze that drove much of the upside in those two back-to-back 20 percent-plus years on the S&P 500 in 2023-24. We know that, despite all the excited chatter, less than ten percent of all businesses claim to have AI-driven processes deep into their business models. Perhaps it will just take a bit more time before the effects show up in the productivity numbers. It would be nice to think so, because the growth isn’t going to happen all by itself – and it isn’t going to happen from whatever is passing for economic policymaking in Washington these days.