Rate hike chatter is back front and center in the wake of this morning’s relatively strong jobs numbers. Payroll additions exceeded expectations while hourly wages, which historically correlate closely with Fed policy, also ticked up ahead of consensus. Today’s data do not make for a complete picture, and the Fed will probably wait to digest the Q2 GDP release before putting a definitive mark on the rate hike calendar. But it is fair to say that the odds of September-time frame action have improved with today’s release.

So we have a potentially volatile cocktail made up of the Fed, Eurozone bonds gone wild, and an expensive, sideways-trading stock market looking for direction. Are these the ingredients for a hefty pullback in US stocks? We would not rule out the possibility. We would also not be inclined to run for the hills were such a pullback to happen. A brief look at market history will explain why.

Pullbacks, Bulls and Bears

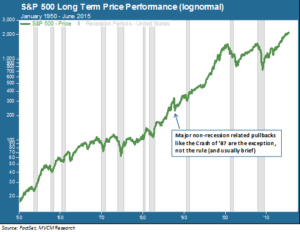

A reversal of 5 percent or more in the stock market is a headline-grabbing event, engendering a climate of fear. Most of the time, though, the fear is overblown. We define a “pullback event” as a reversal of 5 percent or more, followed by a recovery of 5 percent or more. Since 1950 there have been 177 such pullback events on the S&P 500, or about one every four and a half months on average. Occasionally the pullback led to a broader bear market environment, notably in the double recessions of the early 1970s, the 2000-02 tech collapse and then the Great Recession of 2008-09. Most pullbacks, though, were relatively shallow and brief. The chart below illustrates the price performance of the S&P 500 since 1950, with the vertical grey bands indicating US economic recessions.

What this chart illustrates is that major pullbacks outside of recession-related bear market environments are anomalies. The most severe of these anomalies was the Crash of 1987, when US stocks dropped more than 20% in a single day. The events which drove that crash were largely unrelated to prevailing economic fundamentals, and would have been very difficult to predict ahead of the event. As deep as that reversal was, though, shares had recovered their losses and set new highs within one year. In a similar vein, markets tumbled on two non-recession related occasions in the 1960s and once in the latter stage of the 1990s bull market. Since the 2009 market bottom there have been two relatively significant events – a 16 percent reversal from April to July in 2010, and a 19 percent drop from July to October in 2011. Even in the latter instance, though, the market bounced back to a new high just three months after hitting bottom.

Growth Does Not Cause Bear Markets

So what does all this mean for today? Isn’t it possible that a pullback sometime this summer or fall could lead to a larger bear market? It is possible, of course. There are thousands of variables at play in the market every day, any combination of which could potentially bubble up to the surface at any time, cause havoc and eventually drag the economy into recession. What we think highly unlikely, though, is that a rate hike per se would usher in a prolonged period of misery. If a rate hike happens, it will happen because the Fed is convinced that underlying economic growth is strong enough to merit a rate hike. And economic growth is not a catalyst for a bear market.

Yesterday, IMF head Christine Lagarde warned the Fed not to raise rates in 2015, citing “too much uncertainty” in the global environment and darkly opining that the Fed’s credibility would be on the line if it were to unwisely move ahead. We understand the sentiments driving Mme. Lagarde’s comments, but believe they are misplaced. The Fed’s mandate is to guide US monetary policy towards the objectives of stable prices and full employment. It is not to placate jittery market sentiment around the world. If the data suggest that a measured rate hike is the appropriate policy for this mandate, then that is the right thing to do. Have faith in markets to adjust accordingly.

And if stocks do freak out and retreat by 5 or 10 percent? More likely than not, that would be welcome news for opportunity-starved value investors, ourselves included.