Few pronouncements strike as much dread into the hearts and minds of investors as those ominous three words: “yield curve inversion.” When yields on bonds with longer maturities fall below those with shorter time horizons, there’s a reasonable chance that a recession is on the way – at least according to the data going back many decades. As always, though, there are caveats to the “inversion therefore recession” logic. False positives have occurred, most recently when the 10-year and 2-year Treasury notes briefly inverted in September 2019. That fleeting inversion was in fact followed by a recession in March 2020, but that recession was a deliberate decision to turn off the entire economy based on an event nobody knew anything about in September 2019.

Et Tu, Six Month Bill?

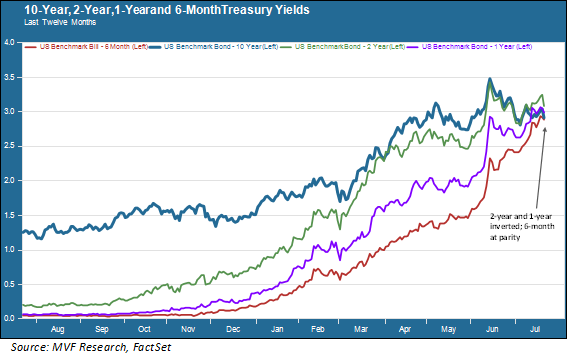

False positives aside, the current shape of the yield curve really does look like the bond market expects a recession to show up in the not-too-distant future. Not just the 2-year, but the 1-year and even the 6-month Treasury bill are now inverted to the 10-year note. The 6-month was at parity with the 10-year based on yesterday’s close (see chart below) but in early morning trading today the yield on the 6-month is 2.86 percent versus 2.77 percent for the 10-year note.

Interestingly, the compression in longer-dated maturities has been having a mostly positive effect on the stock market this week, particularly the growth-oriented parts of the market that benefit more from lower interest rates. The 10-year Treasury is widely used as a benchmark for calculating a firm’s cost of capital, so when that rate goes down, the firm’s value goes up. Over the past several weeks growth stocks, which suffered the brunt of the stock market’s pullback earlier this year, have outperformed their value stock counterparts by a substantial margin.

It’s Worse In Other Places

Part of the explanation for the inverted curve, though, may have nothing to do with any recession potential and a great deal to do with the fact that things in other parts of the world are worse than they are here at home. The US dollar has risen sharply against other major currencies including the euro, the British pound sterling and the Japanese yen, at times rising to levels not seen in more than 20 years. A stronger dollar increases the attractiveness of US assets. Intermediate and long-term Treasury securities are a core holding for foreign central banks and financial institutions.

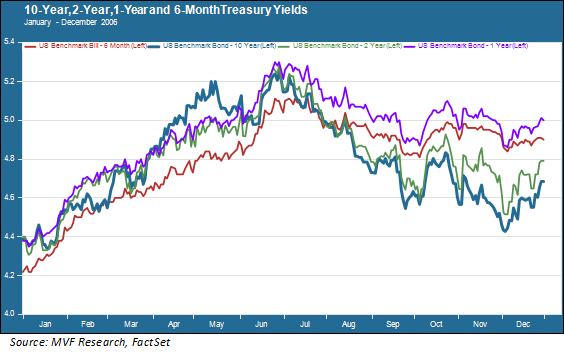

In fact, one of those “false positive” moments for inverted yield curves happened during another instance of monetary tightening by the Fed. In 2006 then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke expressed puzzlement as to why the 10-year yield was lower than those of the shorter maturities. The chart below is a replica of the one above for the period from January to December 2006, and you can see that the inversion lasted for the better part of that year’s second half.

The answer to Bernanke’s puzzlement turned out to be massive demand for intermediate and long US Treasuries by foreign institutions, above all China’s central bank for purposes of foreign currency reserves. Today, with China in seemingly perpetual Covid lockdown, Europe dealing with a full plate of social, political and economic crises, and threats of more emerging market debt defaults following Sri Lanka’s lead, the case for US Treasuries would appear likewise strong.

Maybe Yes, Maybe Mild?

The probability of some flavor of recession in the next six months is almost certainly north of zero, and perhaps well north. But there is almost nothing in the current batch of macroeconomic data to suggest that if one were to occur it would be of the gut-wrenching variety like 1980 or 2008. A more likely comparison would be 2001, when the economy was technically in recession for eight months but never even saw two consecutive quarters of negative growth. A mild recession may well be the price to pay for bringing inflation down. That would be preferable to, say, avoiding recession entirely but living with a protracted period of slow growth and high inflation similar to the 1970s.

And maybe that outcome is, in fact, what the bond market is signaling. Credit risk spreads between Treasuries and lower-rated investment grade corporate securities have risen slightly in recent weeks but are still below their three-year averages, suggesting that fears of an approaching wave of corporate defaults are not present. We will see more pieces of the puzzle come together in the coming weeks with the release of Q2 GDP and the bulk of earnings reports from major S&P 500 constituents. For now, though, the strange shape of the yield curve is not telling us to run for the hills.