This week we found out that US labor productivity – the output of goods and services per hour worked – of nonfarm workers fell by 1.9% for the second consecutive quarter, bringing the 5 year average to a measly growth rate of only 0.65%. This information comes on the tail of last week’s disappointing news that the economy grew at a mere 0.2% during the first quarter (just an initial estimate – but still). “Fret not!” says Positive Polly – we had another rough winter this year which is probably why the GDP numbers are less than stellar. Labor productivity will increase in time. And unemployment is the lowest it’s been since May 2008!

Indeed, the fundamentals don’t look terrible – the recent jobs numbers have been mostly promising, and (with the exception of Q1) GDP was positive in 2014. But what will it take to return to growth comparable to – or even half as robust as – we saw during the 1990s?

Working 9 to 5

The workforce would seem to be steadily increasing. New jobs have been added every month since September 2010 and, while not at levels pre-financial crisis, the unemployment rate is at a respectable 5.4%. However, there is a dark underlying truth: we have an aging workforce, slowing population growth and (as per the trend described above) slowing productivity. By 2020 approximately 25% of the workforce will be at least 55, and most baby boomers cite their optimum retirement age at 66. This means that by 2030 the majority of baby boomers will no longer be working, and the population hasn’t been increasing enough to support a one for one replacement for this large portion of the workforce. Many women are waiting longer to have children – in 1970 the average age of first time moms was 21 and by 2008 it had increased to 25.1. The birth rate has declined every year since 2007.

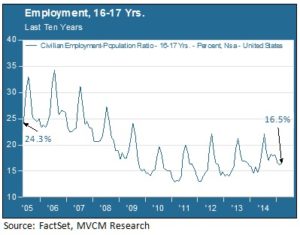

Gen Z Bails on After-School Jobs

Another trend working against labor participation growth is at the young end of the labor pool. After-school jobs have become less en vogue with high schoolers, who in other times took on a variety of jobs by way of introducing themselves to the work force. Employment among 16-17 year olds is lower today by 7.8% from its level in 2005. More teenagers are pursuing higher education (census data estimates that only 28.8% of baby boomers earned a bachelor’s degree or higher) and after school work is taking a backburner to SAT prep courses and other pursuits deemed more likely to impress college admissions offices. So not only is the younger generation dropping its after-school jobs, it is also delaying its entrance into the workforce. That also skews the average workforce age higher.

Productivity Slowdown

A declining rate of workforce and population growth leave productivity as the only viable path to a faster-growing economy. So we need to pay close attention to what has caused our labor productivity to slow down for the past 5 years. The easy answer would be that the financial crisis is the root of all our productivity problems. But let’s not forget that the recession ended in July of 2009, and even with the combination of a growing workforce and below-trend wages, productivity is still suffering. One reason for this could be due to the fact that companies have prioritized giving money back to shareholders (mostly in the form of dividends and share buybacks) over investing into their businesses. This trend has intensified since 2009. As the old saying goes, you have to spend money to make money. Unless businesses find new ways to invest in and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their process flows, it may be tough to move that productivity dial much.

Other economists argue that productivity slowed when the technology boom of the 1990s ended, which would signify a much more concerning growth problem in the US. Innovation in the 1980s and 90s saw workplace productivity improve immensely, fueled by adaption of successive Information Age technologies like the PC, client-server networks and Internet 1.0. Now, innovation is not dead – cloud computing, social media and 3D printing are just a few of the technologies which have disrupted traditional industry structures since the dawn of the millennium. So where are the productivity benefits? Perhaps the dynamics of modern consumer markets have contributed to a discord between innovation and efficiencies. Or perhaps we have all grown too impatient, and the productivity gains from recent innovations will show up eventually.

Since the end of the financial crisis, most investment assets have grown at a robust clip. Wages, consumer prices and other economic growth measures have lagged. This is not a recipe for sustainable economic success. We should be mindful of how the productivity trend develops – for therein lies the most plausible key to real growth.