Some foreign words don’t have English translations that do them justice. Take the German “Schadenfreude,” for example. “Delight at the expense of another’s misfortune” just doesn’t quite pack the same punch. The Russian word “smutnoye” also defies a succinct English counterpart to fully import its meaning. Confusion, vagueness, a troubling sense that something nasty but not quite definable is lurking out there in the fog…these sentiments only partly get at the gist of the word. Russians, who over the course of their history have grown quite used to the presence of a potential fog-shrouded malignance out there in the fields, apply the term “smutnoye” to anything from awkward social encounters, to leadership vacuums in government, to drought-induced mass famines.

Who’s In Control?

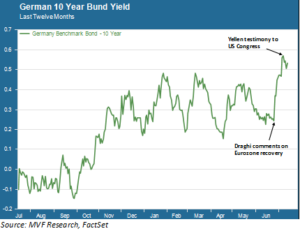

We introduce the term “smutnoye” to this article not for an idle linguistic digression but because it seems appropriate to the lack of clarity about where we are in the course of the current economic cycle, and what policies central banks deem appropriate for these times. Recall that, just before the end of the second quarter, ECB chief Mario Draghi upended global bond markets with some musings on the pace of the Eurozone recovery and the notion that fiscal stimulus, like all good things in life, doesn’t last forever. Bond yields around the world jumped, with German 10-year Bunds leading the way as shown in the chart below.

At the time we were skeptical that Draghi’s comments signified some kind of sea change in central bank thinking (see our commentary for that week here). But bond yields kept going up in near-linear fashion, only pulling back a bit after Janet Yellen’s somewhat more dovish testimony to the US Congress earlier this week. And it has not just been the Fed and the ECB: hints of a change in thinking at the apex of the monetary policy world can be discerned in the UK and Canada as well. The sense many have is that central bankers want to wrest some control away from what they see as an overly complacent market. That, according to this view, is what motivated Draghi’s comments and what has credit market kibitzers focused like lasers on what words will flow forth from his mouth at the annual central bank confab in Jackson Hole next month.

Hard Data Doves

In that battle for control, and notwithstanding the recent ado in intermediate term credit yields, the markets still seem to be putting their money on the doves. The Fed funds futures index, a metric for tracking policy expectations, currently shows a less than 50 percent likelihood of a further rate hike this year, either in September or later – even though investors know full well that the Fed wants to follow through with one. Does that reflect complacency? A look at the hard data – particularly in regard to prices and wages – suggests common sense more than it does complacency. Two more headline data points released today add further weight to the view that another rate hike on the heels of June’s increase would be misguided.

US consumer prices came in below expectations, with the core (ex food & energy) CPI gaining 0.1 percent (versus the expected 0.2 percent) on the month, translating to a year-on-year gain of 1.7 percent. Retail sales also disappointed for what seems like the umpteenth time this year. The so-called control group (which excludes the volatile sectors of auto, gasoline and building materials) declined slightly versus an expected gain of 0.5 percent. These latest readings pile on top of last month’s tepid 1.4 percent gain in the personal consumer expenditure (PCE) index, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, and a string of earlier readings of a similarly downbeat nature.

Why Is This Cycle Different from All Other Cycles?

In her testimony to Congress this week, Yellen made reference to the persistence of below-trend inflation. The Fed’s basic policy stance on inflation has been that the lull is temporary and that prices are expected to recover and sustain those 2 percent targets. But Yellen admitted on Wednesday that there may be other, as-yet unclear reasons why prices (and employee wages) are staying lower for longer than an unemployment rate in the mid-4 percent range would normally suggest. This admission suggests that the Fed itself is not entirely clear as to where we actually are in the course of the economic recovery cycle that is in its ninth year and counting.

Equity markets have done a remarkable job at shrugging off this lack of clarity. Perhaps, like those Russian peasants of old, they are more focused on maximizing gain from the plot of land right under their noses while ignoring the slowly encroaching fog. Perhaps the fog will lift, revealing reason anew to believe a new growth phase lies ahead. All that remains to be seen; in the meantime, “smutnoye” remains the word of the moment.