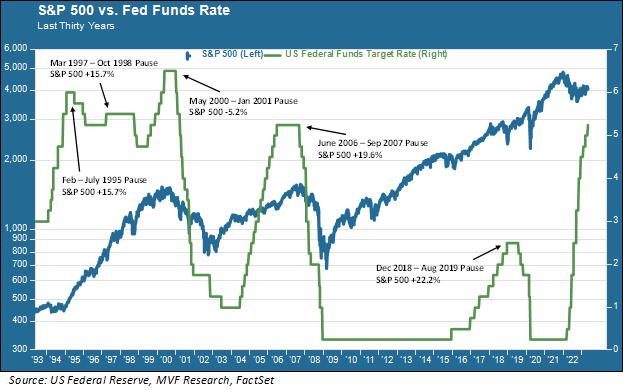

Last Wednesday, Fed chair Jay Powell strongly suggested that the 0.25 percent rate hike the FOMC voted for that day would be the last one for some time. We now find ourselves – probably, because nothing is certain – in a pause period after a prolonged series of rate hikes for just the sixth time in the past thirty years. What does that mean? If you tune into CNBC or one of the other financial-news-as-sports media sites you will probably encounter panels of talking heads telling you what the market “does” when the Fed pauses after a monetary tightening program.

If you are a longstanding reader of our weekly column, of course, you will not be surprised when we make the case that every time is different, because the circumstances are different, and also that a sample set of five prior observations in a thirty year period falls way short of statistical significance. That being said, it can be useful for context to have a perspective on past events. So here goes.

Variable Timing

One thing you can easily see from the above chart is that there is no particular fixed amount of time that rates spend in the pause position. The shortest pauses in this 30-year period were the six months time-out in 1995 and the eight month wait-and-see in 2019. As we will discuss further below, this is an interesting comparison because of a similar motivation for the rate cuts that took place in October 1995 and August 2019.

The pause periods that began in 1997 and 2006, by contrast lasted more than a year. This is a useful thing to keep in mind when we look at what is going on in the bond market today. As we have noted in recent columns, bond investors remain confident that the Fed will start cutting rates as soon as June or July. That seems out of line with historical observation; if the Fed were to announce a rate cut at, say, the July 26 FOMC meeting then it would constitute the shortest pause in the past thirty years. What gives the bond market so much confidence in this scenario?

Insurance Cuts

Perhaps the bond market is thinking about those 1995 and 2019 pause periods in coming up with an abbreviated schedule for the current one. When the Greenspan Fed began raising rates in early 1994, it was interested in demonstrating its inflation-fighting credibility. The rate hike in February of that year took the market by surprise, causing a sharp but brief drop in equity markets. The decision to begin cutting rates in July 1995 was seen as an “insurance” move; in other words the FOMC was satisfied with where inflation was at the time and sought a bit of pre-emptive insurance to protect against a possible recession. Of course, the recession never happened, and instead the second half of the 1990s was one of the strongest economic growth periods ever.

In 2019 the thinking by the Powell Fed was somewhat similar. You may recall that in late summer of that year the yield curve was flattening (it would actually invert for a very brief period in September). Inflation was well contained within the Fed’s two percent target, so the FOMC didn’t see much downside to a little monetary stimulus in case a slowdown turned into a recession.

The problem with using 1995 and/or 2019 as a guideline for 2023, of course, is that inflation today is in a very different place. We got another reading this week with the April CPI report, and while it continued to show moderating price growth, the fact is that inflation remains well above the Fed’s target and most economists envision a longer period before we see a return to a sub-three percent CPI.

Pause Before the Storm

Then there are the other times when the pause period ended, not because of recession insurance but because the fire was already raging. In 1998 the motivating factor was the Russian debt crisis that led to the collapse of a systemically connected hedge fund, Long Term Credit Management. In 2001 the collapse in tech stocks was already well underway and dragging the real economy down with it. September 2007 was when a number of short-term credit markets seized up, prefiguring the total meltdown that would happen the following year. And in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic shut down the global economy.

One of the points we have been arguing throughout this year is that we envision a relatively mild cyclical recession happening sometime in the not too distant future, with the “mild” adjective dependent on the absence of some external shock to the financial system. Those external shocks are what precipitated the deep cuts of 2001, 2008 and 2020. If we get a similar seismic event this year then, yes, we imagine that playbook will be put to use this time as well. If we don’t get such an event, which is certainly what we hope, then we do not see where the case for a summertime rate cut materializes.

As for what can be expected in the way of stock market returns? Take your pick. The S&P 500 delivered double-digit gains in four out the five previous pause periods. For entirely different reasons each time, none of which have any real relevance for today. Que sera, sera.