The ancient Chinese concept of “wu-wei” roughly translates to “achieving without action.” It was a quality sought in great leaders, who were to understand that a successful outcome – to a military campaign or overthrowing a bandit rebellion or whatever – was not due to aggressive individual actions but to patient non-action until the celestial alignment of circumstances proved to be most propitious to the task at hand.

The Fed has been practicing its own form of wu-wei for some months now, backing off from taking any direct action that might undercut the natural cadence of economic growth arising from its last bout of monetary intervention last March and the more recent fiscal tailwind expected to proceed from the Biden administration’s pandemic relief program currently making its way through Congress. Could the economy run a bit too hot and spark a surge in consumer prices? Sure – but that is perfectly okay after so many years of below-trend inflation, says the Fed. Let animal spirits run awhile and the natural course of things will eventually reveal itself to us. The spirit of Sun Tzu and Lao Tse lives on.

Taperless Turmoil

The bond market, to put it mildly, does not share the Fed’s serene demeanor. Prices in government bond markets around the world dropped this week and yields soared as investors focused ever more closely on the potential for inflation to come roaring back in the second half of the year, if not sooner. The 10-year Treasury yield, the most widely used proxy for the risk-free rate that underpins valuations of just about every type of asset, traded as high as 1.6 percent in Thursday trading. The same 10-year note started this year with a yield of just 0.9 percent.

While that may not seem like much of a movement, it represents an extraordinary level of volatility for what is supposed to be the world’s safest asset class. Think of it this way. A movement from 0.9 to 1.6 represents a rate of change of 78 percent. Imagine if the Dow Jones Industrial Average changed from its current level of around 31,000 either up or down by 78 percent. That would imply a point change of 24,000! News anchors go breathless when the Dow goes up or down by 500 points, let alone tens of thousands. Such is the often unappreciated importance of seemingly small moves in bond yields. Such also is the importance of paying attention to rates of change, not actual point differences (something the financial media is chronically incapable of doing when it comes to the Dow).

Way back in May of 2013, then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke mused one day about the possibility of a “taper” in the quantitative easing program of monthly bond purchases. Bernanke didn’t say the Fed was definitely going to taper – he was just floating a thought out loud. What happened next was a major freak-out in the bond market quickly dubbed the “taper tantrum” as investors feared that without the assurance of liquidity from the Fed, demand would falter and rates would rise.

There is no talk of a taper today – in fact there is no talk of doing anything (hence our slightly obscure invoking of the wu-wei idea in the opening paragraph). That’s the problem, as far as bond investors are concerned. Here’s why. Asset markets of all flavors have come to expect that the Fed will always be there to provide liquidity and bail them out (institutional investors may hate the concept of socialism, except when they themselves are its beneficiaries). By this logic, the natural course of action for the Fed would be to declare itself averse to higher intermediate and long-term interest rates, and at least hint that they would enter those markets with targeted bond-buying programs to keep rates down (the Fed’s existing bond-buying program is concentrated at the shorter end of the yield curve).

Is There a Tipping Point?

Here is where the concern in the bond market starts to tip into riskier financial assets like common equities. If the Fed is truly content to sit back and watch intermediate and long-term interest rates rise further, there is potentially a tipping point where those higher rates have a real effect on stock price valuations. All else being equal, higher rates depress the value of future cash flows that factor into share price calculations. The more uncertain and farther away from the present the cash flows are, the more negatively they are affected by rising rates. That is one reason why value stocks have opened up a wider performance gap versus growth stocks in recent weeks.

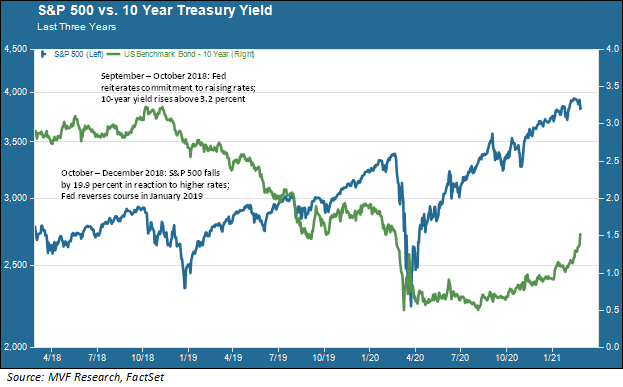

So where is that tipping point? Nobody knows, but here is one reference point. In September 2018 the Fed reiterated its commitment to continue raising interest rates, and the 10-year yield topped 3.2 percent in early October. That marked the beginning of a near-20 percent slide in stock prices that ended only when the Fed capitulated in January 2019 and announced it would be reversing its monetary tightening.

Is 3.2 percent the tipping point? Nobody knows. A great many things have changed in the world since 2018. And 3.2 percent is still double the level of the 10-year today. What we do know is that in 2018 the bond market, and then the stock market, forced the Fed to back off from its policy course so as to minimize market disruption. All that we’re hearing from the Fed today is crickets – no action planned and stated satisfaction with the current state of monetary and fiscal policy as tailwinds to the economic recovery. The bond market is having a very hard time with this sanguine posture. “Bond vigilantes” – a term hardly in use at all since the 1990s – seem to be out there again, warning of the danger posed by high inflation, while the Fed would prefer to see higher rather than lower inflation.

Again – just to be clear, there is no actual surging inflation today. We cannot estimate how much inflation there will be even after the expected rise in consumer demand this summer. And, most importantly, we do not have any evidence at all that inflation arising from a temporary demand spike will be anything other than a one-off phenomenon. The bond market, along with the surging market for basic commodities, may be way out ahead of its skis. Or it may be an accurate read of future price trends. Either way, however, this continues to be a good time to keep one’s bond portfolio tethered to shorter durations in higher quality securities.