Like most of our fellow investment practitioners, we subscribe to a variety of daily market digests – those couple paragraphs at the market’s opening and closing bell that purport to tell us what’s up, what’s down and why. A brief summary of these digests over the course of 2017 might go something along the following lines: la la la la TAXES la la la la TAXES la la la…you get the picture. Not corporate earnings, certainly not geopolitics – nothing, it would seem, has the power to capture Mr. Market’s undivided attention quite the same way as potential changes to our tax code.

Well, this week is one of those times where the subject is front and center as Congress attempts to set the process in motion for some kind of tax “reform” before the end of the year. As we write this, more information is coming out about what the legislation may, and may not, ultimately include. We should note that it is far from certain that anything at all will be accomplished within this year. Taxes affect everyone in some way – individual and institution alike – and literally every item on the table will have its share of vocal backers and opponents. Over the coming weeks we will share further insights on these developments; our purpose today, though, is to consider at a more fundamental level the relationship between taxes, economic activity and markets.

Taxes and Growth

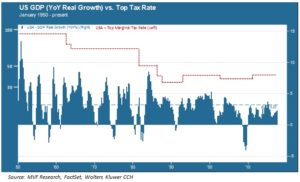

One of the central motivations for just about any attempt at tax reform is to stimulate economic growth. There are plenty of competing ideologies about this – and it matters for purposes of the discussion whether we are talking about the short term or the long term. But one reasonable question to ask would be how relevant a factor tax rates have been as an influencer of growth over the long term. The chart below illustrates year-on-year GDP growth in the US since 1950, along with the top marginal (individual) tax rate over the same period.

Top tax rates on wealthy individuals were very high – 91 percent in the 1950s and a bit lower (77 and then 70 percent after 1964) before coming down to 50 percent in the first wave of Reagan-era tax reform in the 1980s. Subsequently they have fluctuated between the high and the low 30s through the successive policies of the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations. What conclusions could be drawn from the impact of alternative tax regimes on long term economic growth? In our opinion only one; namely, that any correlation between marginal tax rates and growth is very weak, at best. The high rates of GDP growth in the 1950s and 1960s took place neither because of nor in spite of high taxes, but for a whole host of other reasons based on global economic conditions at the time.

The same could be said when considering the economic growth spurt of the 1990s, after the Clinton administration had raised taxes in 1993: the growth happened because of many different variables at play, and taxes were at best a peripheral consideration. It is particularly important to keep this absence of causation or even correlation in mind when we are told by policymakers that any revenue lost from tax rate reduction will pay for itself from higher growth. That’s ideology – but the numbers simply aren’t there to back it up, and not for lack of ample data.

Taxes and Earnings

Individual tax rates are only part of the equation, of course. A big part of the market’s focus this year has been on corporate taxes. The statutory US corporate tax rate of 35 percent is high by world standards, so the argument goes that reducing this rate to something more competitive (with 20 percent being the number floated in the current version of the plan being floated by Congress) would be a powerful catalyst to grow US corporate earnings. How does this claim stack up?

At one level the math is fairly simple. Earnings per share, the most common number to which investors refer to measure the relationship between a company’s profits and its stock price (expressed as the P/E ratio), is an after-tax number. If Company XYZ paid 35 percent of its operating profits to the tax man last year, but this year Uncle Sam only gets 20 percent of those profits, then the other 15 percent is a windfall that goes straight to the bottom line (to be retained for future growth or paid out to shareholders at the discretion of Company XYZ’s management). That growth – all else remaining equal – will make XYZ’s shares seem more reasonably priced, hence, good for investors.

There are two things to bear in mind here. First, that tax windfall happens only once in terms of year-on-year growth comparisons. Once the new rate sets in, XYZ will get no future automatic tailwind from taxes (i.e., EPS growth will then depend on the usual revenue and cost trends that drive value). Second, the potential ongoing benefits from the lower tax rate (e.g. a larger number of economically viable investment projects) will depend on many factors other than the tax rate. It’s not irrelevant: taxes do figure into net present value and weighted average cost of capital, which in turn are common metrics for go / no-go decisions on new projects. But many other variable are also at play.

The other issue with regard to the statutory tax rate is that it is a fairly poor yardstick for what most companies actually pay in taxes. The mind-numbing complexity of the US tax code derives from the many deductions and loopholes and credits and other goodies that influential corporate lobbyists have won for their clients over the years. The influence of these groups is already on display: the US homebuilder industry, for example, has come out vehemently against some of the proposed changes being floated by policymakers. Time will tell how successful any new legislation will be at productively broadening the base (i.e. reducing the loopholes and exclusions).

So what’s the takeaway? There are many miles to go before the proposal coming out today arrives at any kind of legislative certainty. As managers of portfolios invested for long term financial objectives, our views on taxes focus largely on how they impact, or do not impact, key economic drivers over the long term. We will continue to share with you our views as this process continues.