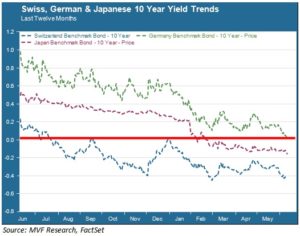

Today’s WMF is brought to you by the number 10. It’s the tenth day of the month, and it’s a day when 10-year debt is front and center on the capital markets stage. Switzerland and Japan have already crossed over into 10-year NIRP Wonderland, offering investors the curious opportunity to lock in losses for a whole decade. Now Germany is flirting at the event horizon; the yield on the 10-year Bund is just one basis point on the positive side of the line. One year ago all three benchmark yields were above zero, and Germany’s comfortably so. The chart below shows that the zero boundary, once breached, has proven difficult to cross back into normal territory.

Inventory Problems

Why do yields continue to plumb the depths? This comes down, as always, to a supply and demand question. In Europe, in particular, a big part of the problem lies on the supply side. The ECB is the big player (or, less charitably, the Greater Fool), but there are limits on its bond buying activities. Specifically, the ECB cannot purchase bond issues when their yields fall below the ECB’s own deposit rate, which is currently set at negative 40 basis points. That requirement cuts the ECB off from an increasingly large chunk of Eurozone debt; consider that the yield on German five year Bunds is now minus 0.43%. So further out the curve the ECB goes, and down come the yields.

Additionally, the ECB can purchase a maximum of one third of any individual bond issue, so it is constrained by the supply of new debt coming onto the market. Some observers estimate that the inventory of German debt for which the ECB is eligible to purchase will run out in a matter of months. If the ECB wants to continue monthly QE purchases according to its current program it will then have to consider (and persuade ornery German policymakers to agree to) changes to the current rules.

Meet the New Risks, Same as the Old Risks

Of course, technical issues of bond inventories and ECB regulations are not the only factors at play. The risk sentiment dial appears to be pointing somewhat back towards the risk-off end, if not for any particularly new set of reasons. Brexit polls continue to occupy the attention of the financial chattering class, with the vote looming in 13 days and a close result expected. Investors seem to be digesting last week’s US jobs report from a glass half-empty standpoint – slower payroll gains bad for growth, while improving wages mean higher labor costs which are bad for corporate earnings. Japan delivered up some negative headline numbers this week including an 11 percent fall in core machinery orders. Again, none of this is new (and for what it is worth, we continue to think it more likely that we will wake up on June 24 to find Britain still in the EU). But animal spirits appear to be laying low for the moment.

The Stock-Bond Tango

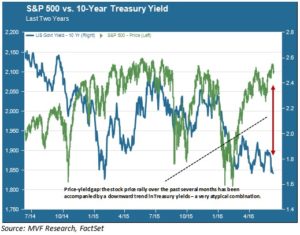

The recent risk-off pullback in overseas equity markets, though, is having less impact here at home. Yes, the S&P 500 is off today – but earlier in the week the benchmark index topped its previous year-to-date high and remains just a couple rally days away from last year’s all-time high. The really curious thing about this rally though – and why it is very much relevant to what is going on in global bond markets – is that recently stock prices and bond prices have moved largely in tandem. This weird tango has resulted in 10-year Treasury yields at a four-year low while stocks graze record highs. As the chart below shows, this is a highly unusual correlation.

This chart serves as a useful reminder that just because something hasn’t happened before doesn’t mean that it can’t happen. In fact, what is going on in US stocks and bonds is arguably not all that difficult to understand. Investors are in risk-off mode but are being pushed out of core Eurozone debt in a desperate search for any yield at all. US Treasury debt looks attractive compared to anything stuck on the other side of that NIRP event horizon. And that demand is largely impervious to expectations about what the Fed will or will not do. Short term Treasuries will bounce around more on Fed rumors, but the jitters will be less pronounced farther down the curve.

And stocks? There is plenty of commentary that sees a significant retreat as right around the corner. Perhaps that is true, perhaps not. Pullbacks of five or 10 percent are not uncommon and can appear out of nowhere like sandstorms in the desert. But – as we have said many times over in recent weeks – we do not see a compelling case to make for a sustained retreat into bear country. The economy does not appear headed for recession, money has to go somewhere, and negative interest rates have the continuing potential to turn bond buyers into stock buyers. If a pullback does happen over the summer, we are inclined to see it more as a buying opportunity than anything else.