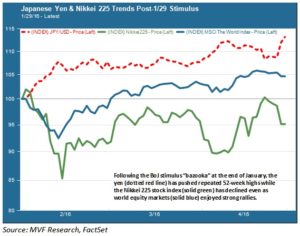

The language with which the financial press documents the doings of central banks has taken a notable turn towards military vernacular in recent years. We have “shock and awe” campaigns to talk up growth prospects, and jaw-clenched proclamations of doing “whatever it takes” to stave off collapses in currency, bond or equity markets. Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more! Descriptions of their policy implementation vehicles are likewise bellicose. Consider the “bazooka” by which Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda fired a new package of stimulus via quantitative easing and negative interest rates back at the end of January. Like most such stimulus programs, the explicit goal was to provide a monetary boost to stimulate economic activity, while the largely unspoken but implicit aim was to weaken the currency (the Japanese yen) and stimulate domestic asset prices. How’s that working out for the BoJ so far? Not so well, as the chart below shows. Since the 1/29 stimulus, the yen has soared against the dollar and the Nikkei 225 stock index has fallen even while world equity markets have enjoyed a broad-based rally.

Hold Your Fire

“Damned if we do, damned if we don’t” must be the frustrated sentiment in Nihonbashi, the Tokyo district where both the BoJ and the Tokyo Stock Exchange are located. Following another policy meeting this week, the central bank announced on Thursday that it would be holding off for the moment on any new stimulus measures. The no-action decision took markets by surprise, as most observers predicted the bank would serve up another cocktail of negative rates and/or increased asset purchases. Once again the yen jumped – this time by four percent in a single day – and stocks cratered.

The official reason for the decision to hold fire, according to Governor Kuroda, was that the bank is still assessing the impact of the January move. It would not be prudent, according to this argument, to implement new policies until members have a better sense of how the current ones are working. He added that the policy impact should be better understood in the not too distant future, giving a guideline of six months or so from implementation as a reasonable time frame. That sets up the possibility for another stimulus move in June, which of course would pull it firmly into the gravitational tractor beam of Janet Yellen and her FOMC colleagues. The Fed meets on June 14-15, and pundits are currently split as to whether rates are likely to rise or remain on hold following that meeting. Should the Fed raise rates in June, Kuroda’s thinking may go, it could give some added force to another round of BoJ stimulus for the Japanese economy. And such a move would be very much in keeping with the Japanese governor’s established penchant for big, dramatic moves rather than incremental policy tweaks.

Running Out of Ammunition?

Such a move would also support an increasingly prevalent view that while the BoJ’s bazooka may be in fine shape, it is running low on ammunition. The decision to move into negative rate territory was controversial when it was announced and continues to be a matter of contention in Japanese financial circles. There are limits to how far into negative territory rates can go, even if no one really knows where that lower bound is. On the quantitative easing side, any moves by the BoJ into riskier asset territory like common stocks are also likely to generate resistance.

Meanwhile, the economy shows few signs of improvement. At this week’s post-meeting press conference the BoJ announced a series of downward revisions to its economic forecasts. Growth is now projected to be 1.2 percent versus the prior estimate of 1.5 percent through March 2017. Inflation – which Governor Kuroda has pledged to see reach the target rate of 2 percent before he leaves office in 2018 – was also revised down from 0.8 percent to 0.5 percent. The likelihood of a return to 2 percent within the next 24 months is looking ever less likely. Labor market conditions have improved but, as in other countries, a fast clip of jobs creation is failing to deliver the kind of wage increases normally seen in the past.

Given this context, it perhaps makes sense that the BoJ would keep its limited store of powder dry for now and hope to get more bang for the buck (ahem, yen) in a June move. But it is a risky gambit; the Fed is far from certain to raise rates then, and any number of other unknowns could manifest between now and then to complicate the policy landscape. Governor Kuroda has two years left in his term to shore up the BoJ’s credibility. Increasingly, that credibility appears to be dependent on events beyond his control.