You might recall that we published a piece during the week before Thanksgiving called “The Case for Optimism,” focusing on some seemingly compelling reasons why the year ahead might be a very good one indeed for risk assets. Since then we have started to see the usual flow of year-ahead outlooks from our industry peers, and quite a few of them radiate a healthy level of optimism based on the same potential trends covered in our recent commentary. Investors know that it will be grim start to the year but – apologies to Shakespeare for a bit of paraphrasing – “now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this sun of Covid vaccines.” The expected rebound in business and household activity following the scaled-up distribution of the vaccines will, in the optimistic case, justify higher valuations, particularly as the Fed will keep interest rates near zero even as the economy kickstarts back into growth.

None of which is to say that there is no room for caution, however, and caution will be the theme of this week’s discussion. Amid the preponderance of rosy outlooks we see several cautionary admonitions.

Stretched Valuations

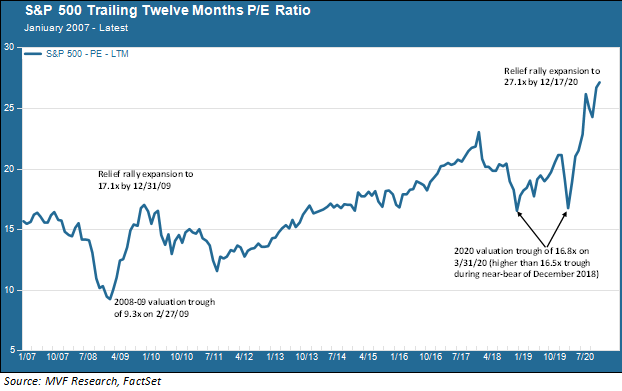

If 2021 really is going to see a stampeding of the bears, it is useful to ask from what starting point the rally would take place. In the chart below we show the current trailing twelve months price to earnings (P/E) ratio for the S&P 500 going back to 2007; this allows us to compare the current environment with that of the previous bear market in 2008-09.

In this chart you see that the P/E ratio fell to a low of 9.3 times at the nadir of the 2008-09 market, then experienced a customary “relief rally” from March to December 2009, topping out at just over 17 times, or a near-doubling from the low.

You can also see that the valuation trough in March 2020, at the peak of the market panic over Covid, was 16.8 times. The 2020 trough, in other words, was only slightly below the relief rally peak following the 2008 crisis. The P/E ratio fell further, in fact, during the near-bear market of October – December 2018 than it did during the coronavirus-related downturn.

Moreover we have seen the same kind of relief rally effect after this most recent downturn that we saw in 2009. At 27.1 times, the current P/E ratio is not quite double its March low, but another spurt of optimism from traders in the coming weeks would likely push the meter into the low 30s.

All of this is to say that we are not starting from a very low baseline. If stock are indeed going to go up in 2021 (which we would be inclined to say is more likely than a conspicuous decline), one has to wonder just how much upside there is given where valuations are today.

Interest Rate Constraints

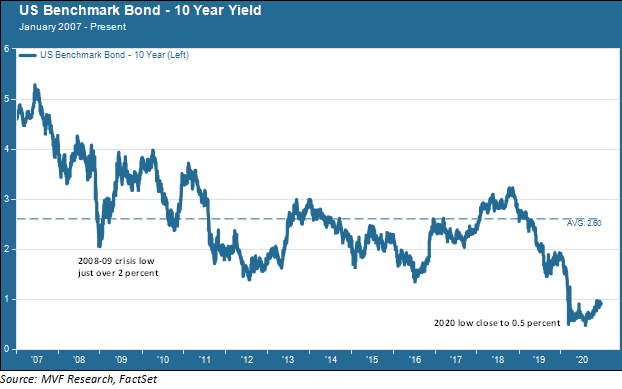

Now, an astute financial analyst might look at that P/E chart above and note the following: at no time during the 2008 crisis did the 10-year Treasury yield fall below two percent. The chart below illustrates the 10-year yield movement over this time period.

By contrast, fixed income yields today are much lower, with the 10-year having fallen as low as 0.5 percent this year and short-term rates being pegged to zero. This, the analyst would argue, justifies higher stock valuations because it makes the future cash flows of companies more attractive in present value terms. Analysts derive equity values by discounting forecasted future earnings back to the present at a discount rate; the lower the rate, the higher the present value of those future earnings. So we should expect valuations to be elevated from earlier market cycles as long as rates stay low.

That much is true; we would not argue with the sharp-minded analyst on that point. But the current low level of interest rates also presents a constraint that in turn poses a warning flag of sorts to the optimists. With the Fed funds rate at zero the Fed does not have the ability to use its traditional monetary policy tool any further without allowing rates to go negative – a policy the Fed has actively resisted so far and is reluctant to contemplate for future use. That does not mean the Fed does not have other tools – it showed us quite capably during the pandemic that it has a range of ways to keep markets calm when need be. Nonetheless, the absence of leeway on interest rates does constrain at least to some extent the Fed’s ability to respond to forthcoming crises. Given the extent to which investors have come to rely on the Fed to always be there with a bail-out option, this is not a small risk.

The Known Unknowns, the Unknown Unknowns and a Thought Experiment

Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld may be remembered for many reasons, but his catechism of the “unknowns” will surely endure. This week we have been given a taste of what Mr. Rumsfeld would probably have labeled a “known unknown”: cybersecurity breaches by foreign government agents. We learned over the course of the week that agents associated with the Russian SVR agency conducted a sweeping hack of a great many US government agencies and an even greater number of technology companies that support them. We know that cybercrime is one of the big threats always looming over the global economy; what is unknown is when the threat actualizes, how much damage is already done, whether this is ultimately not much more than routine espionage or whether our systems are indeed vulnerable to a targeted cyberterrorist attack. Such an attack, were one to occur in 2021, would probably upend all that’s been written so far in these year-ahead outlooks (including, of course, our own).

Think back to one year ago: December 2019. Lots of ink was spilled in forecasting what would happen in the world and its capital markets in 2020. Just about all of those outlooks (again, ours included) were rendered obsolete just one month into the new year with the emergence of a strange new virus in Wuhan, China that quickly became a global pandemic.

Now do this thought experiment: in December 2019 you actually have an accurate crystal ball that reads the following message to you: “The biggest story in 2020 is that a disease will originate in Wuhan, China and then spread to the entire world. In the US over 300,000 people will die as a result of the pandemic and our ability to rise up as a unified, strong country and take proactive measures against the virus will be shown to have largely fallen short.”

Armed with just that information, would you have predicted that China’s Shanghai Composite stock index would end the year up more than 30 percent, with the US S&P 500 up in the mid-high teens and the Nasdaq flying high over 40 percent for the year? And yet, that is exactly how this year went.

In our way of thinking it pays to do the hard work of analysis, it is important to develop an investment thesis and it is crucial to the long-term success of the money entrusted to us to stay disciplined. A healthy dose of humility – particularly in regard to the many “unknowns” that are always present but out of sight – is absolutely critical if we are going to do our job well and live up to the trust placed in us.