Imagine if someone had come back from the future to tell you, at the end of 2019, that the dominant news story of the year 2020 was going to be a virulent pandemic that arose in a food market in Wuhan, China. Would your first instinct have been to place a big bet on Chinese equities as a likely outperformer for the year? Probably not!

Winning the Pandemic

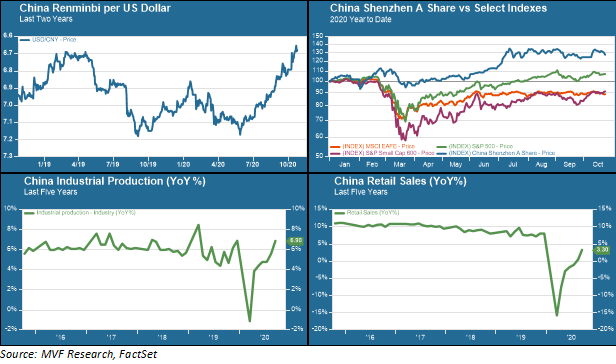

Yet the Shenzhen A-share index, a benchmark for Chinese shares, is up by nearly 28 percent as the year heads into its final two months. The S&P 500 – which has also enjoyed a rather better-than-expected rebound from the pandemic – is up by just seven percent. And a host of other risk asset classes from small caps to developed non-US equities (as well as most emerging markets not named China) remain stubbornly in negative territory, having been unable to recapture the hit from the depths of March.

Nor is the story just about competing stock markets. China’s economy is on track to be the only major global economy to sustain positive real GDP growth for the full year. Industrial production and retail sales, two driving forces behind GDP growth, are not far from their pre-crisis trend levels. All this has had an effect on the renminbi, the Chinese currency, which has seen an accelerated pace of growth in recent months. Not to mention the fact that, following the draconian shutdown of Wuhan back in winter, China’s success in managing the pandemic has far outshone that of the US and Europe.

The chart below provides a snapshot of these current developments.

The Promise and the Peril

China has beguiled Western investors, business leaders and entrepreneurs alike ever since Deng Xiaoping first proclaimed that “to get rich is glorious” in the immediate aftermath of the ruinous final years of Mao Zedong’s regime. But the allure has always been spiked with the perils of the unknown, in particular the opaque nature of the highly centralized decision-making structures that form and implement economic policy from Beijing. The Chinese system – a rigidly dirigiste form of managed capitalism with the florid rhetorical trappings of old Communist Party dogma – is quite unlike that of any other major economy.

Passive foreign investors in Chinese equities may not have had to deal with the red tape and rabbit holes that have tripped up many a globetrotting CEO, but the ride has been anything but steady. Even with the relatively impressive performance versus other equity markets this year, China’s Shenzhen index is still below its peak at the height of a frenzied bull market in the middle of 2015. This kind of volatility has kept exposure to Chinese risk assets at relatively contained levels for most Western-domiciled asset management models (although broad-based emerging market equity benchmarks like the MSCI Emerging Market index contain a disproportionate weighting of China-based holdings).

China In a Post-Pandemic World

The question worth thinking deeply about going forward is what China’s role in the world is going to be on the other side of the pandemic. Things are changing on several fronts to suggest that role may be more prominent than it has been. First of all, Beijing has been taking very deliberative steps to integrate its domestic market more closely with the global economy. The renminbi, the national currency, has never been freely accessible around the world in a way that would enable it to make a viable challenge to the US dollar for reserve currency status. That may be changing, however. In a similar vein, China’s domestic fixed income markets are opening up as well, and capital movements in and out of the county are being subject to fewer and less odious regulations.

The domestic consumer base is also changing. It is worth noting that nearly half of the entire volume of global initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2020 will be related to Chinese companies. This includes the upcoming listing of Ant Financial, a Chinese financial technology firm whose $30 billion offering will displace Saudi Aramco as the largest ever. Investors who continue to think of China’s economy as largely consisting of copycat manufacturers of cheap, frilly consumer goods are about 15 years behind the times; the country’s domestic consumer payments infrastructure, for instance, is arguably the most advanced in the world. China is also a leader in green technologies including the dominant player in solar energy.

The pandemic has shone an unforgiving light on the political, social and economic infrastructure of much of the world, most definitely including the so-called developed world. There was a time when the default assumption of policymakers in Brussels, London and Washington was that China’s opening up of its economy would eventually lead it to Western-style liberalism and democratic norms. That hope has largely faded. The bigger challenge ahead may well be for the democracies themselves to resist a model of economic success built on decisively anti-democratic foundations.