Stop us if you’ve heard this one before. As the end of the year approaches, investor attention suddenly focuses, laser-like, on China’s financial system. Share markets stumble on the Chinese mainland and in Hong Kong, leading to excited chatter about whether the negativity will spill over from the world’s second-largest economy into the global markets and throw a spanner into what was shaping up to be a most delightful and stress-free (at least from the standpoint of one’s investment portfolio) holiday season.

It happened at the end of 2015, with the S&P 500 falling apart on the last two trading days of the year and continuing the swoon through the first weeks of the new year. The majority of broad-market benchmark indexes lost more than 10 percent – the commonly accepted threshold for a technical correction – before sentiment recovered and bargain-hunters swooped in to take advantage of suddenly-cheap valuations.

Minsky Says What?

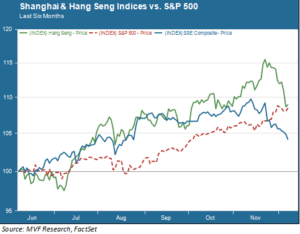

Share prices on the Shanghai stock exchange have fallen about 6 percent since reaching their high mark for the year on November 22. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index, with a proportionately large exposure to mainland companies, is down by about the same amount. The chart below shows the performance of the SSE and the Hang Seng, relative to the S&P 500, over the past six months.

Financial media pundits were quick to remind their readers of the “China syndrome” that played out, not only during that nasty month of January 2016 but also five months earlier, in August 2015 when Chinese monetary authorities surprised the world with a snap devaluation of the yuan, the domestic currency. It started to seep into the market’s collective consciousness that the phrase “Minsky moment” had been uttered recently in connection with China, drawing parallels to the precariously leveraged financial systems that fell apart during the carnage of 2008 (the late economist Hyman Minsky was known for his observation that prolonged periods of above-average returns in risk asset markets breed complacency, irresponsible behavior and, sooner or later, a nasty and sharp reversal of fortune).

Context is Everything

At least so far, fears of a reprisal of those earlier China-led flights from risk appear to be less than convincing. As the above chart shows, the S&P 500 has blithely plowed ahead with its winning ways despite the pullbacks in Asia. Now, US stocks have shown themselves time and again this year to be resoundingly uninterested in anything except the perpetual narrative of global growth, decent corporate earnings and the prospects for a shareholder grab-bag of goodies courtesy of the US tax code. But ignoring fears of another China blow-up is, it would seem to us, more rational than it is complacent.

For starters, consider the source of that “Minsky moment for China” quote; it came from none other than the head of the central bank of…China. Zhou Xiaochuan, the head of the People’s Bank of China, made these remarks during the recent 19th Communist Party Congress marking the start of President Xi Jinping’s second five year term. The spirit of Zhou’s observation was that runaway debt creation imperils the economy’s long-term health, and that is as true for China as it is for any country. In particular, Zhou appeared to be alluding to what many deem to be dangerously high levels of new corporate debt issuers (and speculative investors chasing those higher yields).

Working for the Clampdown

That message was very much in line with one of the overall economic planks of the 19th Congress; namely, that regulatory reform in the financial sector is of greater importance in the coming years than the “growth at any cost” mentality that has characterized much of China’s recent economic history. Following the Congress, the PBOC implemented a new set of regulations to curb access to corporate debt. These regulations sharply restrict access to one of the popular market gimmicks whereby banks buy up high-yielding corporate debt and then on-lend the funds to clients through off-balance sheet “shadow banks.”

These and similar regulations are prudent, but the immediate practical effect was to sharply reduce the supply of available debt and thus send yields soaring. The spike in debt yields, in turn, was widely cited as the main catalyst for the equity sell-offs in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

If that is true, then investors in other markets are likely correct to pay little attention. China does have a debt problem, and if the authorities are serious about “quality growth” – meaning less debt-fueled bridge-to-nowhere infrastructure projects and more domestic consumption – then the risks of a near-term China blow-up should decrease, not increase. Stock markets around the world may pullback for any number of reasons, and sooner or later they most probably will – but a three-peat of the China syndrome should not be high on the list of probable driving forces.