Last week was a very tumultuous one in the world of US politics, but it was fairly benign for US stocks. Or so it seemed. We got a number of calls from folks wondering why markets were not reacting more to the drama in Washington. Here’s the short answer: the market was in fact pricing a political story – just not the one that was unfolding at the Capitol on Wednesday afternoon. Always remember that the market is a cold-blooded and amoral beast. If it can’t put a price tag on something it largely ignores it, however much that thing may be jarring for humans with our emotional human sensibilities.

The Blue Wave’s Delayed Arrival

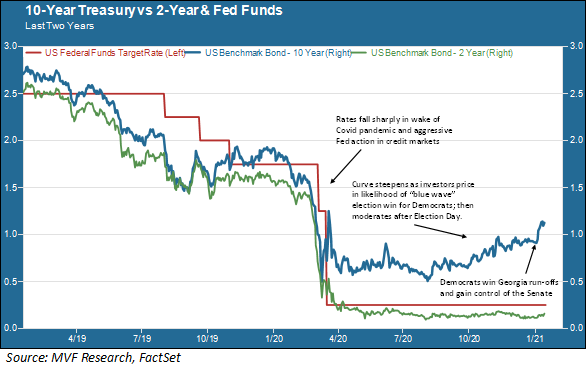

The political news that the market was paying attention to last week was the victory by the two Democratic candidates in the Georgia senate run-off, John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock. The impact of that news can be seen in one metric in particular: a resumed steepening in the 10-year Treasury yield curve. The chart below shows a two year comparison of the 10-year yield, the 2-year yield and the Fed funds rate.

The Georgia victory ensured that the Democrats will control the House, Senate and White House following the inauguration of President-elect Biden on January 20. For markets, this meant dusting off the “reflation trade” that had been put on hold after Election Day when predictions of a massive “blue wave” failed to materialize. The wave that finally arrived may be more of a gentle swell than a full-blown Waimea Bay giant, given that the Democrats’ margin in the House is smaller than it was before the election and the Senate hangs in the balance of a 50-50 split with Kamala Harris holding the tiebreaking vote in her role as presiding officer of the Senate. Nonetheless, it is enough to firm up the narrative of a torrent of new spending, pushing inflation – and therefore intermediate and long-term bond yields – higher. Indeed just yesterday the president-elect unveiled the first of two major policy initiatives, calling for $1.9 trillion in new spending on pandemic-related economic support and vaccine acceleration measures. A second announcement will follow next month and is expected to focus on infrastructure and healthcare.

But Will It Come to Pass?

The reflation trade is worth paying attention to for several reasons – it could extend the rotation out of growth stocks into value, small cap and other relative underperformers in recent years. And, of course, the curve steepening puts downward pressure on intermediate and long-term bond prices. But mostly it is worth paying attention to because a structural upward movement in inflationary expectations has the potential to cause some lasting damage to asset valuations. That said, it is far from certain that reflation is going to play out the way some of these pre-emptive moves in yields suggest.

Consider that $1.9 trillion relief package announced yesterday, for one. You can think of that as an opening gambit more than as a piece of legislation to hang your hat on. There will be plenty of opposition from Republicans in the Senate, where it still would need a filibuster-proof majority to pass via the conventional legislating process. The proposal contains relief aid for states and municipalities which was one of the two issues keeping relief from getting passed last year (the other was liability protection for businesses; both of these issues were ultimately dropped from the $900 billion relief package passed at the end of the year).

The reflation trade could die an early death at the hands of political gridlock. But even if the new administration adroitly works its will on Congress and gets some meaningful legislation passed, that does not by itself argue for a structural shift in inflationary expectations.

The key word there is “expectations.” Inflation becomes a problem when it factors into longer-term assumptions about prices by businesses and households. The last time this happened was in the 1970s, and there were plenty of good reasons for that – the US was running ever-larger budget deficits after the Vietnam war and social spending programs of the 1960s, OPEC sharply cut crude oil supplies and sent prices soaring, and the US dollar devalued sharply after the collapse of the Bretton Woods exchange rate mechanism in 1971.

We have a different situation today. A short-term inflationary jump can be expected later this year when the vaccine has scaled out to a majority of the population and demand soars for all the things that have been off limits for more than a year. But that jump would likely be temporary. Prior to the pandemic the economy was growing at a modest rate and consumer price inflation never sustained a rate above two percent. Even today the Fed’s Open Market Committee members don’t see inflation hitting a sustainable rate above two percent until late 2022 or even later.

As long as inflationary expectations are confined to a one-off post-pandemic event then the reflation trade, while it might persist for some time, is unlikely to imply much structural damage. But because the cost of a more extreme scenario is so high, it is wise to not lose sight of the fact that it could still happen.