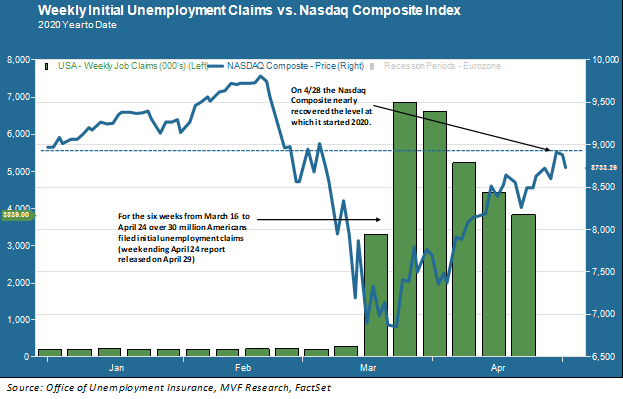

Let’s lead right off with the chart this week, because it visually encapsulates everything people have had a hard time processing in the past few weeks. On Thursday April 29 we learned that initial claims for unemployment filed in the previous week (from April 20-24) came in at 3.8 million, bringing the total number of claims filed in the past six weeks to an unheard-of record of over 30 million. The day before that data release, on April 28, the Nasdaq Composite stock index, a market benchmark heavily weighted towards technology-oriented companies, hit a post-pandemic high and closed just barely below the level at which it started 2020, back in the good old days when social distancing was just something you did with people you didn’t like. The chart is worth a thousand words.

When Bad News Is Good News (and Vice Versa)

By all empirical accounts the current state of the US economy is terrible, with millions out of work, businesses shut down and a creaky bureaucratic infrastructure trying to get record amounts of relief into the hands of those who need it most, with well-recorded difficulties. Almost nobody believes the near-term economic trajectory will look anything like the “V-shape” that some cheerleaders have been chirping about since the pandemic hit. So what’s with the V-shape in the stock market? While the Nasdaq pictured here has seen the swiftest approach back to pre-pandemic levels, other popular indexes including the S&P 500 and the much-loved-by-nightly-newscasters Dow Jones Industrial Average sport roughly the same shape.

While it may look ghoulish to see the fortunes of the stock market rising just as crippling unemployment is setting in, there is actually a pretty robust history for this “bad news is good news” dynamic. The stock market is essentially two things at the same time. First, it is simply a number meant to quantify all the expected future cash flows of the companies making up any given index. There should be a rational relationship between the present value of these expected future profits on any given day and the market price of the companies’ stock shares.

But then there is the second variable: shares of stock are actively traded between the hands of human agents who are anything but rational (and this is true whether the catalyst for any buy or sell order is a human voice yelling into a phone or an algorithm designed by a human brain responding to a preset trigger). Stock markets cycle between fear and greed. The fear catalyst was already at work before those terrible claims numbers came out. Once they did, though, fear turned to greed with a sense that a buying opportunity might be at hand. The novel thing about the market’s performance in March and April was not so much the “bad-is-good” dynamic as much as it was the speed at which one irrational emotion jumped over to the other irrational emotion with not much pause for thought in between.

Fundamentals and the Fed

In the long run the irrational spasms of fear and greed should give way to a more realistic picture of the economic environment and the ability of companies to earn money therein. But there is another important factor in the here and now, which is the Fed. Since the middle of March the US central bank has purchased more Treasuries and mortgage-backed bonds than it did throughout the three year span of the second and third quantitative easing programs in the middle of the last decade. It has expanded its net to include corporate and municipal bonds, which were not part of the response to the 2008 financial crisis. It even stands willing to buy junk bonds. And if these actions were not enough to stave off another sharp plunge in the market (a scenario still very much on the table) then many believe the central bank would not hesitate to jump in and buy stocks outright – in fact Japan’s central bank already does this.

Here’s the important point. All of this direct intervention by the Fed into credit markets – i.e. the markets for government, municipal and corporate fixed income securities – has the effect of keeping interest rates down at their historic lows. In the absence of the Fed as a buyer of last resort the bond market would be a great deal more chaotic and rates would probably be much higher. From a practical standpoint, bonds that offer almost no income stream at all (zero percent means zero percent) are going to push at least some proportion of the market out into other assets where they could find at least some yield.

What assets, you ask? Why, common stocks. Again, this is not a new development. One of the main intentions for the QE programs of the last decade was exactly this – pushing investors out of their fixed income comfort zones into riskier stocks where at least they were assured of a dividend payout, and some additional capital appreciation if all went well. Low interest rates and a stable bond market encourage more risk-taking even among highly conservative investors like pension funds and insurance companies.

Don’t Sweat the Short Term

So how do you make reasonable predictions about what the market is going to do in the short run? Quick answer: you don’t. During a period of high uncertainty like the one we are in now the best assumption to make is that there will be lots of volatility – down, then up, then down and up again with no consistent timing. Meanwhile we continually absorb and process new information about the economy and – especially – about the most important issues related to the health crisis like the pipeline of possible vaccines and antiviral drugs, better access to testing and prudent standards for coming out of total lockdown. Over time these drips and drabs of data start to form a clearer picture.

You can’t stop the fear and greed – they always have been and always will be part of how the market works. But you can save yourself some sleepless nights by tuning out the noise and paying attention to those things that will matter in the long run.