It’s a strange economy, this one. All of the following happened this week: several data releases confirmed that manufacturing activity is hovering barely above the threshold for contraction; US consumers appear to be more confident about the economy than at any time in the last three decades apart from the very peak of the giddy late-1990s growth cycle; the Core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) indicator, the Fed’s favorite measure of inflation, registered an anemic 1.6 percent year-on-year expansion; and today’s jobs report showed basically more of the same with a healthy clip in payroll additions and wages growing at a brisker rate than inflation.

Oh, and the Fed cut its target Fed funds rate range by 0.25 percent, which came as a surprise to zero people but a disappointment to many for whom 25 basis points just doesn’t deliver the intravenous jolt they have come to need. And the trade war is back on, apparently, just one day after Fed Chair Powell noted an apparent recent subsiding in trade tensions. Conspiracy theorists, discuss amongst yourselves.

Insure This

That hotchpotch of mixed economic data points described above points to the likely thinking behind the Fed’s move this week. There is evidence of a slowing pace of growth (hence the manufacturing production data, which tend to serve as a leading indicator) even while consumers are as happy as pigs in mud and job creation keeps up its record-breaking pace. Corporate earnings season is winding down and a second straight quarter of EPS declines (albeit modest) is the likely outcome. Inflation seems permanently stuck in second gear. An insurance cut – which is how Powell characterized it at the post-FOMC press conference – would seem to make sense. At the very least, it is hard to see how it could do much harm in the absence of any plausible argument for an overheated economy.

The Longest, Least Productive Growth Cycle

Overheated, to be clear, is a word with entirely no relevance to what is by now the longest economic growth cycle on record. In previous growth cycles the Fed had to engineer interest rates back up above at least five percent to cool off late-cycle consumer binges and capacity build-outs. Previous cycles also had more of something this one has pretty much gone entirely without: organic, productivity-driven growth.

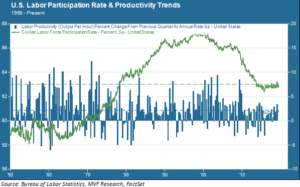

The chart below illustrates the US productivity trend since the earliest postwar economic cycles, along with the labor force participation rate. These two indicators tend to be largely ignored in the quarter-to-quarter analysis that dominates mainstream economic reporting, but they are central to the long term growth equation. As the chart shows, they have both been subdued throughout this entire growth cycle.

This chart illustrates the dilemma that economic policymakers face in trying to anticipate what happens after the effects of short term monetary and/or fiscal stimulus wear off. This economy has survived on eleven years of aggressive monetary stimulus and intermittent doses of fiscal largesse. The effects of the most recent fiscal injection – the tax cuts that went into effect in 2018 – are pretty much over. Corporations bought back massive amounts of their own stock and some even increased their capital spending on productive assets, but by this year’s second quarter private sector nonresidential investment had already waned as a contributor to gross national product.

Demographic Doldrums

Demographics also work against the economy. The labor force participation rate is likely to stay stagnant as the population skews older and towards retirement. The segment of the population below age 18 is in decline. Overall population growth, at 0.62 percent according to the Census Bureau’s most recent reading, is the lowest growth rate since the Depression-scarred environment of 1937. None of this is going to help growth. That leaves productivity, of which there has not been much. The productivity report for the second quarter comes out on August 15, and is expected to reflect another below-trend reading.

In the meantime, though, a slowing economy does not necessarily mean one in near-term danger of falling into recession. Perhaps the silver lining in the anemic growth formulation is less volatility on the downside. Lower growth, lower risk – just like a boring, stable utility versus a high growth start-up tech company, perhaps. Maybe that will work out in the long run – but in the short run it is unlikely to be either helped much or hurt much by however many “insurance” cuts the Fed has planned.