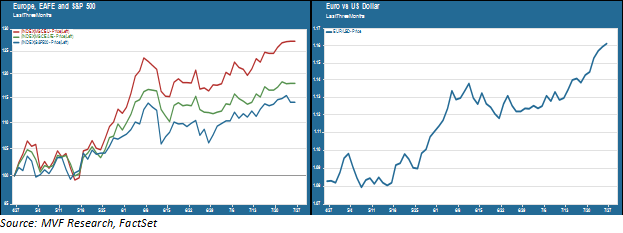

Something unusual has been happening in recent weeks. Equity markets outside the US, those long-suffering European and Asian bourses trailing in the flamboyant wake of the seemingly indestructible S&P 500, have woken up and gotten their game on. In the chart below you can see on the left-hand panel that the MSCI EU index (the crimson trend line), comprising equities in the European Union, has resoundingly outperformed our domestic blue-chip index over the past three months. So, to a lesser extent, has the MSCI EAFE index (in green) which includes developed Asia-Pacific markets along with Europe.

An FX Tailwind

What’s behind this surprising spurt of outperformance? The right-hand side of the panel explains the lion’s share of the answer. In the past three months the euro – the currency in which most EU equities are denominated – has risen by 7.4 percent against the US dollar. Think of it this way: if you are a US investor and you own assets denominated in euros, the value of your assets goes up (in US dollar terms) when the foreign currency appreciates. You add the currency gain to whatever amount your asset grew in its own home-currency terms, and voila – enhanced total return.

Dollar weakness versus the euro, in other words, is the dominant variable explaining the performance of EU stocks versus their US counterparts. Now, this in itself is not particularly newsworthy – currencies go up and down against each other all the time. But something happened in the EU this week that has the potential to give a more structural (as opposed to merely cyclical) boost to the European currency and to European assets more generally.

The M&M Effect

The EU is famous for being unable to reach common agreement for important region-wide initiatives. Historically a not insignificant part of the difficulty has been the intransigence of Germany, the EU’s largest economy, in lending fiscal support to the region’s weaker and more indebted members. But several weeks ago German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron came together in support of an aggressive €750 billion relief program (about $870 billion) to help EU nations provide relief to their citizens and businesses as the coronavirus pandemic continues to weigh on the economy. Merkel and Macron (who would be called “M&M” more often if they actually cooperated more often) spearheaded a long and often contentious series of negotiations to bring the rest of the EU on board. They finally achieved success at 5:31 am this past Tuesday morning, Brussels time.

Now, €750 billion may not sound like much in a world where central banks routinely speak of printing trillions of dollars for economic support. What makes the EU program noteworthy – what justifies the “potential game-changer” language in our headline – is how the program will be funded. The EU will issue regional sovereign bonds, likely to come with a triple-A rating by the credit rating agencies. This exceeds by a magnitude of 13 times or so the amount of EU sovereign debt currently in existence (a small amount of issuance mainly used to fund loans to Ireland and Portugal during the Eurozone crisis a decade ago). It represents a new safe haven asset class that will likely find its way into many asset allocation decisions, the most important of which is likely to be central bank foreign exchange reserves.

A Paler Shade of Green

The overwhelming majority of foreign exchange reserves held by national central banks are, unsurprisingly, denominated in US dollars. The greenback has been the world’s reserve currency since the end of the Second World War. But the world today looks nothing like the world of the Bretton Woods framework that oversaw the first quarter-century of the postwar period. China, which barely had an economy to speak of at the time, is now the second largest economy in the world. It is also the largest single foreign holder of US dollar assets, mostly Treasury securities. And, in a very much related development, it is engaged in an increasingly hostile contest for global influence with the US.

Now, nobody rationally expects that China is going to start dumping Treasury bonds wholesale – that would be an impulsive and self-defeating move contrary to the long game played by Xi Jinping and his Beijing mandarins. But the ability to diversify its reserve mix to a greater supply of euro-denominated paper will probably be of great interest to Chinese central bankers. It could be an important thread in a gradual weakening of the dollar’s singular preeminence in world markets.

None of this will happen overnight, if at all. Tectonic shifts are usually not the result of one single event but rather of thousands of independent, seemingly unrelated tensions that build up and eventually bring the plates into collision. It’s worth one’s time to pay close attention to trends in euro-denominated assets in the coming weeks and months. They may be suggestive of more structural changes to follow.