Any mention of the European Union in recent days is likely to elicit a bemused shake of the head at the inexplicable ineptness of the entire British government as it dithers over how to dig itself out of the hole its leaders dug for themselves three years ago in deciding to have a referendum on Brexit (we will take this opportunity to reaffirm the prediction we made back in the fall of last year: Brexit will get delayed, then delayed again, and eventually will get put to a referendum and not happen, which is also apparently what investors in the British pound sterling think). But while the world looks on at the impasse between the Continent and those on the other side of the Channel, there is something of potentially larger significance for the EU in the long term. That something is bubbling up in Italy.

On March 22 the Italian government intends to sign a memorandum of understanding with China to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative under the auspices of a package of loans from the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (AIIB). The signing will take place in conjunction with the visit to Rome by Chinese president Xi Jinping, and it brings a whole slew of testy geopolitical issues right into the heart of the single currency union. Italy is technically in recession, with what is now the second-highest unemployment rate in Europe, and increasingly receptive to China’s attempts to insinuate itself into the nation’s economic and political system.

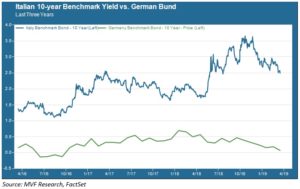

Uneasy Calm

On the surface of it, things don’t look all that dire from a financial markets perspective. Investors have been pouring into Italy in the opening weeks of 2019. The chart below shows the spread between benchmark Italian 10-year bonds and their German Bund equivalents, which has come down considerably after spiking at several junctures in 2018.

Italian paper now trades at yields around 100 basis points less than last year’s peak. That is hardly a sign of investor confidence in Rome, however, and more a manifestation of this economic cycle’s longstanding obsession: chasing yield. That obsession turned stronger still with last week’s pivot by the European Central Bank back to stimulus mode. As we noted in our commentary last week, the ECB’s about-face is not good news for a regional economy where growth and productivity have flatlined (productivity, which is the key driver of economic growth, contracted in the Eurozone in both the third and fourth quarter last year by the widest margin since 2009). Italy’s domestic woes, headlined by that poor job market and a fall in industrial production, are at the vanguard of the region’s economic ills.

Follow the Money

The practical significance of Italy’s newfound dalliance with China and the AIIB may not be readily apparent for some time yet. The variables that alter the course of complex systems like the global economy don’t always make themselves known in understandable ways. But the Belt and Road Initiative is arguably the largest and most progressive infrastructure project going on anywhere in the world now. The AIIB – and remember that this is a multilateral financial organization aiming to encroach on the longstanding domain of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – makes a point of playing by international rules rather than the more secretive practices of, say, the China Development Bank or the Export-Import Bank of China. Its attraction for struggling countries – including those in both western and eastern Europe – is undeniable.

As Europe continues to wrestle with growth and support its own sources of growth financing, it will become ever harder to resist China’s siren song. And that has profound implications for maintaining unity and cohesion within the EU – more profound, perhaps, than even the sorry farce of Brexit.