The old guessing game is back: who’s right? A couple things happened this week to bring this question front and center. On Wednesday, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the Fed’s monetary policy deliberators, released its economic projections for the near future while resolving to leave short-term interest rates at the current level of zero (technically, a band of zero to 0.25 percent for the Fed funds rate that banks use for overnight lending). The FOMC’s overwhelming consensus is that rates will stay at this level at least through the end of 2023.

Also this week, intermediate and long-term interest rates kept rising steadily, with the 10-year Treasury yield pushing through 1.7 percent. That’s not a particularly noteworthy level – the 10-year was trading over two percent as recently as summer 2019. But the pace of the increase has been of concern to market observers. Treasuries are supposed to be the ultimate safe haven investment, so when volatility rises to unusual levels, people notice. The sharp rise in bond yields strongly suggests that the market is not buying into what the Fed is saying about the economy, inflation, and its short-term rate policy. Who’s right?

Sugar High with a Touch of Inflation

The big number that got everyone’s attention at the FOMC press conference was the GDP projection for 2021. Just three months ago, at the December meeting, the median growth projection was 4.2 percent; on Wednesday we learned that the Fed now expects GDP to grow at 6.5 percent. That’s more than at any time since 1983. The chart below shows the ten-year trend for year-on-year GDP growth along with inflation, using the Fed’s go-to measure of core personal consumption expenditures (PCE). We indicate where the Fed expects each of these numbers – GDP and inflation – to be in 2021.

So the Fed expects core PCE to be 2.2 percent in 2021, also higher than its December projection of 1.8 percent. But as the chart shows, 2.2 percent is only slightly above the peak levels the index reached on a couple occasions in the low-inflation economic cycle of the 2010s. Why does the Fed think the much higher GDP growth rate won’t entail a more robust bout of inflation?

The answer articulated by Fed Chair Jay Powell during the press conference, and consistent with everything he has been saying for many weeks now, is that the 2021 growth will be more of a sugar high than it will be a sustainable trend. By 2023 the Fed thinks growth will have subsided back to the pre-pandemic trend of somewhere around two percent. The median FOMC projection for GDP growth in 2023 is 2.2 percent (actually down from a 2.4 percent projection in December) and the long-run assumption is just 1.8 percent. Those are not numbers likely to generate a bout of 1970s-style inflation. That, in turn, is why the Fed is so confident it can keep short-term rates so low, for so long.

The Bond Market is Vigilant, and Sometimes Wrong

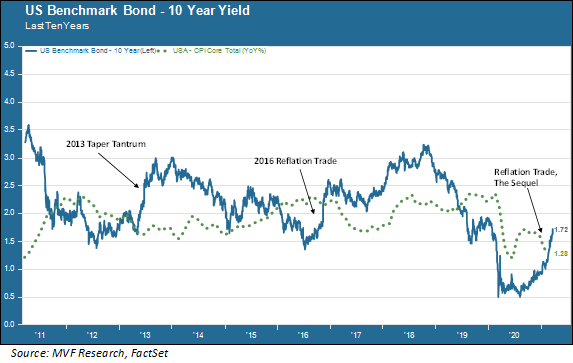

So-called bond market “vigilantes” have a long history of doubting the wisdom of Washington, such as it may be, on matters of financial rectitude. The sharp rise in yields that has characterized much of the current year to date is the most recent manifestation of this conviction that a flood of easy money will inevitably lead to soaring consumer prices. However, the bond vigilantes have been known to be wrong. In the chart below we show a couple instances in the past ten years when the market got ahead of its skis.

Back in 2013 there was a growing consensus in the bond market that economic growth, which was kicking into a higher level with a steady improvement in the labor market, was going to engender inflation and require the Fed to tighten the flow of money. All the bond vigilantes needed was a catalyst, and then-Fed chair Ben Bernanke supplied it with one word: taper. As the chart shows, a dramatic rise in rates followed this Delphic one-word musing. But inflation, measured here by the core consumer price index (CPI), didn’t go bananas, as we all now know. And the Fed kept its policies largely in place for the next two years.

The second instance of bond yields overshooting themselves happened in late 2016, starting the day after the presidential election. Because of a single mention of “infrastructure” in the victory speech that evening, a consensus formed overnight that a massive wave of public spending was about to be unleashed. That flood of money pouring into new roads and bridges and whatnot was sure to – all together now – unleash a major surge of inflation. Of course, the infrastructure programs never happened and the inflation never surged. But give the bond vigilantes credit – they are consistent no matter what.

So here we are at Reflation Trade – The Sequel (or Part Deux if that’s more to your taste). This time the bond vigilantes at least have some more data on their side, in the form of the trillions of dollars already deployed to fight the pandemic and bring the economy back to health. And yes – there is a possible infrastructure program in the works and there is even a somewhat reasonable chance that something could actually pass. Plus, of course, the expected surge in demand we expect will come about in a newly-vaccinated world by the second half of this year.

So the vigilantes might get their day in the sun. But we also find very little to quibble with in Jay Powell’s more measured take on longer-term economic expectations. What happens in 2021 is most likely to be a highly unusual confluence of events, following the extremely unusual things that have transpired over the past twelve months. It’s way too early to make a final ruling on who’s right. But of all the old sayings in the financial industry that really have stood the test of time, “don’t fight the Fed” is probably still at the top of the list.