The Federal Open Market Committee meets again on July 29-30, and the consensus expectation is that the Committee will once again hold the target Fed funds rate at the current range of 4.0 – 4.25 percent. Unlike recent decisions, though, this one may not be unanimous. A small subset of the FOMC’s twelve voting members has been quite vocal in recent weeks about the desirability of a July rate cut. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this strain of Fedspeak has played out in the context of the increasingly strident rhetoric from the White House urging (inadvisably and inappropriately) for interest rates to be slashed. To appreciate why a pause is the right move for the moment, let’s consider a forty year history of FOMC interest rate decisions and the economic conditions in which those decisions were made.

Jobs and Prices

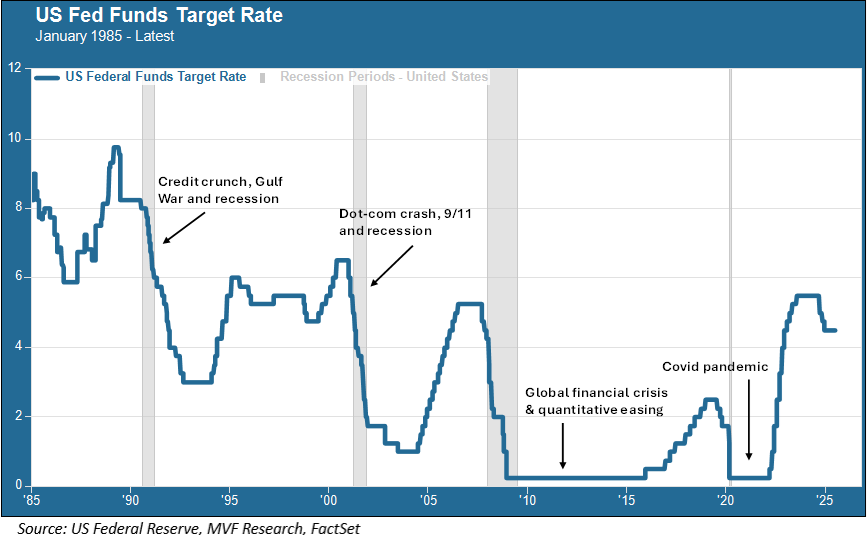

The Fed has two jobs, made explicit in its dual mandate: stable prices and full employment. When a hot economy threatens to unleash higher inflation, it’s time to raise interest rates and cool things off. Conversely, when the unemployment rate starts to trend sharply upwards, then a policy of rate cuts is appropriate as a way to stimulate the economy and generate job growth. Simple, right? Not really. The Fed is not in possession of a crystal ball any more than you or we are. The FOMC has to work with whatever data it has to figure out how dire the situation is and when the right time is to execute the decision. As the chart below shows, however, the Committee has done a pretty good job of this over the past forty years, with each of the four major rate cut cycles coinciding with an economic recession.

Those rate cut decisions, in 1990, 2000, 2007 and 2019 respectively, look even more prescient when considered in conjunction with the employment circumstances of the time. The unemployment rate rose to a maximum level of 7.7 percent, 6.1 percent, 9.9 percent and 14.8 percent over the course of those recessions. The Fed fulfilled its mandate by following policies aimed at bringing unemployment back down (which, in each case, it did).

When the Fed Stayed Put

And then there was the case when the Fed paused. This followed the rate hikes of 1994 (which caught financial markets by surprise), when the Fed took preemptive measures to head off what it feared could be a return of higher inflation. By April of 1995 the Fed funds rate was at 6.0 percent. There was a slight uptick in unemployment a couple months later and the Fed brought rates slightly lower, similar to what the Committee did last September in easing back from the maximum range this cycle of 5.25 – 5.5 percent.

And then – nothing, for two years. In the mid-1990s unemployment continued falling, and growth perked up without an undue amount of attendant inflation. Given the data at hand, the Fed didn’t need to act again until September 1998, when the Russian debt crisis and the ensuing collapse of the Long Term Credit Management hedge fund brought fears of a systemic financial market crash (those fears proved short-lived, and the Fed resumed raising rates in 1999).

And now back to the upcoming July 30 FOMC decision. The unemployment rate is currently 4.1 percent, and it has been close to this level for several months, along with a fairly stable level of gains in nonfarm payrolls. Meanwhile, the core Consumer Price Index rate is 2.9 percent, still meaningfully above the 2.0 percent target rate. In the CPI report that came out this past Tuesday, it was possible to see incipient indications of the tariff effect on certain categories of goods such as apparel and home furnishings. The full inflationary effect of tariffs remains an unknown variable.

In terms of that dual mandate of prices and jobs, then, the data available today continue to support a strategy of “better safe than sorry.” Hold for now, and see what the price and jobs data say as the calendar heads into the next FOMC meeting in September. And please, Fed members, stay away from the toxic politics of it all.