A few weeks ago we took note of the lack of breadth in the US stock market rally this year, with a small number of outsize tech companies (mostly with a good AI story to tell) driving the lion’s share of gains in the year to date. Since that time there has been a flurry of commentary among the financial chattering class about a possible rotation on the horizon. Is there anything to the chatter, or is the putative rotation out of mega-cap growth into…well, something else, just words with which to fill up the minutes on CNBC’s “halftime report” and its ilk?

Impressive, But Not Unprecedented

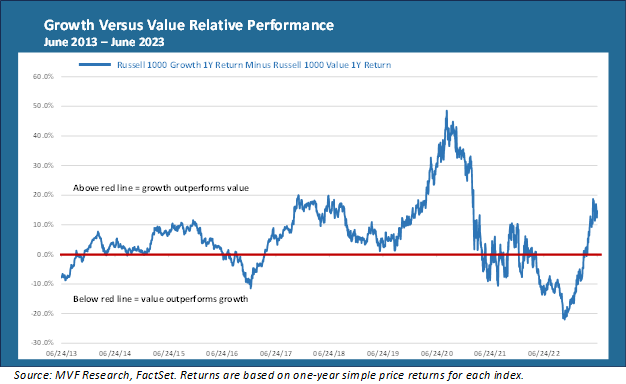

The performance of tech and other growth-related stocks has indeed been impressive this year. The Russell 1000 Growth index, as of the June 22 close, was up around 26.4 percent since January 1, while its counterpart the Russell 1000 Value index was up a paltry 1.7 percent. That’s a pretty big gap – no wonder those “rotation” chyrons were flying across the financial TV screens. But we’ve been here before. In fact, when we’re talking about growth outperforming value, we’ve been here quite often in recent years. In the chart below we show the relative performance of growth versus value for the past ten years.

Each data point in the above chart represents the difference between the one-year Russell 1000 Growth index return and the one-year Russell 1000 Value return. If the difference is positive, i.e. above the horizontal red line, it signifies growth outperforming value. Every data point below the red line indicates a period of outperformance by value over growth. As the chart makes clear, the last ten years have been dominated by growth stocks (most often, though not always, by the mega-cap leaders), and never more so than in the heady days of the pandemic. That all changed last year, of course, when the Fed began its monetary tightening program and growth stocks took a hit. Value stocks had their best run in the last decade during this period.

No Magic To Mean Reversion

Over time, either-or propositions like value versus growth will cycle back and forth. Some investors look at these charts, with their seemingly inevitable mean reversions, and figure there is a way to calculate these cycles and profit from timing them. We, however, do not subscribe to that school of thought. Mean reversion is not driven by anything other than thousands of market factors at play that generally only make sense in hindsight. Trying to interpret these factors in real time can lead to misguided convictions.

For example, there was a brief period of outperformance by value stocks in late 2016 that was driven largely by a whopping misconception on the part of investors that the forthcoming administration of Donald Trump was going to unleash a torrent of infrastructure spending that would “reflate” the economy and drive interest rates up. No such reflation (or infrastructure, for that matter) happened, and in due time the market figured that out. More recently, the market’s complacency about inflation and the Fed’s response to inflation caught quite a bit of the so-called smart money flat-footed in last year’s reversion to value stocks.

So is there another Great Rotation brewing? It’s certainly possible. As we have noted many times in the past several months, the market’s expectations for a near-term Fed pivot to cutting interest rates were out of step with what the Fed itself was actually saying – and that misreading of the FOMC’s tea leaves has arguably been one contributing factor to growth’s outperformance in 2023 (though the bigger story there, as we recently pointed out, is the market’s newfound obsession with everything AI). Now investors are bracing for not just one, but potentially two more rate hikes before the Fed decides to hold – and potentially hold for a long time if those sticky service-sector prices refuse to budge. That could give a further tailwind to value.

On the other hand, we are also seeing a renewed focus on the potential for a recession. The yield curve is once again flirting with its widest inversion since the peak of the Volcker era more than 40 years ago. Those concerns could be particularly hard on sectors like financials, energy and industrials that feature prominently in value indexes.

What we are seeing in the market today though, for what it’s worth, is more directionless than anything else. Playing things close to the center is perhaps the most advisable strategy for the time being.