In all fairness there is a lot of conflicting news out there today, enough to seemingly justify the whiplash-inducing lurches back and forth by major asset classes this week. Monday brought with it news of a coronavirus vaccine that had demonstrated 90 percent efficacy in trials pitting the drug, developed by pharmaceutical giant Pfizer in partnership with biotech developer BioNTech, against a placebo. Game changer! Yes, but…how long until it can come to market? What about the unprecedented number of new cases and hospitalizations that look set to get much worse well before a vaccine is at hand? Do we double down on the “back to normal” sectors of the economy, or stick with the winners of lockdown mode?

Or the election: Yes, we have a President-elect and Vice President-elect (and despite all the noise and misinformation and frivolous lawsuits, that result will stand the test of the 68 days between now and Inauguration Day). But the Senate is still up for grabs with the two run-off seats in Georgia scheduled for early January, the result of which could make all the difference to what does and does not get accomplished in Washington in 2021 (including fiscal spending, taxes, regulations and other things that matter to investment markets). Do we dust off that playbook for higher rates and inflation, or assume that gridlock (last week’s conventional wisdom) will rule indefinitely?

The Tremulous Ten-Year

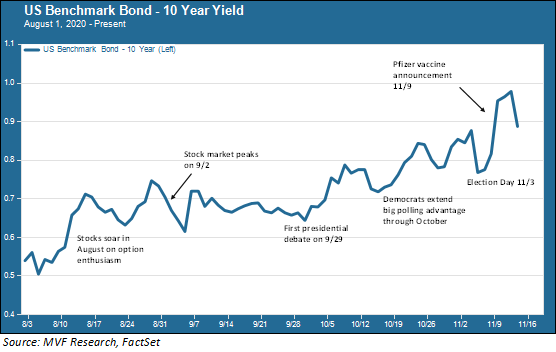

What about the Fed? The central bank sees stable credit markets as a necessity for facilitating the return of economic growth. Jay Powell and his colleagues will have found little to love about the gyrations in the intermediate-long term bond market in recent days. The chart below shows the pattern in the 10-year yield over the past three months.

The benchmark 10-year has been gyrating all over the place since Labor Day weekend. Coming out of a rip-roaring August in the stock market, safe haven bond yields were still mostly elevated from earlier levels when the S&P 500 peaked on September 2. But yields soared near the end of the month as the first presidential debate proved to be a polling disaster for the incumbent president and solidified expectations of a Democratic win. That trend kept going throughout much of October and surged into the final run-up to Election Day.

That day, as we discussed in last week’s commentary, threw cold water over the notion of a Democratic sweep of the table and a resulting massive double dose of pandemic relief and infrastructure spending. The 10-year yield plummeted in the immediate aftermath of the election. But then came Pfizer’s vaccine announcement and with it the potential for a return to growth in those sectors of the economy hardest hit by the pandemic. On the back of that news yields jumped once again, nearly hitting the one percent level that would be fully double the yield at its lowest points earlier in the year.

Or…maybe not. This week has been an unending count of grim statistics for the pandemic. Daily new cases are now setting records upwards of 150,000 (that’s about twice the highest levels in the prior wave in July). Hospitalization rates are also at records and straining health care systems just about everywhere in the country. However soon the vaccine is able to make it through the final regulatory steps, out of the lab and into retail health care centers for distribution, it will not be soon enough to mitigate the dire conditions of the present, the lives that will be lost and the ongoing suffering of the many who will experience the pernicious long-haul effects of the disease.

The Upside and the Downside

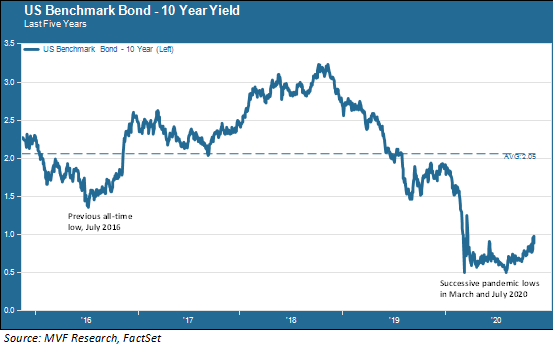

So where to now? This current indecision indicates the potential for wildly different scenarios. But stepping back to take a longer-term view of where rates are today suggests that there is more space on the upside (i.e. interest rate risk) than the downside. In the end it may come back to the Fed.

As the above chart shows, yields have come down considerably from where they have been for most of the past several years. If the 10-year were to double from where it is today, that movement would put it roughly in the middle – a bit below average even – of its trading range over the past five years. It’s not hard to envision a scenario where rates rise to that extent or even more. For example, a scenario of the vaccines moving full speed ahead towards distribution and a Democratic pickup in the Georgia Senate races (which would leave the Senate at 50/50 with Vice President Harris as the tiebreaking vote) would potentially bring about such an outcome.

Would the Fed intervene? Perhaps not. If the upside risk in yields is borne out by a recovering economy, receding health crisis and sufficient fiscal support then the Fed is less likely to extend its heavy hand as far out as 5 or 10 years on the yield curve. The central bank would be more likely to intervene directly if the fragility of the economy were to suggest it could not withstand a meaningful organic upward movement in rates.

All of these variables remain big “ifs” in the present moment, which we interpret as a signal that now is the time to keep one’s powder dry and to refrain from the kind of speculative bets that could go massively wrong. We will continue paying close attention to the bond market. An old saw on Wall Street has it that “where bonds go, stocks often follow.” Useful words to follow in these strange times.