The Efficient Market Hypothesis, one of the cornerstones of modern financial theory, argues that asset prices always reflect every single shred of information available to investors. Such information, aver EMH’s acolytes, is instantaneously processed by investors through a rational, omniscient, net present value-weighted assessment of probability-weighted future outcomes. Any mispricing between assets and their real underlying value is instantaneously arbitraged away; there are never any $20 bills lying on the street as a free lunch to passers-by.

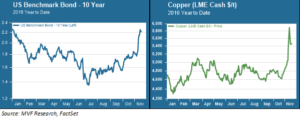

If the EMH worked as advertised, then the reaction to last week’s presidential election by fixed income yields and industrial metals would have been…well, in our view, not particularly interesting. Instead, the reaction was eye-catching indeed, as shown in the chart below, which forces the question. Do those spikes in copper prices and the 10-year Treasury yield reflect a hyper-rational pricing of all information available to thinking women and men? Or, rather, are they those proverbial $20 bills fluttering along the pavement?

Runnin’ Down a Dream

The meme that took hold almost as soon as Trump uttered the word “infrastructure” in his victory speech was “infrastructure-reflation trade.” Anyone watching the futures market saw this meme go viral as Tuesday morphed into Wednesday. The idea behind this whiplash in different asset classes appears to be: a torrent of federal spending cascading into US infrastructure projects, piling billions onto the federal deficit and igniting an inflationary heatwave. Bond yields would rise (inflation), and industrial metals prices would soar (demand). If this outcome were highly likely, then EMH would be doing its job just fine as assets instantaneously absorbed the news and repriced.

But a more truly rational assessment, in our opinion, would be that this infrastructure-reflation scenario is very, very unlikely to happen. Infrastructure has not been and will continue not to be a top priority for Congressional Republicans. Even if an infrastructure bill were to make its way through the legislative sausage factory, it would be in the end a very watered down version of anything Trump may have promised on the campaign trail. Even then, there would be a significant lag between the passage of any such bill and the formalization of “shovel-ready” projects to be on the receiving end of the funds. Even then, the net impact on headline macroeconomic data points like jobs or consumer prices would very likely be muted for the foreseeable future.

In short, we believe the “infrastructure-reflation trade” is little more than a mirage, a knee-jerk reaction more than a rational expression of future outcomes, and unlikely to be the kind of paradigm momentum shift in asset class trends many observers continue to believe is happening.

Tax Cuts Trump Public Works

The 2016 election does mean one-party rule, and this means an ability to push through economic policy in a way that the gridlocked Washington, DC could not achieve for most of the past eight years. But behind the smiling façade put up in public there are, by our reckoning, two distinct power factions in the Republican Congress with which the incoming administration will have to horse trade. There is Paul Ryan, the House Speaker who probably better than anyone else in Washington knows exactly what he wants to accomplish in the way of economic policy this year. These goals are simple and widely known: tax cuts for the wealthy, and far-reaching deregulation & de-funding with an emphasis on the financial, health care and energy sectors. “Ryanism” is in essence the core fiscal agenda that has motivated Republicans and their conservative donors & lobbyists since the Reagan era. We expect early policymaking to focus nearly exclusively on these issues.

The second power faction, then, are the legislators on Ryan’s right wing flank, the self-styled Freedom Caucus. This bloc would pose a further obstacle to any infrastructure bill that might come out of horse trading between Ryan’s team and the new White House. While the Freedom Caucus is arguably animated more by cultural issues than economic policy, they are strenuously opposed in principle to government spending outside of narrowly-defined defense obligations. The Freedom Caucus is where the “reflation” part of that infrastructure-reflation trade goes to die. Reflation would necessitate the large-scale creation of new, debt-financed money. The votes simply would not be there. The more hard-line caucus members are likely to push hard for dramatic spending cuts even to offset the imminent tax cuts, and there won’t be much left after that for offsetting massive public works projects.

Of course, infrastructure can also fall into the private domain, and there is much animated chatter about private-public cooperation to mitigate the impact of projects on the federal budget. But major infrastructure areas like roads and bridges, that are badly in need of upgrade, generally fall out of the purview of private money, because they do not offer commercially competitive returns. It is unclear how much practical infrastructure could realistically be funded from private investment sources.

Trumpism in the Age of Ryan

None of this is to say that the incoming administration will not have an impact on economic policy choices; by this point it should be clear to everyone that Donald Trump should not be underestimated. The President-elect knows his base; he understands what motivates the legions of voters in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan who turned up on Election Day for him. And he will have to show some love to this base. Nothing would render Trumpism a mere historical sideshow than a belief taking hold that their leader is a sell-out who will give the donors and DC elites the keys to the kingdom while they, the base, continue to get the short end of the stick.

To that end, optics will require the new economic policy to be perceived as something more than just the wholesale implementation of Paul Ryan’s narrow agenda of millionaire tax cuts and deregulation. But, as we noted in our commentary last week, the new team is likely to tread cautiously in its first months of occupying the White House. They will perhaps be more likely to find their red meat for the base in other areas – immigration and socio-cultural flashpoints, for example – and more or less let Ryan and Congress hash out and implement their economic agenda.

All of which is to say that, in our opinion, those investors who have been chasing up industrial metals prices and dumping intermediate bonds in these first days of the new order are likely chasing mirages.