Here’s a quote from a mainstream media fixture. How recent is it? “Financial markets have soared during the last month on expectations of a cut in rates. The Federal Reserve’s top officials…may have grown increasingly reluctant in the last several weeks to risk causing turmoil on Wall Street by leaving rates unchanged, analysts said.”

That little blurb from a New York Times article certainly sounds like it could have been written sometime within the past, oh, forty-eight hours. In fact, that article came out on July 7, 1995, two days after the Alan Greenspan Fed cut interest rates for the first time since 1992 (the article’s subtitle “Stocks and Bonds Soar” of course would be no less appropriate for anything written during the week ending June 21, 2019). The 1995 event was a particular flavor of monetary policy action called an “insurance cut,” and it has some instructive value for what might be going through the minds of the Powell Fed today.

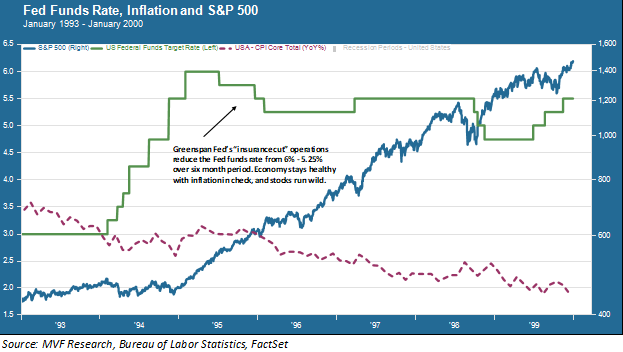

In the chart below we illustrate the context in which the 1995 rate (and two subsequent cuts ending in February 1996) took place. What we think of today as the “Roaring ‘90s” had not yet gotten into gear (in fact it was just about to start with the initial public offering of Netscape, the Internet browser, just one month after the Fed’s rate cut). In July 1995 the Fed had just capped off a series of seven rate hikes that had begun in 1994 and that had taken the stock market by surprise. Core inflation had crept back up above three percent, and a handful of economic indicators warned of a potential slowdown.

Despite the upturn in inflation, many observers at the time – on Wall Street, in corporate executive suites and in the Clinton White House alike – complained that the Fed’s rate hike program in 1994-95 had gone too far, too fast. Politics were certainly part of this mix, summer 1995 being a bit over a year away from the next presidential election (stop us if you’ve heard this one before). While the headline numbers didn’t suggest that a recession was imminent, there were indications that business investment had slowed with a build-up in inventories. The index of leading indicators, often used as a predictive signal for a downturn, had come in negative for four consecutive months. In announcing the rate cut, the Greenspan Fed emphasized that this move was more about getting out in front of any potential downturn, and less about the looming imminence of such a reversal.

Again, any of this sound familiar?

Equity investors, of course, would dearly love to imagine that a Fed insurance cut policy will always lead to the kind of outcome seen in the latter years of that chart above; namely, the stock market melt-up that roared through the late ‘90s and into the first couple months of the new millennium. Such an outcome is certainly possible. But before putting on one’s “party like it’s 1999” hat, it would be advisable to consider the differences between then and now.

The most glaring difference, in looking at the above charts, is the vast amount of blank space between the Fed funds rate and inflation. Yes, there was positive purchasing power for fixed income investors back in those days. Moreover, the US economy was able to grow, and grow quite nicely, with nominal interest rates in the mid/upper-single digits. This was real, organic economic growth. Yes – it’s easy to conflate the economic growth cycle of the late 1990s with the Internet bubble. But that bubble didn’t really take off until the very last part of the cycle – and in actual economic terms, Internet-related commerce was not a major contributor to total gross domestic product. This was a solid growth cycle.

The Greenspan insurance cuts, then, were undertaken with a fairly high degree of confidence in the economy’s underlying resilience. Today’s message is starkly different. What the market and the Fed apparently both conclude is that the present economic growth cycle cannot withstand the pressure of interest rates much or at all higher than the 2.5 percent upper bound where the Fed funds rate currently resides (and forget about positive purchasing power for anyone invested in high-grade fixed income securities). It’s a signal that, if the economy does turn negative, then central banks are going to have to get even more creative than they did back in the wake of the 2008 recession, because a rate cut policy from today’s already anemic levels won’t carry much firepower.

For the moment, the mentality among investors is optimistic that a best-of-all-possible-worlds result will come out of this. Dreams of a late-90s style melt-up are no doubt dancing in the heads of investors as they shovel $14.4 billion into global equity funds this week – the biggest inflow in 15 months. But no two bull markets are alike, and that goes for insurance-style rate cuts as well