There has been a decided thaw in the economic cold war between the US and China. Just last week, megatech chipmaker Nvidia, the first company to reach a $4 trillion market capitalization, got a boost to its already copious fortunes when the government lifted restrictions on its ability to sell its H20 chips to China. Those restrictions had previously forced the company into a $4.5 billion writedown from first quarter results.

More broadly, the lifting of export restrictions for Nvidia reflects a growing sense among investors that the bellicose rhetoric of several months ago is turning into a softer cadence of looking for dealmaking opportunities. That, in turn, is bringing back into play the question of China as an investable opportunity. Front and center in this debate is one of the year’s best-performing stock markets to date: Hong Kong.

The Window on China

Hong Kong’s role as a window on China – a proxy for those unwilling or unable to venture into the mainland itself – goes way, way back. Back to the days when multinational entrepots like Jardine Matheson and Swire’s – the historical inspirations for James Clavell’s saga “Tai Pan” – mediated between the pecuniary interests of foreign investors and the ever-changing faces of Chinese power from emperors to nationalists, red book-waving communists and Deng Xiaoping-era reformists.

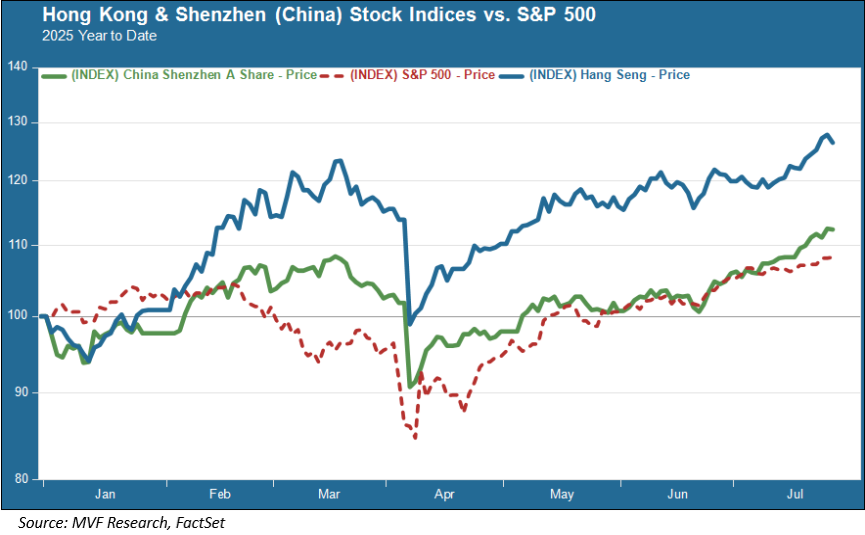

That storied history has taken a hit in recent years as the heavy political hand of Beijing weighed on the freewheeling ways of the Cantonese-speaking island. But there are definite signs of a resurgence, not least of all in the form of the Hang Seng stock index thus far in 2025.

Connecting to the Mainland

What’s behind the strong performance of Hong Kong this year, and why is it outpacing mainland Chinese equity indexes, represented in the above chart by the Shenzhen A Share index (green line)? To answer this, it is worth noting that Hong Kong serves as an opportunity for investors in mainland China – both institutions and individuals – to invest in Chinese companies while avoiding the tightly-controlled domestic financial system. They can do this via a mechanism called Stock Connect. Many of the most sought-after Chinese equity names – the likes of tech giants Alibaba and Baidu – are available in Hong Kong via Stock Connect but are not quoted on mainland exchanges.

This year, over $104 billion has been invested into Hong Kong from mainland sources, more than the amount invested over the entire year last year. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this has been happening as new listings by Chinese companies in Hong Kong are also at a record: 208 companies in the first six months of 2025, making Hong Kong the largest IPO market in the world so far this year, with $13.9 billion in deal flow compared to $9.2 billion on Nasdaq, $7.8 billion on the NYSE and less than half a billion in London.

Absent at the Feast

What is missing from this picture – or at least, what is not dominating the picture so far – is meaningful investment flows from origins other than China. This goes back to that question we introduced earlier: is China investable? There have been plenty of reasons for international investors to answer that question in the negative. The Chinese economy has been in the doldrums for years now, with the chronic sickness of its all-important property market and lackluster consumer spending that keeps the economy teetering on the brink of deflation.

But there are longer-term strategic reasons to question this hitherto conventional wisdom. China has a long term strategy predicated on achieving superiority in the so-called industries of tomorrow: artificial intelligence, clean energy and biotechnology, among others. China’s carmaking industry is now world class, particularly in the electric vehicle segment where it is the number one global producer. The fortunes of leading carmaker BYD are rising as those of Tesla are falling. The export-driven economy has managed to withstand the pain inflicted by the trade war – which, as noted above, appears to be softening.

Exposure to Hong Kong equities is not particularly difficult for international investors. Exchange-traded funds like the iShares MSCI Hong Kong ETF – or the MSCI Pacific ex-Japan variant if one wants some added diversification into other regional markets (Singapore, Australia and New Zealand alongside Hong Kong) – are liquid and cost-efficient. The risks are still there, of course. But as a long-term strategy, the China case study is not without merit. Hong Kong, in its time-honored role as a window on China – is a potentially attractive way to gain a foothold.