An up and down week on Wall Street may end on a slightly positive note, if the sentiment we are seeing on this Friday morning makes it through the afternoon. Don’t mistake this for some kind of definitive trend, though – what’s been happening this week is much more about technical buy and sell triggers that send much of the market’s intraday volume hither and yon. At one point earlier this week the S&P 500 actually closed below its 200-day moving average for the first time since early 2016. There’s nothing magical about moving averages, of course, except that lots and lots of trading strategies are programmed to react to them. Perception is reality in the world of short term trading.

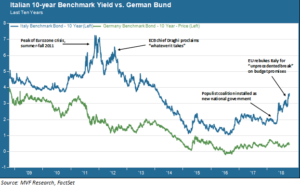

In any event, while indexes bounce up and down in search of a driving theme to provide direction for the rest of the year (which we think has a better chance of being up but a not immaterial chance of being down) we want to dig into some of the X-factors contributing to the current frisson of unease. In this week’s commentary we feature the Italian debt market. Spreads between Italian benchmark bonds and German Bunds (the go-to safe haven for EU fixed income) are at their widest levels in four years.

Return of Eurozone Mal de Mer

The above chart shows that Italy-Bund spreads are a useful indicator of unrest in the Eurozone. After ECB chief Mario Draghi assured the world that the Eurozone would stay intact with his “whatever it takes” speech in 2012, the spread tightened from the wide gulf of the crisis years to a more typical risk premium that lasted for most of the past four years. That all changed with the national elections in March 2018, which ended with a populist government sworn in two months later, in May. The coalition government of the Five Star Movement (FSM) and the League, representing different flavors of anti-establishment populism, set out some ambitious plans to deliver on its campaign promises of stimulus measures for growth and jobs. Eventually, these plans found their way into a budget the country is required to submit to EU officials in Brussels, to ensure that the terms are in keeping with EU standards and constraints. Brussels, to put it mildly, was not amused.

Roman Rebuke

EU economics officials routinely issue rebukes to member country policies which they see as deviating from rules – particularly the rules developed during the crisis years earlier this decade. But the language in this Thursday’s communique from Brussels to Italian finance minister Giovanni Tria was – well, practically Trumpian in its histrionic flavor. “Unprecedented in the history” of EU budget rules! – said the stern technocrats. One would think nothing of such a seismic nature had rocked the continent since Charlemagne crushed the Merovingians.

The odd thing is that Brussels’ main sticking point with the budget is its assumption of running a 2.4 percent fiscal deficit. While not inconsiderable, that is a lower fiscal deficit than those run by EU members France and Spain, and it is also lower than what the new Italian government initially planned after the coalition came together in May. The real underlying problem is that few observers believe a fiscal deficit of this size is sustainable for a country challenged by slow economic growth and a cost of debt that is already rising. The bond investors who have been selling off Italian bonds this week anticipate further downgrades to Italian debt from S&P and Moody’s later this month, and expect further headwinds to buffet the fragile condition of large Italian banks.

Populist-Technocrat Smackdown

The bigger contextual picture, of course, goes beyond Italian sovereign debt to the overall health of the EU. There has been little in the way of good news from Europe this year. The Brexit negotiations are an ongoing fiasco painting nobody in a good light. On the eastern periphery Hungary and Poland can fairly be called ex-democracies as their authoritarian governments consolidate one party rule. Italy and Austria are ruled by populists. Establishment darling Emmanuel Macron’s approval ratings in France are an abysmal 33 percent (that’s lower than Trump has ever fallen here back home!). And Germany is also teetering on the dividing edge between populists and technocrats. Witness this past weekend’s regional elections in Bavaria where the long-dominant CSU (the regional partner of Chancellor Merkel’s ruling CDU) suffered its biggest loss of seats in the party’s postwar history.

In this fraught landscape, the notion of a fiscal crisis or banking system collapse in Italy has the potential to inflict more damage than the original Greek economic crisis that led to the dolorous years of 2011-12. Back then those three magic words uttered by ECB chair Draghi – whatever it takes – were enough. We may see proof in the coming weeks, one way or another, whether indeed it is enough.